Symposiumsbericht: Art and/or Politics

There is a moment during the video piece "Die Kleine Bushaltestelle (Gerüstbau)" (2007/2010)

when Isa Genzken makes the observation that political artists, or as she

describes them, “artists who want to show the miseries of the world”, often

make art that is aesthetically miserable. The question of how much (if at all)

artists should sacrifice formal concerns in the service of political activism

has gained renewed importance of late and as a result conferences on art and

politics seem to have been springing up in cities across the world. "ART and/or politics, or: How political

may/must art be (today)?", a two-hour long panel discussion featuring Monica

Bonvicini, Adam Broomberg, Thomas Demand, Peter Geimer, Philipp Ruch and Beat

Wyss, started with moderator Michael Diers showing a number of slides of

political art works: David Young’s highly aesthetic photographs of G-20

demonstrators being hit with water cannons, "Open

Casket" (2016), Dana Schutz’s painting of murdered black teenager Emmett

Till and Sam Durant’s "Scaffold" (2012),

a sculpture which draws on the gallows used for the mass execution of 38 Dakota

Indians in 1862. The latter two works have been mired with controversy after

protests erupted in response to their display at the Whitney Biennial and The

Walker Art Centre respectively. The inclusion of these images didn’t just serve

to give the six participants a common starting point for the discussion, but

also added another focus beyond the question of artistic autonomy. Namely, do

artists have the right to use the (tragic) histories of others in their own

(political) work?

The artists Thomas Demand and Monica Bonvicini showed some

sympathy for Schutz and Durant, with Bonvicini pointing out that Durant had

been working consistently with these themes for over 10 years (such as in his

2005 exhibition "Proposal for White and

Indian Dead Monument Transpositions", Washington D.C.) and Demand musing

that: “You want to do justice to the original [Schutz’ painting is drawn from

photographs of Till’s mutilated body]. Did she? You could argue that she did.” As

talk turned away from these controversies to the panellist’s own practices,

Demand, who is best known for his paper reconstructions of

historically-relevant media images, stressed that the role of art is to

communicate but insisted that it wasn’t compulsory to be political as an

artist. Adding: “The bus driver doesn’t have to know our views on everything”.

When asked by Diers whether his art was political, he seemed reluctant to view

his works only through this lens and answered, “It’s a condition, but I

wouldn’t want to reduce it to that.”

Monica Bonvicini also expressed frustrations about the expectations put on artists to be political. She spoke at length about the problems with the biennial format, where curators can expect artists to make a critical statement about the city or country after spending only a few days there. Her complaint that “You put out a banner and then you go home” was an especially interesting choice of words considering that another panellist, Philipp Ruch, had done just that during a political intervention in front of the German Chancellery recently. As a part of the Berlin-based art collective Zentrum für politische Schönheit (Center for Political Beauty), Ruch organised an installation featuring a black Mercedes next to a banner with the faces of Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Vladimir Putin and Saudi Arabia’s King Salman bin Abdulaziz, with the words “Do you want this car? Kill dictatorship.” The same week, the group also held a leaflet drop in Istanbul’s Gezi Park, where the text urged readers to “Defend the democracy. Fight against Racism. Bring the dictatorship down.” Ruch’s position ignited some criticism from the art historians Peter Geimer and Beat Wyss, with them objecting to his interest in actions that merge the categories of art and politics. While for Ruch, “That’s the most important thing… when art and politics come out of their boxes,” Geimer expressed his concern that art not only loses its specificity when viewed in this way, but that Ruch as an artist/politician operates from a ‘comfortable’ position, because he can hide behind either shield depending on the context.

With all of the participants bar Philipp Ruch remaining cagey (some might say realistic) about art’s potential for political change, Diers noted the rather downbeat tone of the discussions and asked towards the end of the afternoon, “Could it be that as artists, critics and art historians we’re not in the camp of wanting to change the world?” Perhaps determined to finish on a positive note, Adam Broomberg chose to tell the story of his art professor bringing his attention to sculptures that were being built by the communities in the townships across Apartheid-era South Africa. In order for the state to control these environments, they had built 120-foot lights in the townships and cleared of rocks and anything else that could be used as weapons, but these modernist-looking sculptures turned out to be armaments, “There was no concrete so people would just grab a brick and it was arms”. In this case art was a direct and unmediated tool for political change, which was desperately needed. An intervention that gave Broomberg “a kind of optimism that I’m still living with.” (Chloe Stead)

