Assembling/Disassembling the Curriculum

How diverse is the curriculum of the HFBK Hamburg? This was the question behind an intervention by the student group 3RD-SPACE for the HFBK lecture timetable in the summer semester of 2021. Our author not only talked to the group, but also posed this question to HFBK professors.

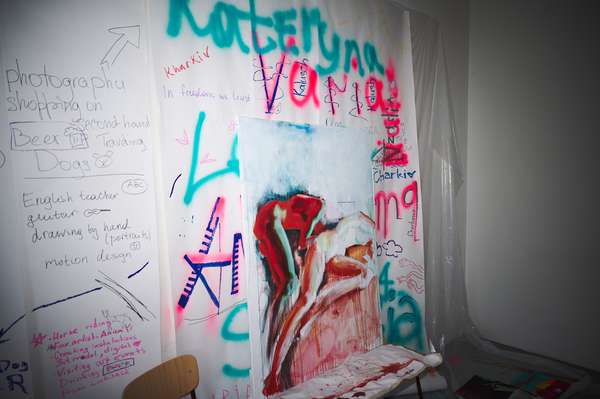

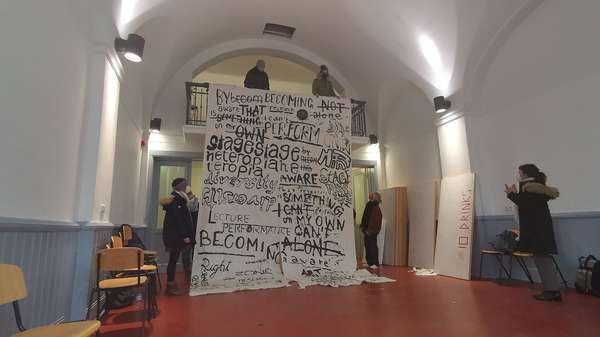

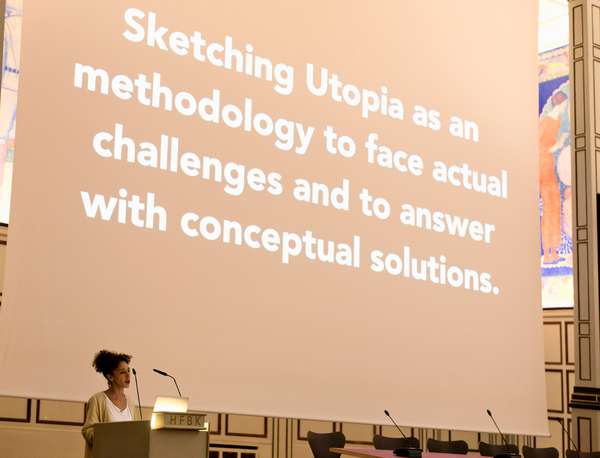

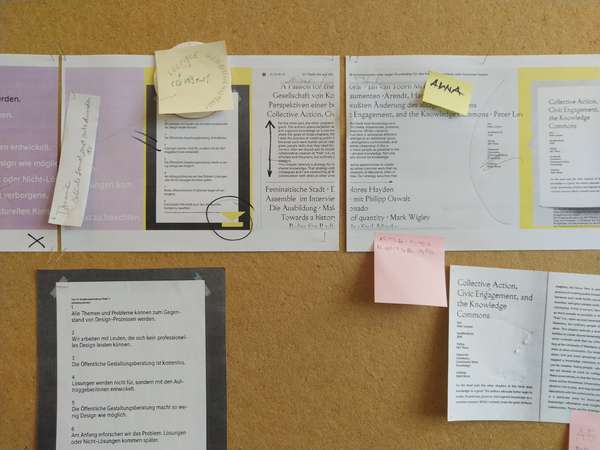

In April 2021, the HFBK Hamburg members received an e-mail from 3RD-SPACE, a student-organized negotiation space, with a special version of the lecture timetable (Vorlesungsverzeichnis). 3RD-SPACE created an alternative curriculum similar to the one the HFBK administration sends out each semester, with a more diverse, inclusive, and participative learning program. The group explains their motivation behind the intervention as “a demand for diverse, Eurodecentric teaching and learning opportunities to decentralize structures and content, as well as to present students’ aspirations for knowledge production and transmission from a plurality of perspectives.”