Symposium: O Superman

Symposium: O Superman

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

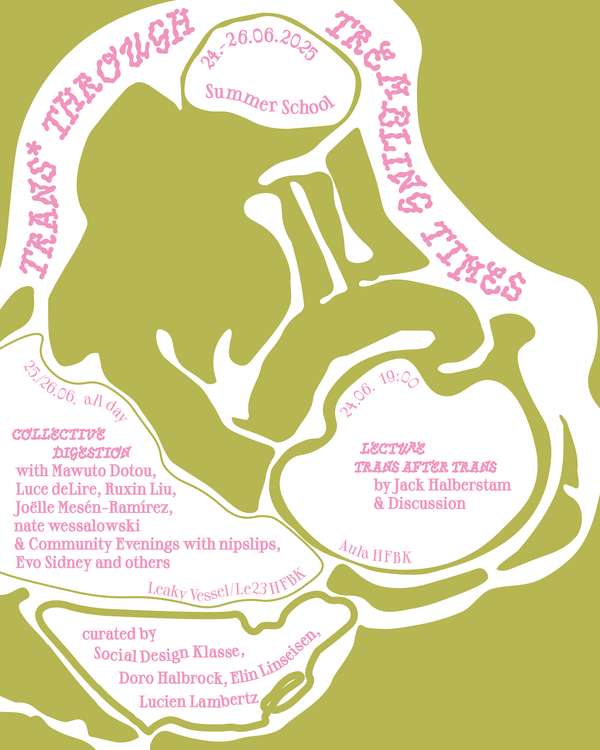

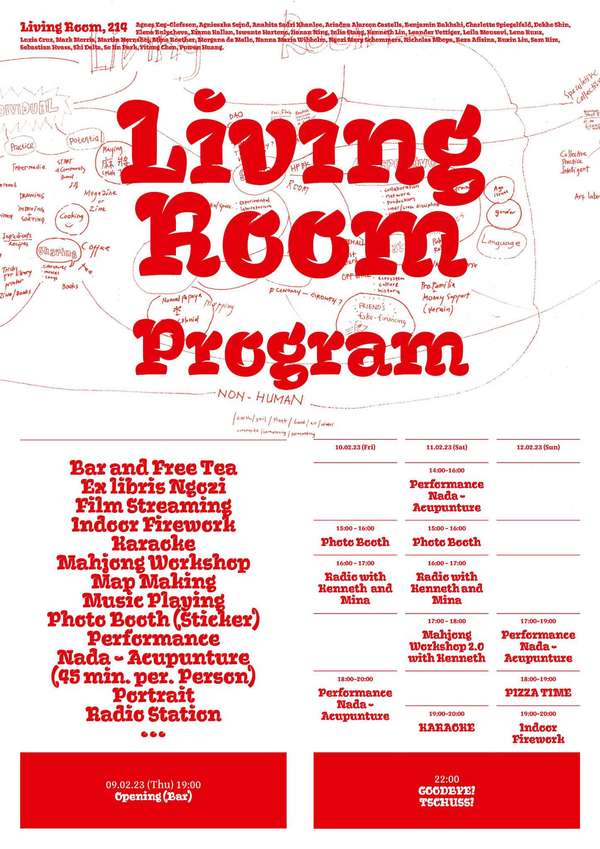

Lange Tage, viel Programm

Lange Tage, viel Programm

Cine*Ami*es

Cine*Ami*es

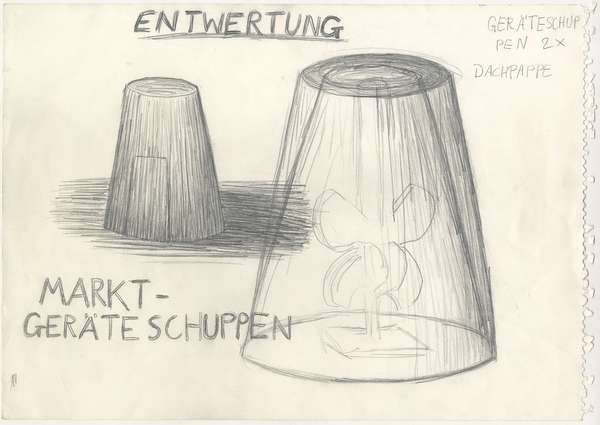

Redesign Democracy – Wettbewerb zur Wahlurne der demokratischen Zukunft

Redesign Democracy – Wettbewerb zur Wahlurne der demokratischen Zukunft

Kunst im öffentlichen Raum

Kunst im öffentlichen Raum

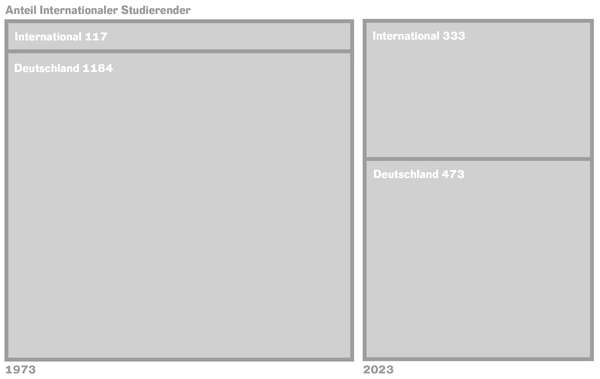

How to apply: Studium an der HFBK Hamburg

How to apply: Studium an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2025 an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2025 an der HFBK Hamburg

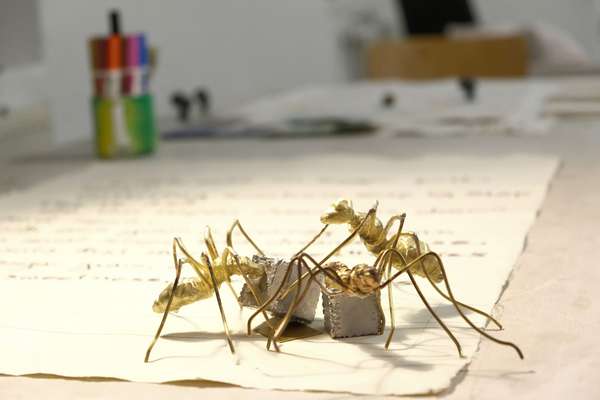

Der Elefant im Raum – Skulptur heute

Der Elefant im Raum – Skulptur heute

Hiscox Kunstpreis 2024

Hiscox Kunstpreis 2024

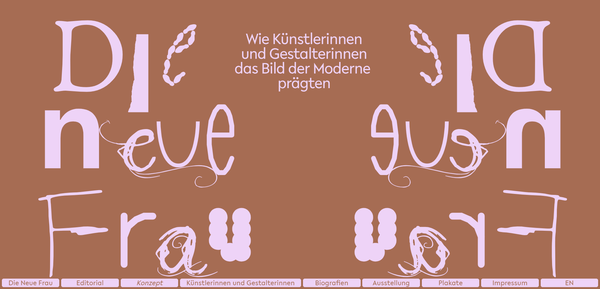

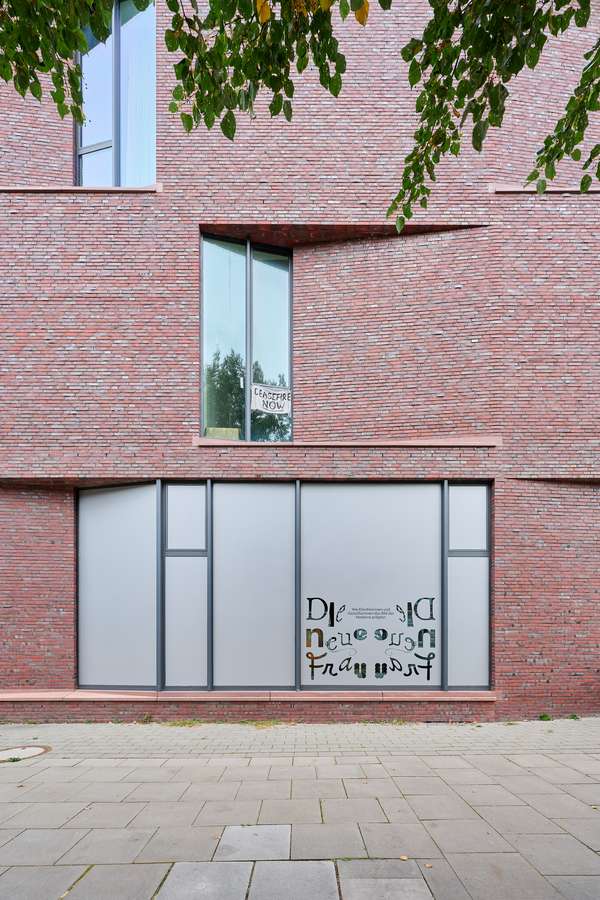

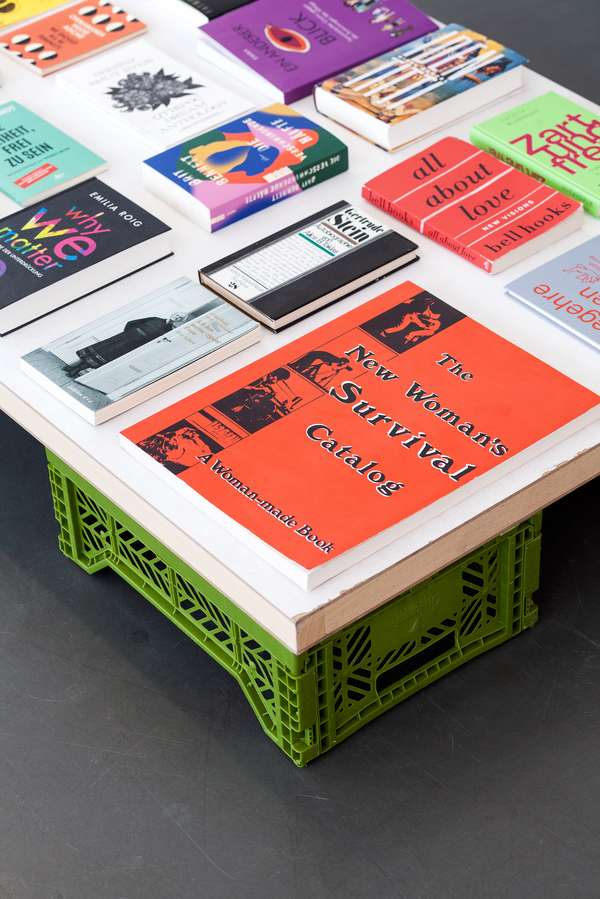

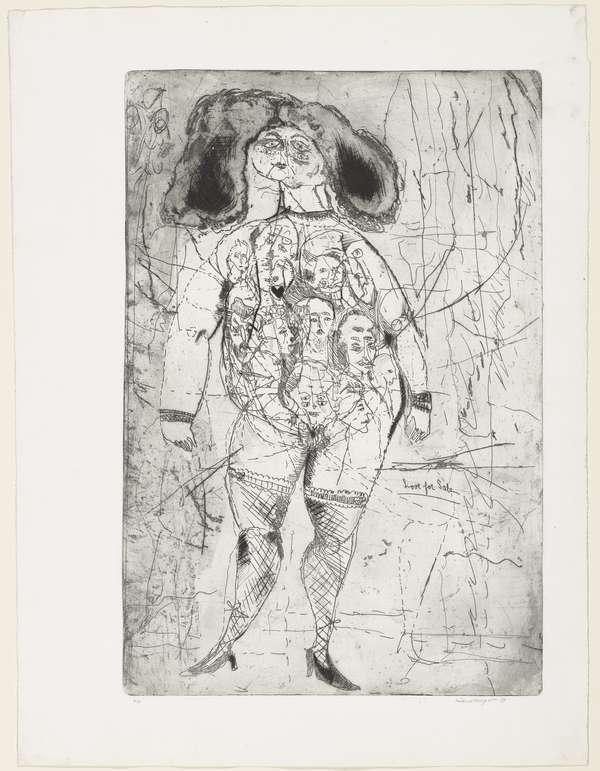

Die Neue Frau

Die Neue Frau

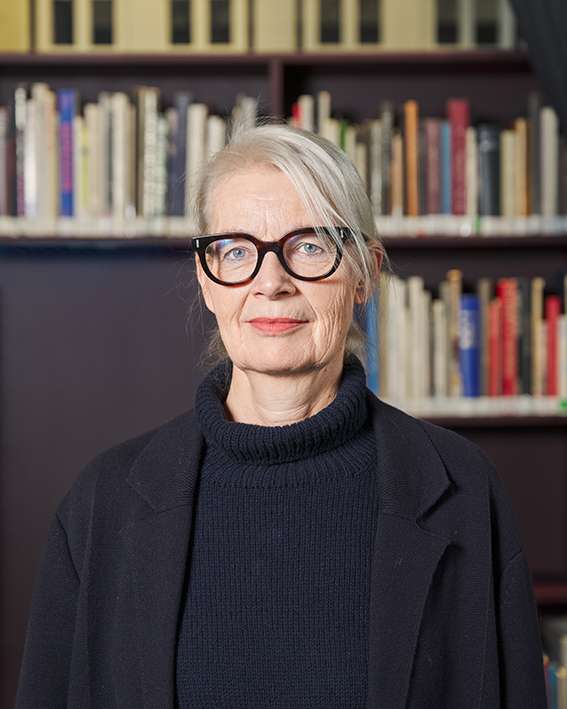

Promovieren an der HFBK Hamburg

Promovieren an der HFBK Hamburg

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Finkenwerder Kunstpreis 2024