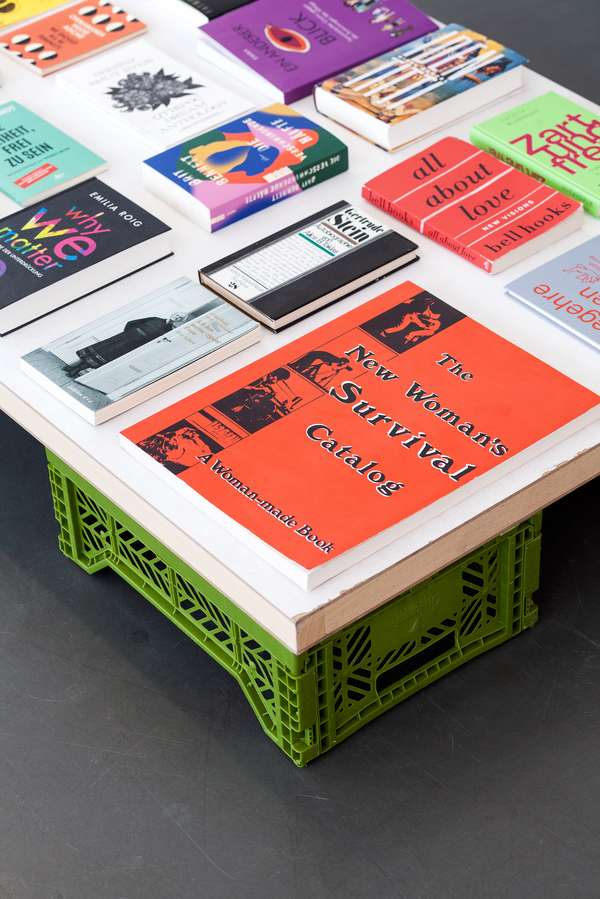

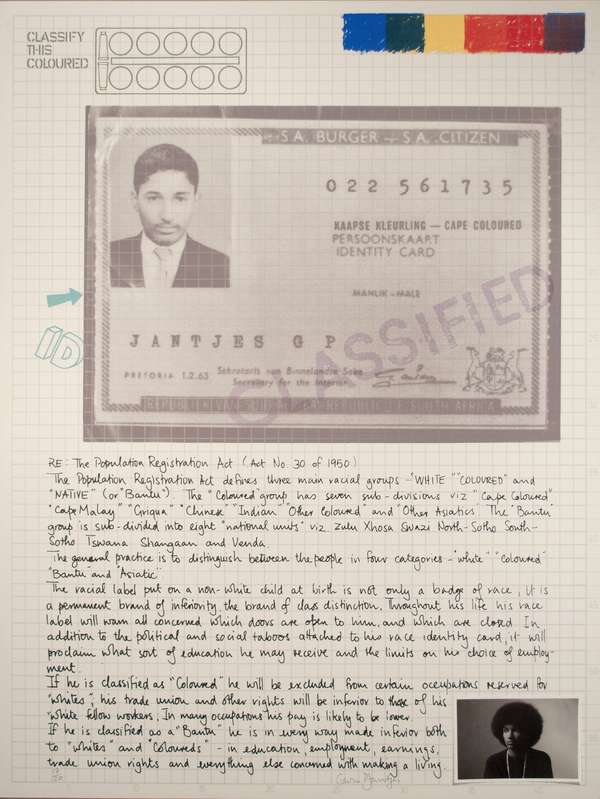

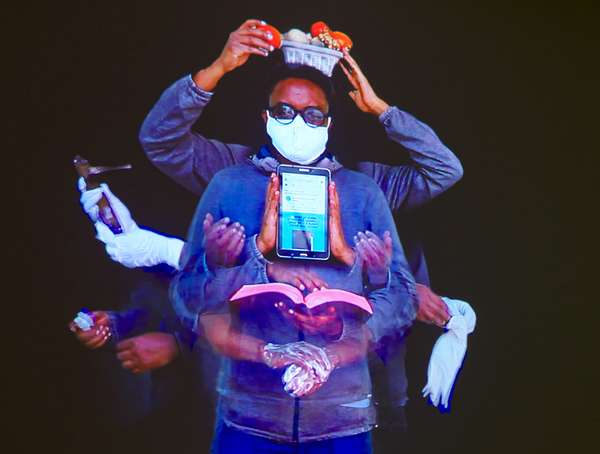

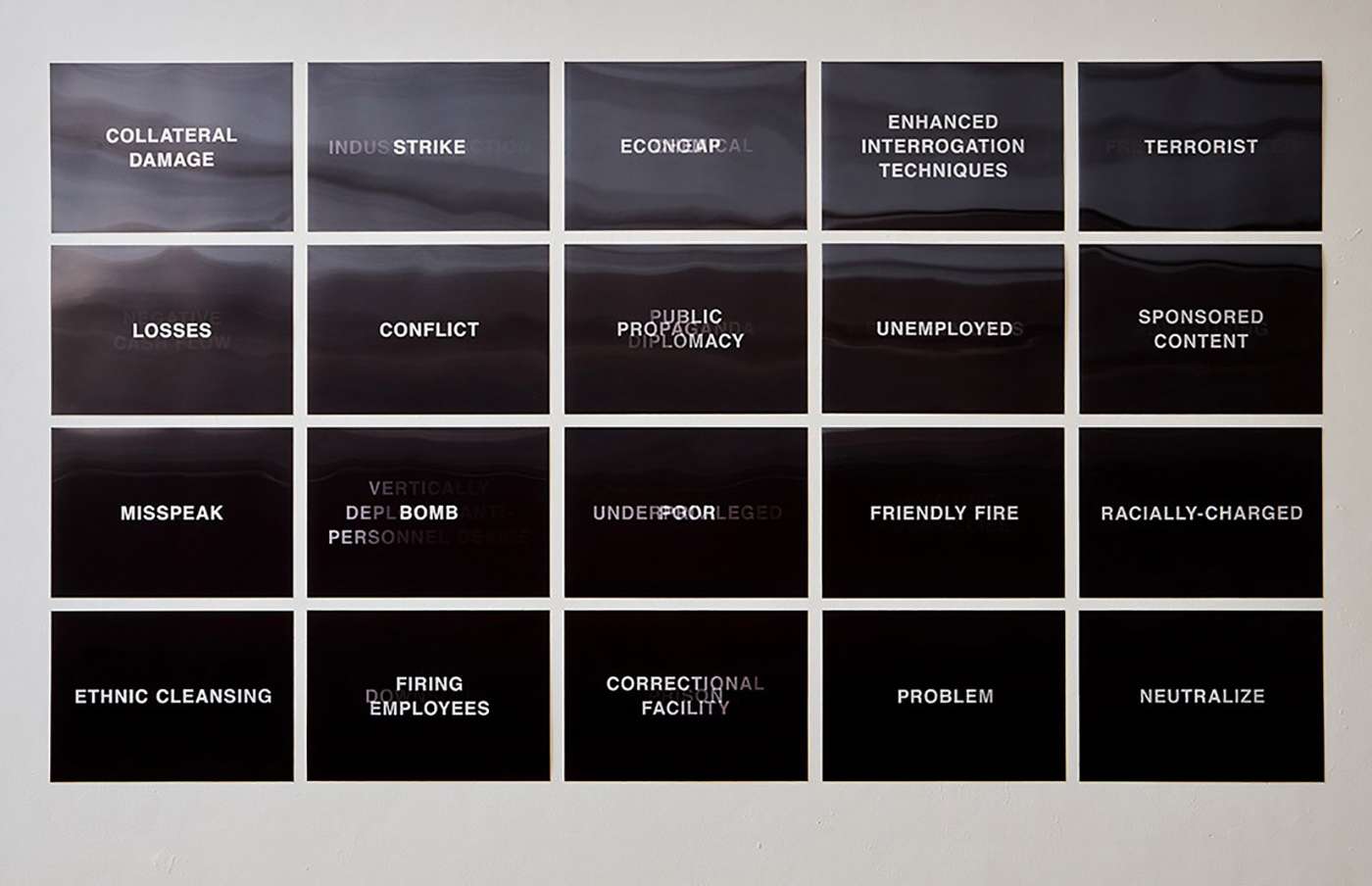

The suggested curriculum included BIPOC design history, non-Eurocentric art movements such as Afrofuturism, critical examination of racism in film production, and political and social conflicts in indigenous contexts, among other topics. Complementary to the history of Western art, seminars focusing on diverse narratives such as the Russian contemporary art scene and the role of émigré cultures in design and architecture aim to expand the canon. Workshops on open expression, anti-discrimination, and the possibilities of spaces for people with special needs strengthen the practice through collaboration.

“Diversity of positions is essential in our debating chamber. We see opposition and confrontation as valuable catalysts for the emergence of new spaces,” says 3RD-SPACE. The group invites anyone interested to join the discussion to work on questions relating to teaching and learning methods, as well as the diversification and decentralization of these structures. “The problem is not that there is something missing in the curriculum that has to be filled in order to be complete. The curriculum reflects the position of the institution itself; it is part of a colonial, racist, discriminatory education bureaucracy, which has as its aim the quantification, regulation, and alignment of our lives in terms of time and space. Through the lecture timetable, we could reflect on the position of the HFBK Hamburg and its involvement in deconstructing colonial and discriminatory structures,” says the group, underscoring the urgency of the matter.

3RD-SPACE has further structural demands to enhance diverse perspectives: transparency in financial management, the selection of professorships and courses, and the right of students to take an active role in decision making. The group also notes that student projects should be able to get funds from the university without a need to justify themselves to a jury, such as the Freundeskreis. And, last but not least, they ask for recognition of the already existing diversity at the HFBK Hamburg in the multilingual, diasporic student body, as well as the knowledge and capability of the staff taking care of the building, as opposed to the mainly German- or English-speaking administration and teaching faculty.

Besides student voices, how does the teaching faculty reflects on the existing curriculum and diversity at the HFBK Hamburg and identifies what is missing? I addressed this question to some professors from different departments.