Finkenwerder Kunstpreis 2024

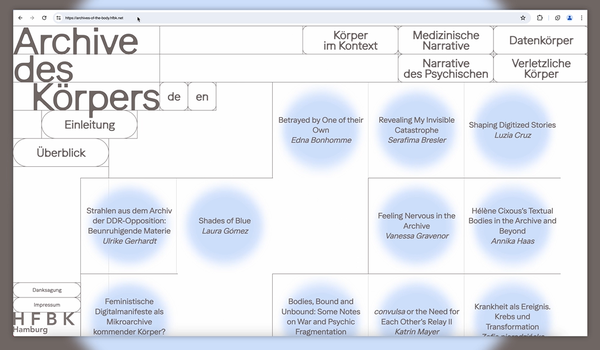

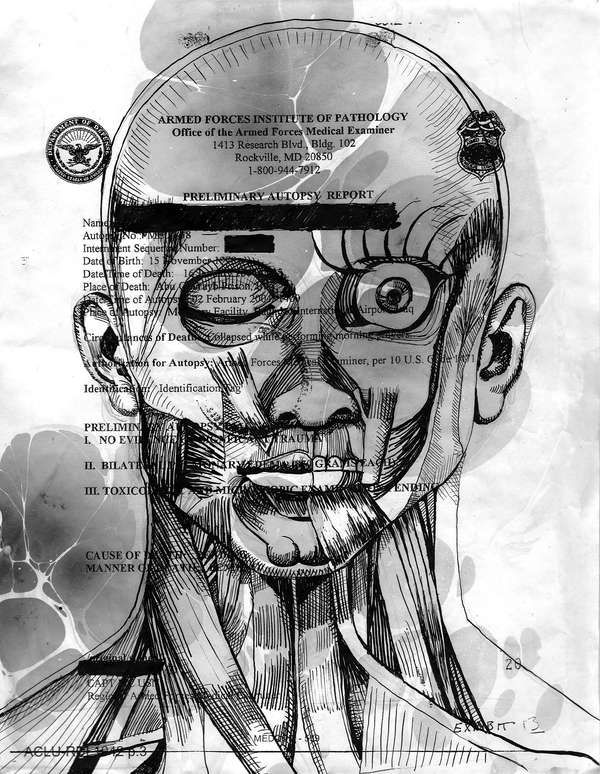

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

Neue Partnerschaft mit der School of Arts der University of Haifa

Neue Partnerschaft mit der School of Arts der University of Haifa

Jahresausstellung 2024 an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2024 an der HFBK Hamburg