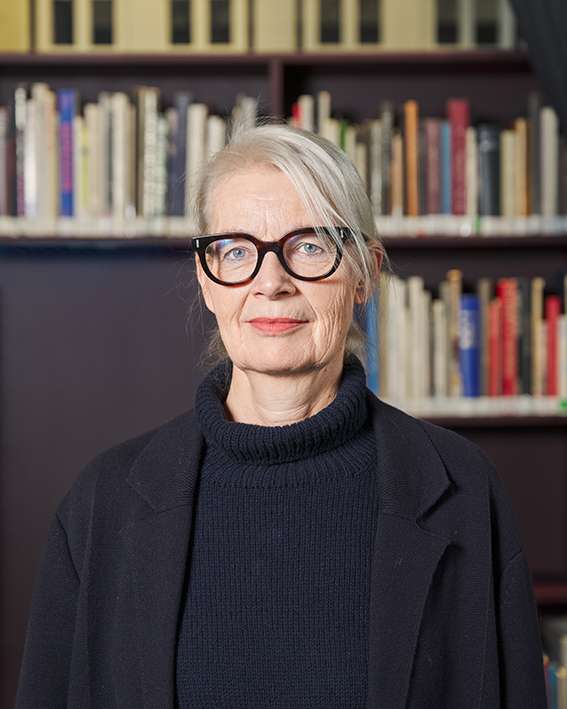

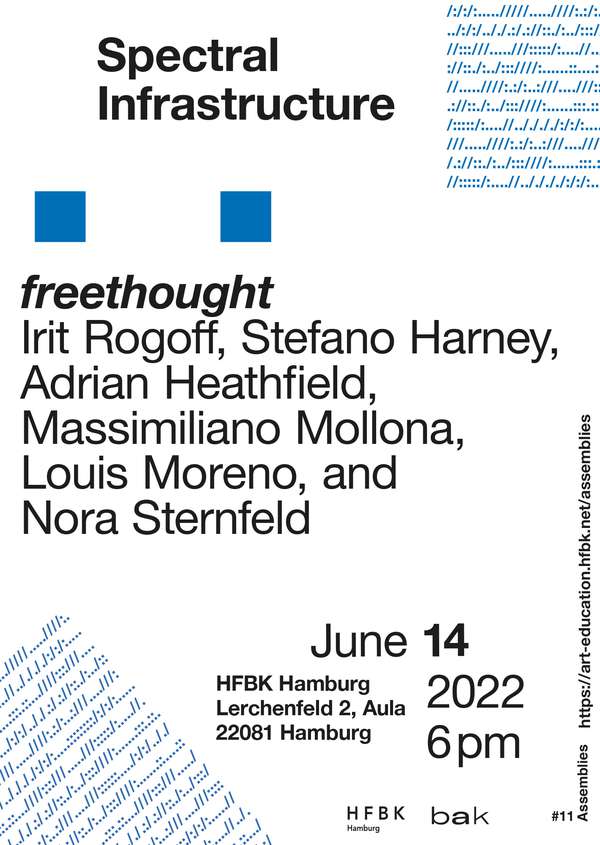

Dr. Nora Sternfeld, Professor of Art Education

When I think about diversity in relation to a lecture program, I think about the need to learn from different lines of thought and different positions. I think of a good art school as a place which resonates within and through the artistic and intellectual differences that are discussed and expressed there. When I think about diversity in relation to the existing exclusions and inequalities, I’m not sure if I’m satisfied. I would rather propose to talk about these inequalities and exclusions, about their structural dimensions (and about the need for structural change in society and in the school), about equality and solidarity, about social struggles, alternatives, and counter-canons. I think that the HFBK Hamburg is a place where this can happen. And I’m personally looking forward to working with colleagues, students, artists, educators, and researchers to imagine this school and to work toward it together.

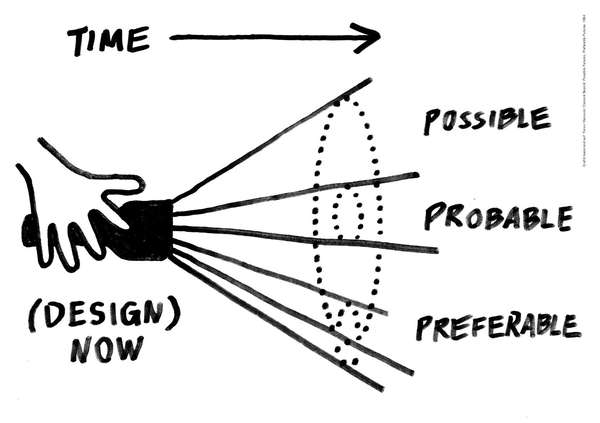

Jesko Fezer, Professor of Experimental Design

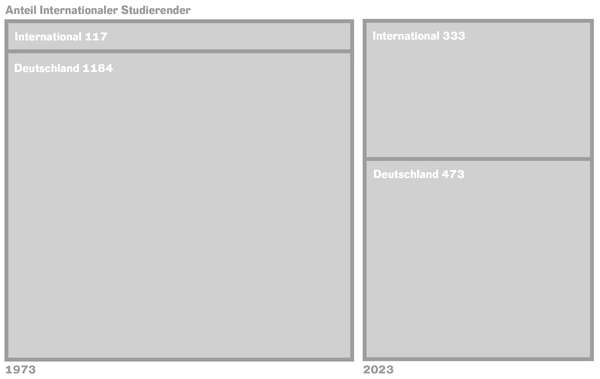

Indeed, one could say that the HFBK Hamburg is quite diverse. But in relation to what? In relation to the design profession, to other universities, to a kindergarten, a factory, or a supermarket? Despite all efforts, the institution obviously does not represent the diversity of society out there. Probably no art school has ever adequately represented society. Art schools are by definition exclusive spaces. I think we could get a better understanding of their exclusivity if we look at the diversity of the cities surrounding our academic islands. In particular, the barriers to access for people with different migration backgrounds (which in Hamburg mostly refer to Turkey, followed by Poland, Afghanistan, Syria, and Russia) as well as from working-class households or with a non-academic educational background should be given greater consideration. How can we make our school more porous?