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

Extended Libraries

Extended Libraries

And Still I Rise

And Still I Rise

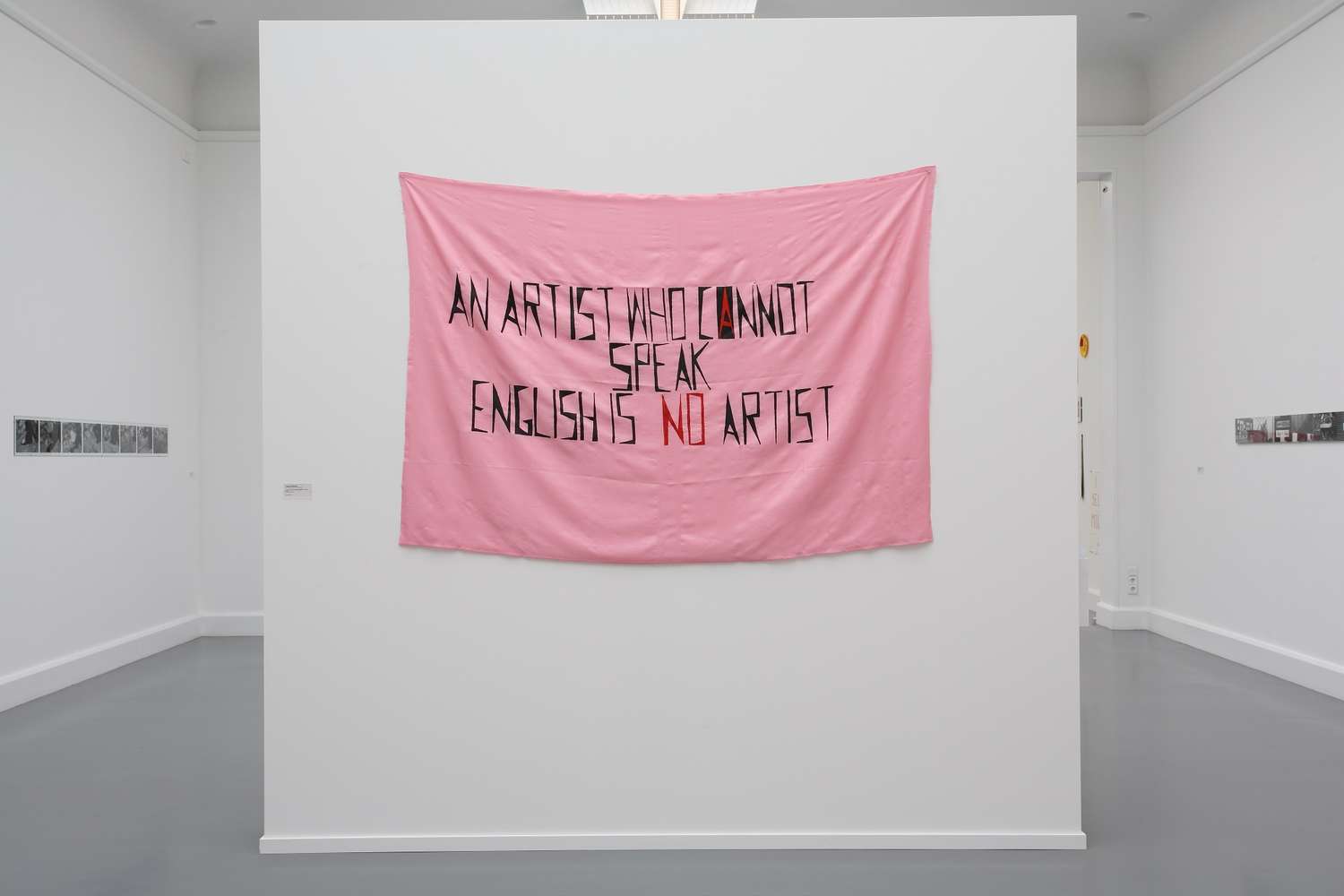

Let's talk about language

Let's talk about language

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

Let`s work together

Let`s work together

Jahresausstellung 2023 an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2023 an der HFBK Hamburg