Annika Larsson, Professor of Introduction to Artistic Working Methods

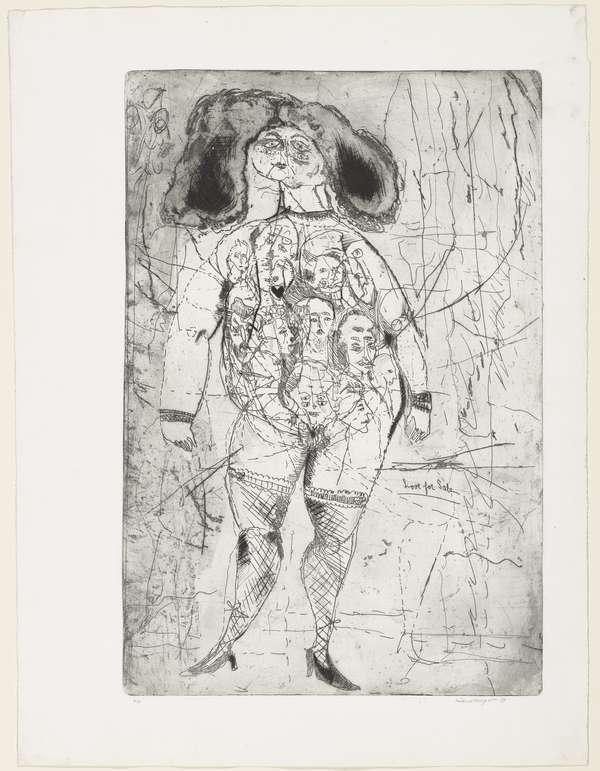

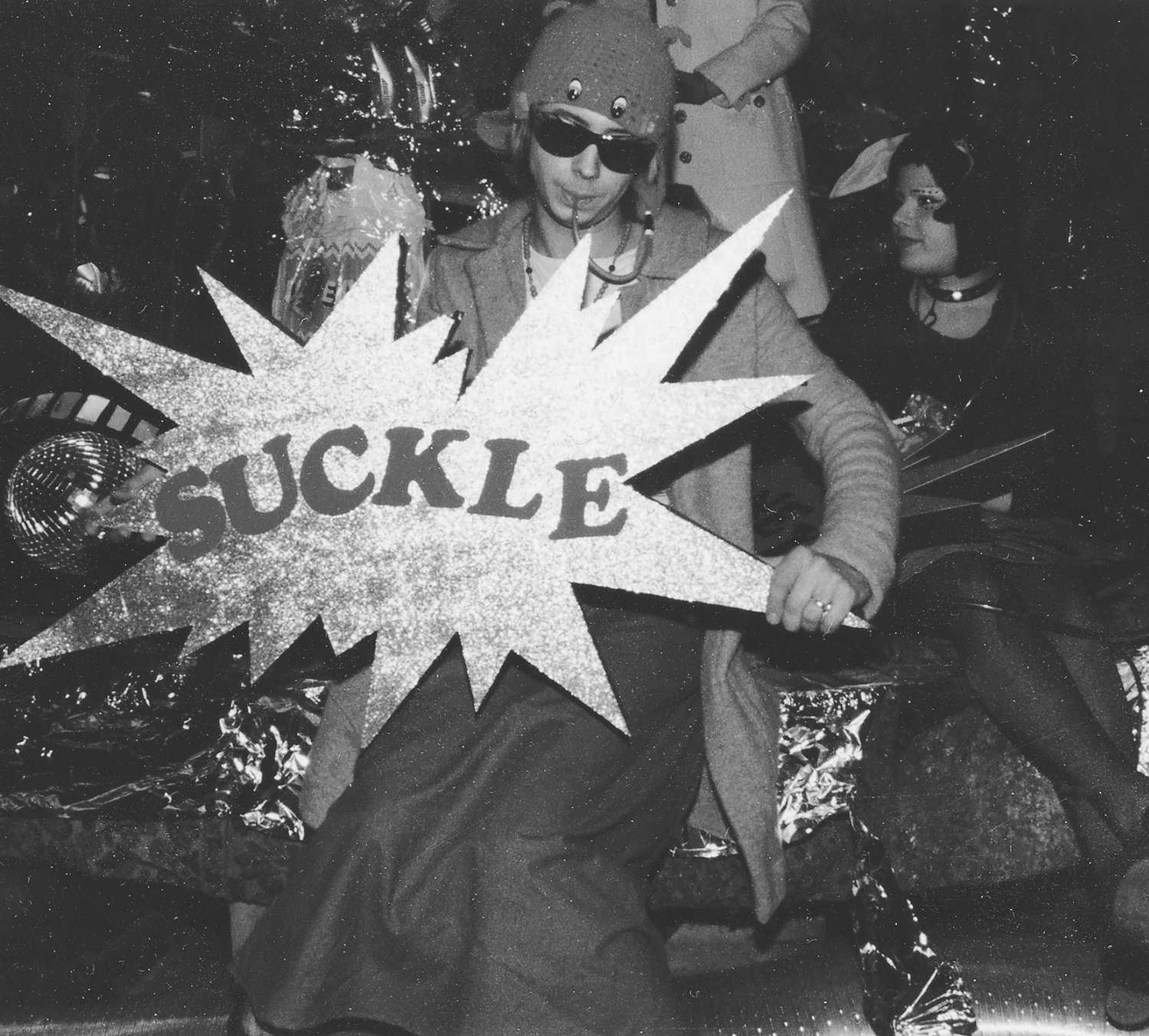

There are some initiatives, but I think more work toward diversity and anti-discrimination could be done. Apart from the projects (Cake&Cash Curatorial Collective, Heike Mutter’s Folgendes, the seminars by Hanne Loreck, Astrid Mania, Michaela Ott, Anja Steidinger, Nora Sternfeld, and Michaela Melián), my seminar series “Non-knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image” as well as Alice Peragine’s “Approximates” seminar both incorporate queer positions and perspectives, and connect these to intersectional standpoints and practices through guest speakers, student works, films, and texts. There is always a risk that diversity just becomes a topic or about representation, and that discriminatory norms and hierarchies can stay intact. To take diversity seriously, it also needs to include practices that lead to structural change. I believe that having a more diverse faculty would be one important step in the right direction.

Dr. Astrid Mania, Professor of Art Criticism and Modern Art History

In my capacity as an art historian, I am by default entangled in a Western mode of thought. But that also implies the question as to how to deal with the so-called canon—that is, the traditional(ly) white, male, Western narrative that is at the core of my discipline. I don’t want to ignore it, but certainly not reinforce it either. So I’m treating it as part of art history’s history. Narratives respond and react to each other, and feminist or post-colonial approaches are no exceptions, so I feel we need a thorough understanding of the ideology and its representational modes that these critical discourses contest. It is important to me to convey that art history is human-made: it reflects very different philosophical, economic, and ideological interests and contexts that we can identify and challenge, if deemed necessary. One way to help me out of my dilemma is to look at art history through a historical lens. As an example, I dedicate an entire lecture to Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon. Now, you could of course ask, why speak about Picasso at all, but why not speak about how Picasso became the “über-artist” that he was and maybe still is for some, what male role model he represents, and why it became so influential, how public institutions and the art market helped establish his career. By looking at the different perspectives under which Picasso’s Demoiselles were discussed over time—from a focus on formal and iconographic aspects to feminist readings—we can see the different approaches to art and in art history over the decades. Moreover, we of course need to speak about the relationship between Western modern art and non-European artifacts and their repercussions in contemporary debates. And, last but not least, yes, this would be a very good place to talk about (contemporary) representations of sex work that defy objectification by a male gaze.

Ingo Offermanns, Professor of Graphic Art

In times of change, it is always a challenge to keep pace with ongoing changes. This means that there will always be room for improvement. Since the HFBK Hamburg sees itself as a space for research and discourse, we have made great efforts in recent years to firmly anchor topics such as equality and internationality in life at the university. The fact that these topics are now rightly becoming more nuanced in light of the discourse about diversity represents a new challenge that we face not only in our hiring policy, but also in our day-to-day interactions with each other. And that ultimately means lifelong learning for all members of the university—students as well as teaching staff. Not least due to the involvement of the students, in recent semesters we as a university community have been able to set up workshops and events that specifically deal with issues of diversity. In my view, it is important to connect these new efforts to the research questions that have been developed in recent years. There is no question that we are only at the beginning of this development. And so I hope that we can be curious enough about one another to enable an open and respectful approach to one another, and ultimately grow in and with the diversity discourse.

Text: Seda Yıdız

Seda Yıldız studies with Prof. Astrid Mania, Prof. Valentina Karga and Prof. Jesko Fezer at the HFBK Hamburg. She is a curator and art writer based in Hamburg. Her socially engaged practice is inspired by thinking across disciplines including art, music, design, literature, cinema, and activism.