Symposium: Kontroverse documenta fifteen

Symposium: Kontroverse documenta fifteen

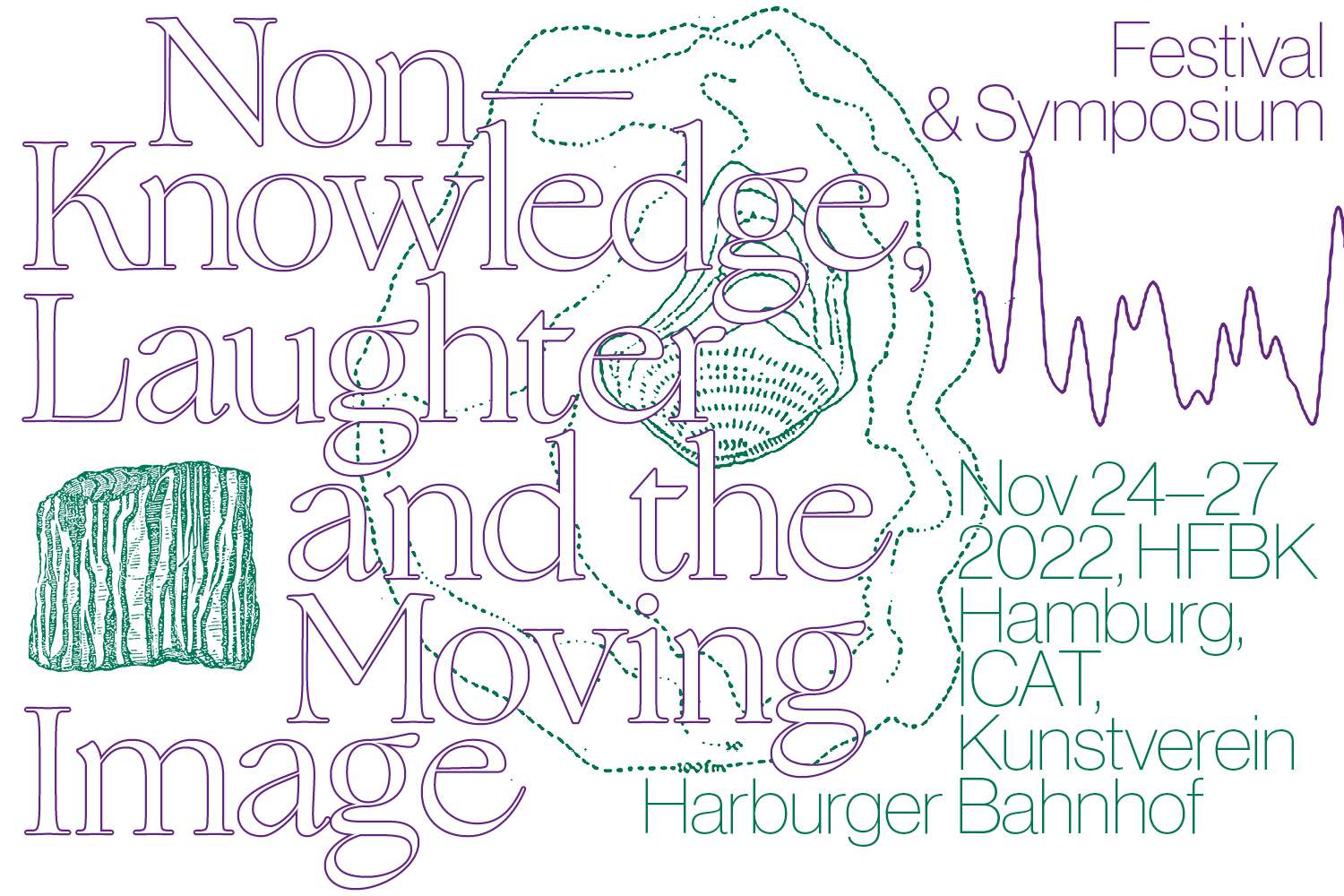

Festival und Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

Festival und Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

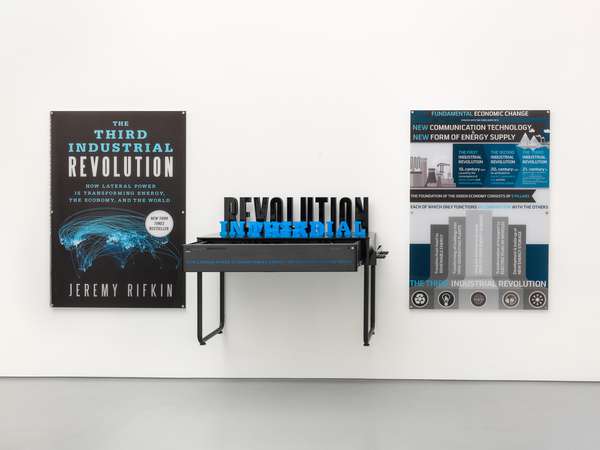

Einzelausstellung von Konstantin Grcic

Einzelausstellung von Konstantin Grcic

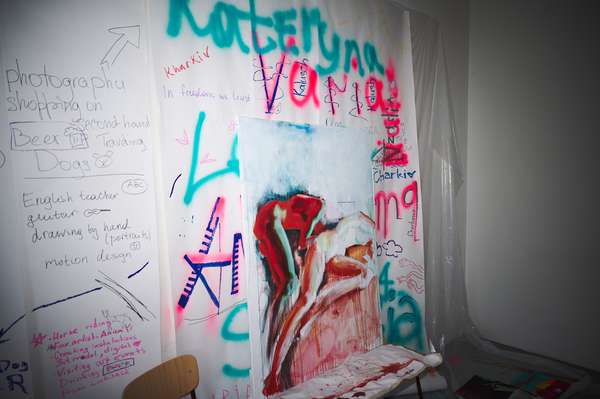

Kunst und Krieg

Kunst und Krieg

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

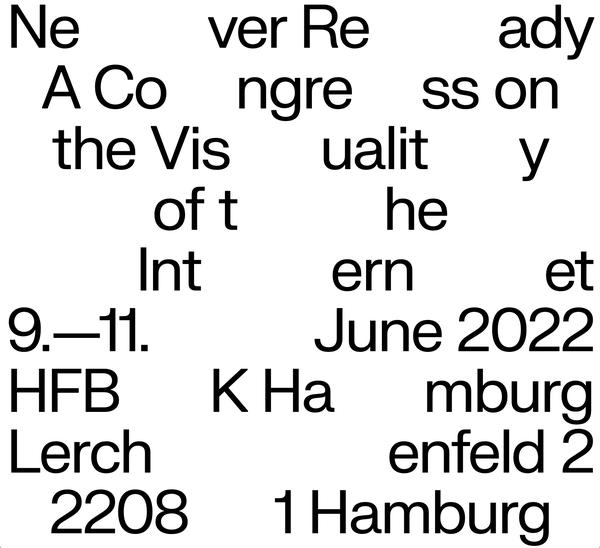

Der Juni lockt mit Kunst und Theorie

Der Juni lockt mit Kunst und Theorie

Finkenwerder Kunstpreis 2022

Finkenwerder Kunstpreis 2022

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Raum für die Kunst

Raum für die Kunst

Jahresausstellung 2022 an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2022 an der HFBK Hamburg

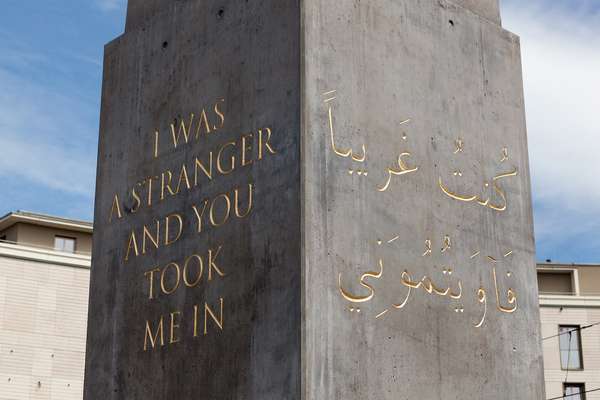

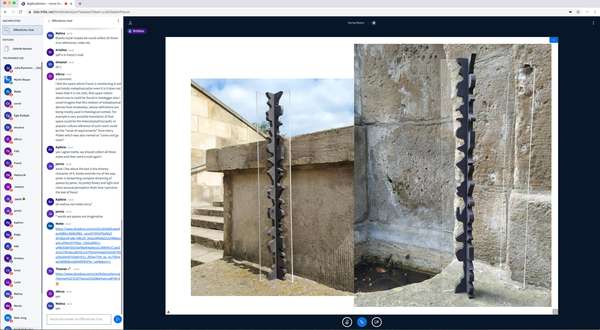

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments

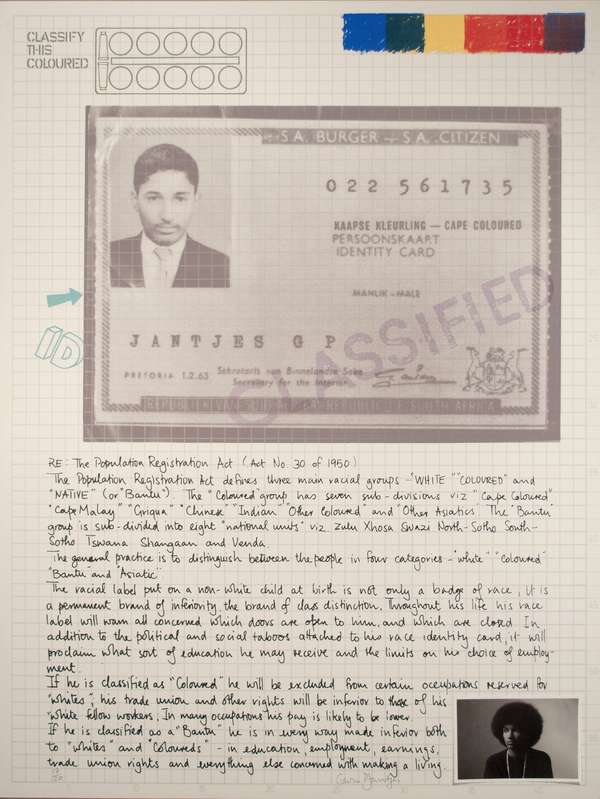

Diversity

Diversity

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

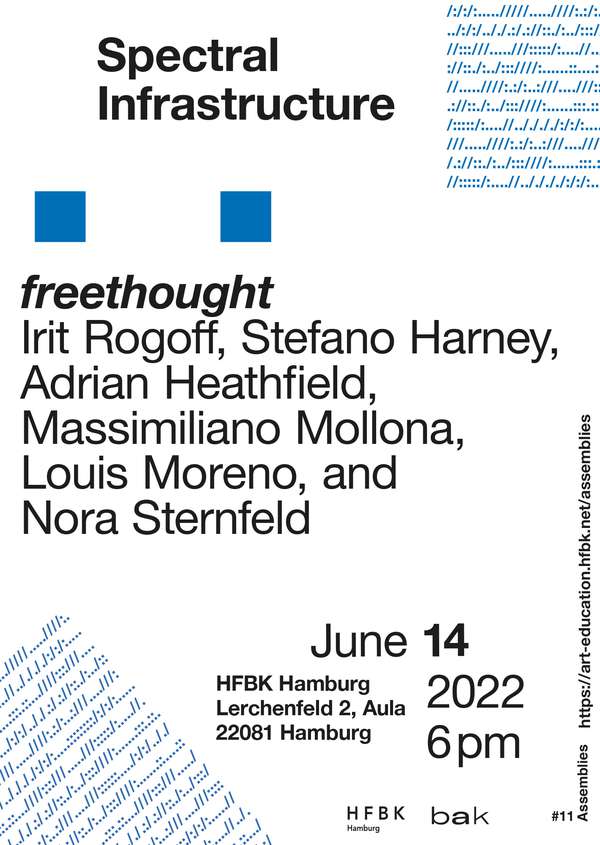

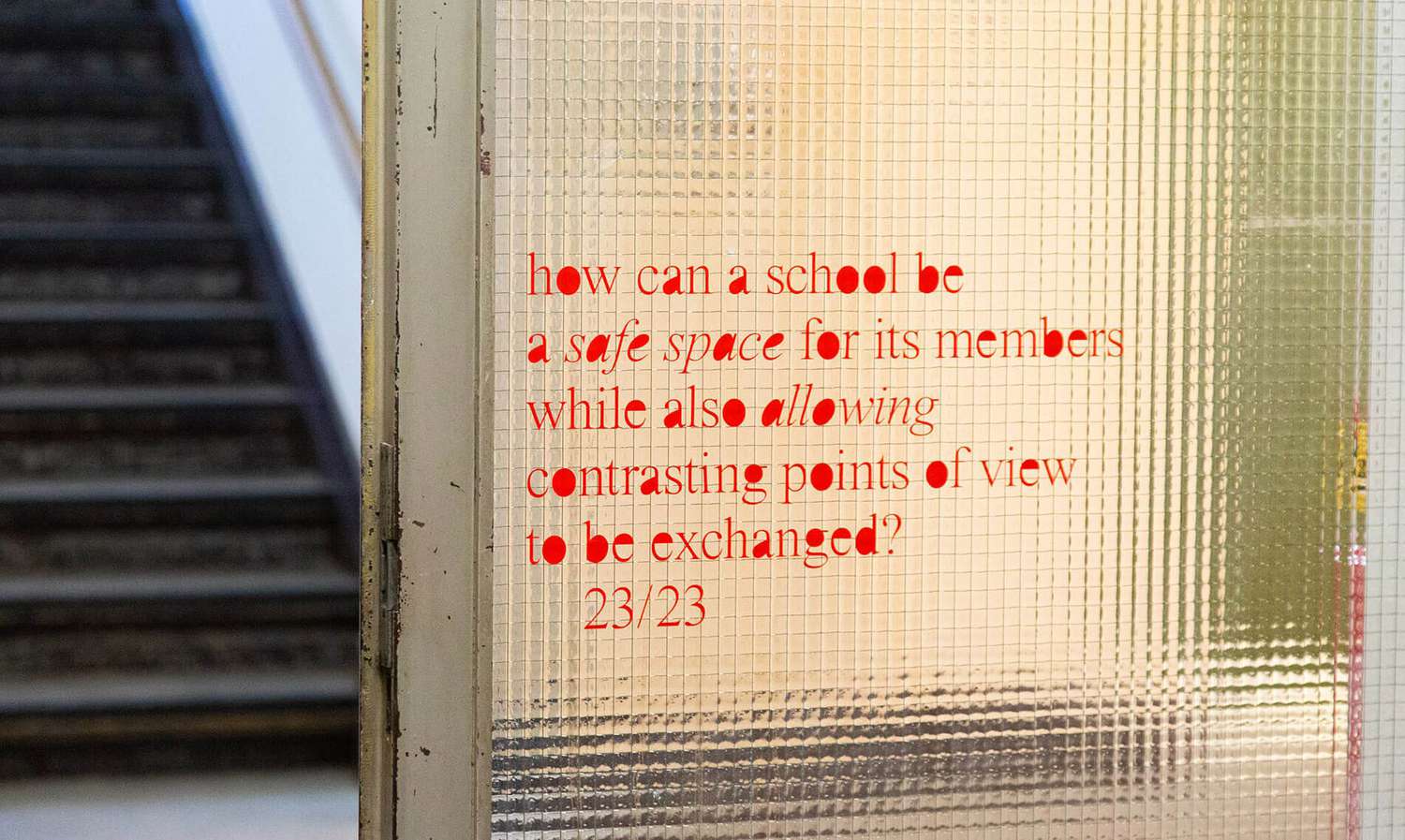

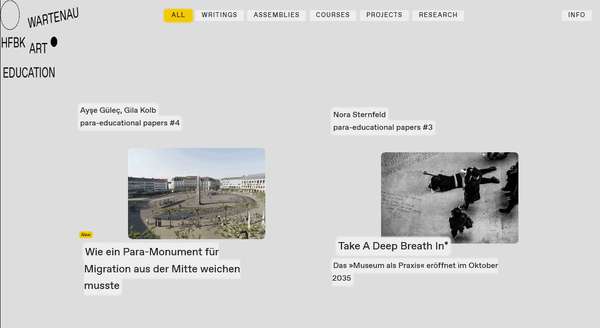

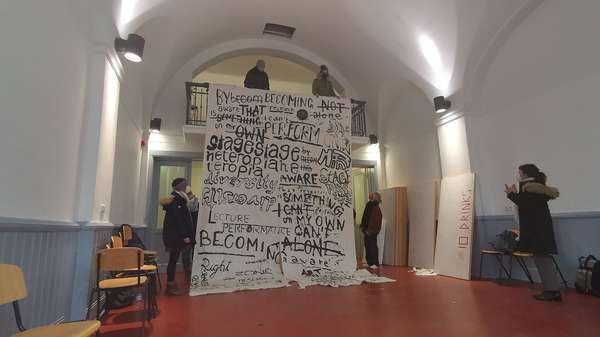

Vermitteln und Verlernen: Wartenau Versammlungen

Vermitteln und Verlernen: Wartenau Versammlungen