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

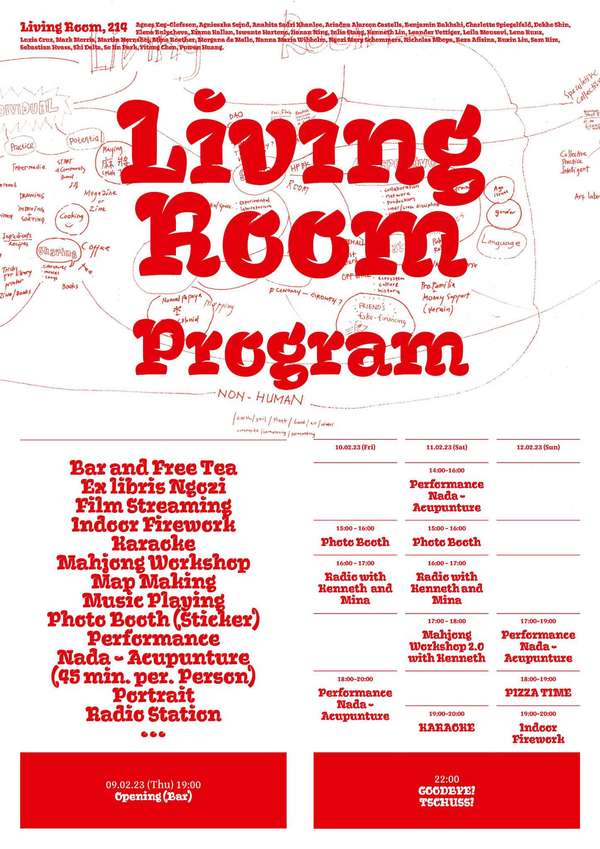

Lange Tage, viel Programm

Lange Tage, viel Programm

Cine*Ami*es

Cine*Ami*es

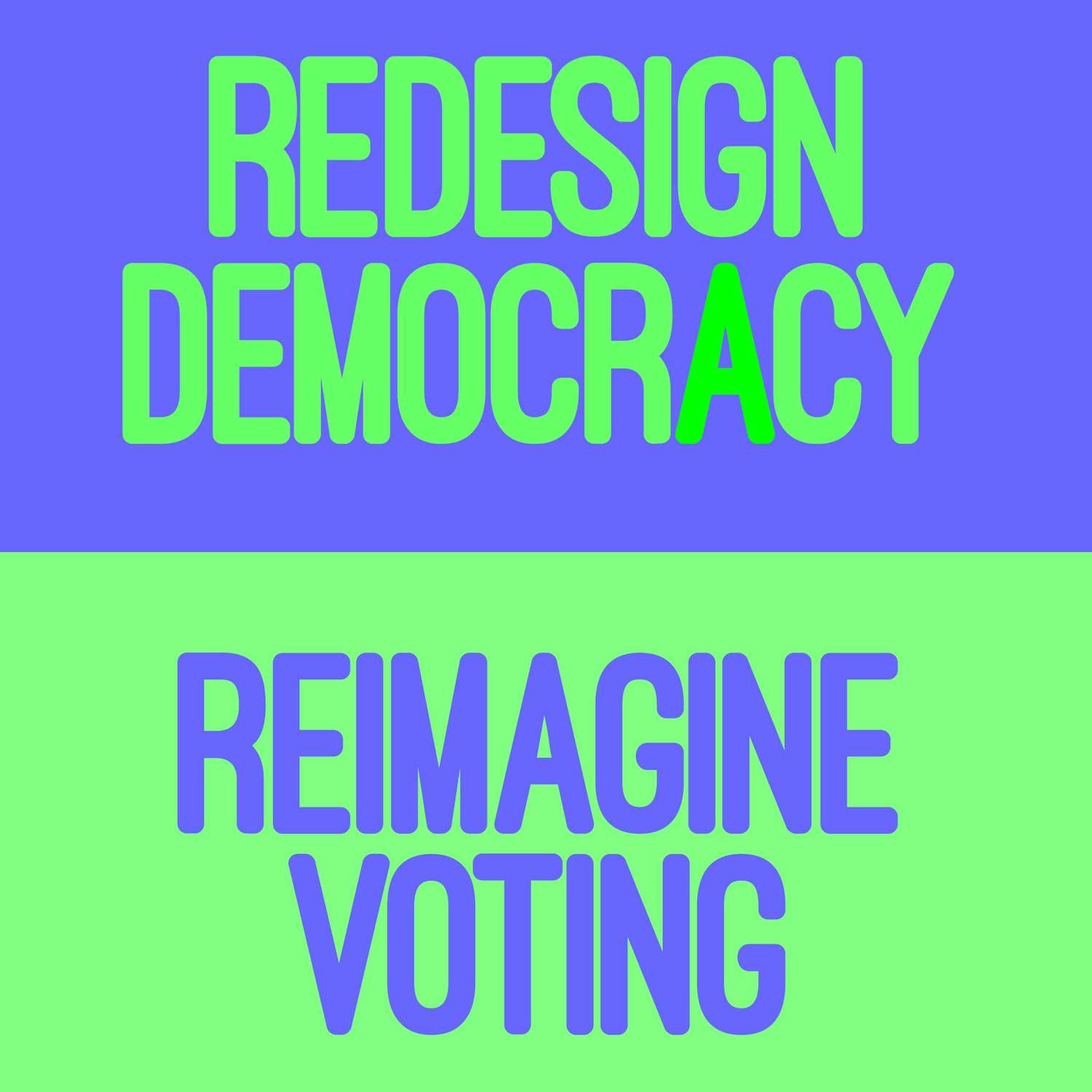

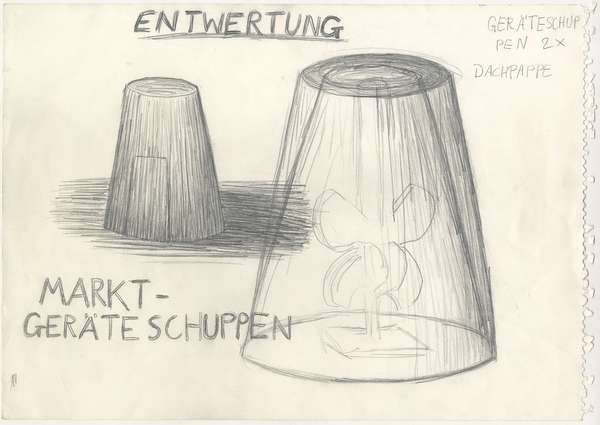

Redesign Democracy – Wettbewerb zur Wahlurne der demokratischen Zukunft

Redesign Democracy – Wettbewerb zur Wahlurne der demokratischen Zukunft

Kunst im öffentlichen Raum

Kunst im öffentlichen Raum

How to apply: Studium an der HFBK Hamburg

How to apply: Studium an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2025 an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2025 an der HFBK Hamburg