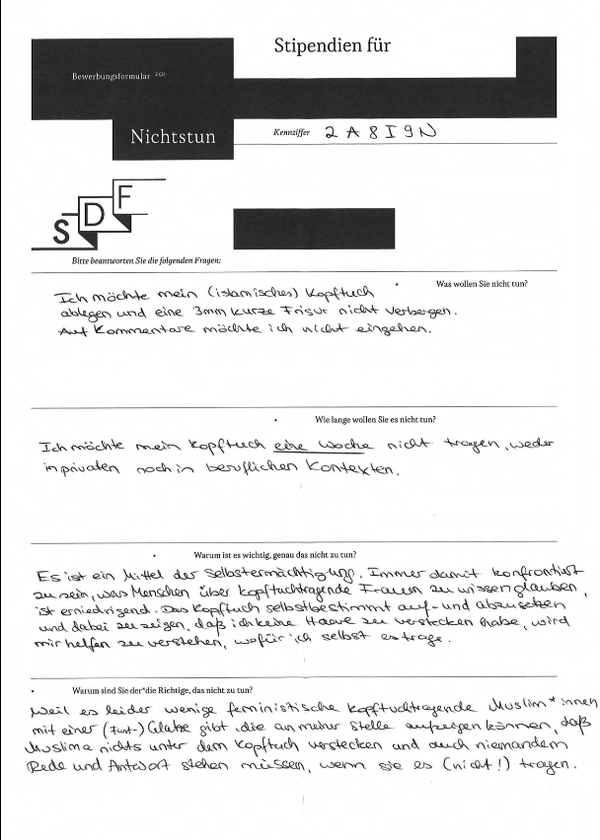

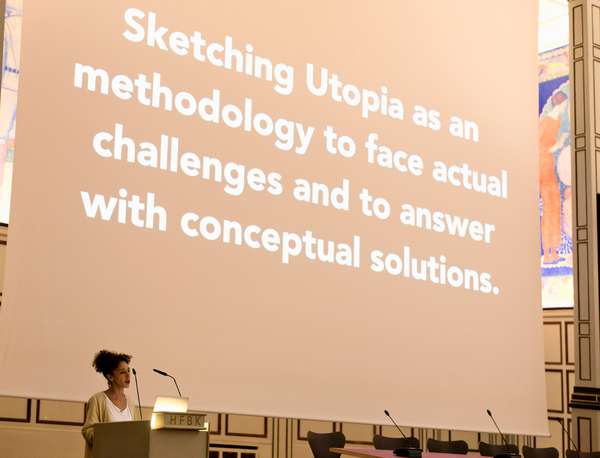

Schule der Folgenlosigkeit

Schule der Folgenlosigkeit

Jahresausstellung 2021 der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2021 der HFBK Hamburg

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

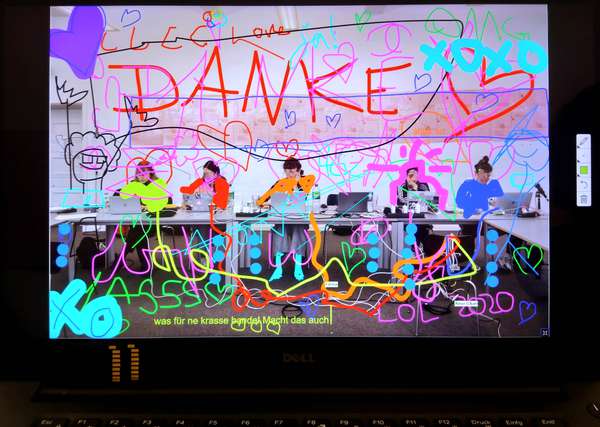

Digitale Lehre an der HFBK

Digitale Lehre an der HFBK

Absolvent*innenstudie der HFBK

Absolvent*innenstudie der HFBK

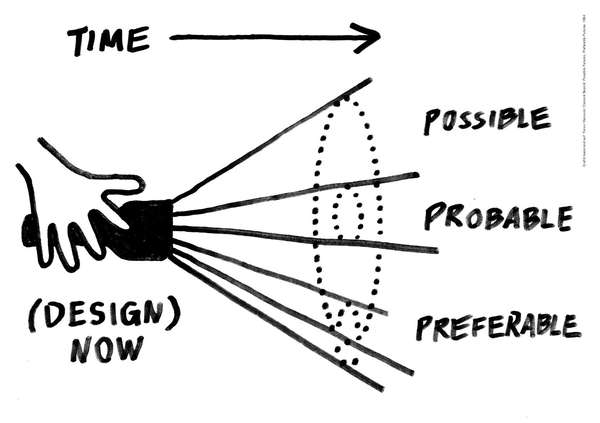

Wie politisch ist Social Design?

Wie politisch ist Social Design?