Der Elefant im Raum – Skulptur heute

Der Elefant im Raum – Skulptur heute

Hiscox Kunstpreis 2024

Hiscox Kunstpreis 2024

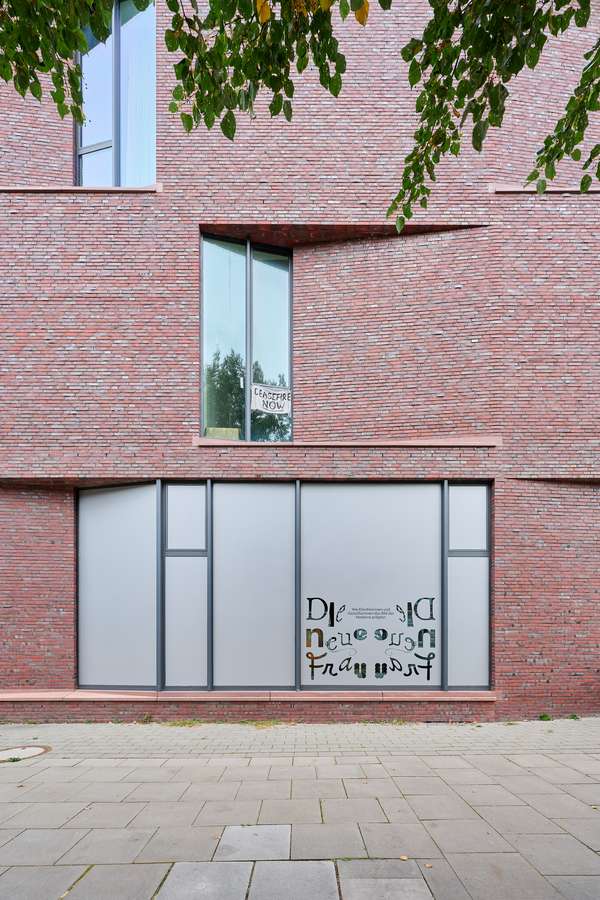

Die Neue Frau

Die Neue Frau

Promovieren an der HFBK Hamburg

Promovieren an der HFBK Hamburg

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Finkenwerder Kunstpreis 2024

Finkenwerder Kunstpreis 2024

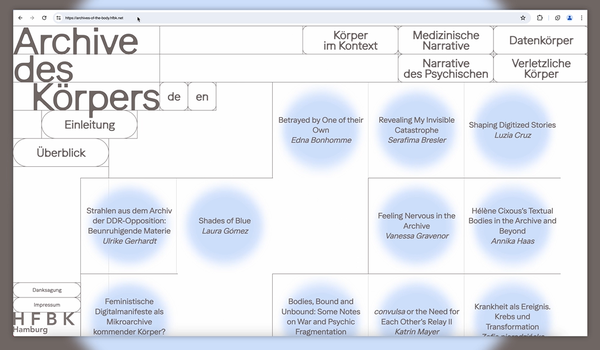

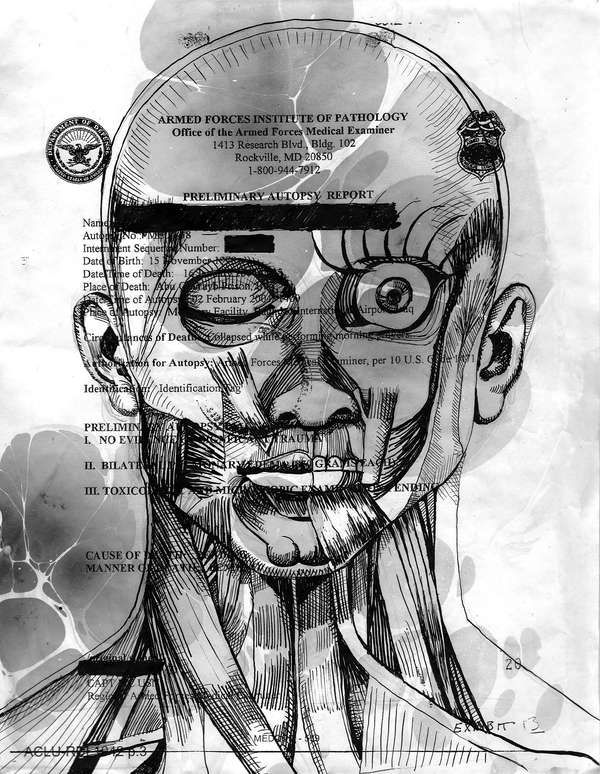

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

Neue Partnerschaft mit der School of Arts der University of Haifa

Neue Partnerschaft mit der School of Arts der University of Haifa

Jahresausstellung 2024 an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2024 an der HFBK Hamburg

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

Extended Libraries

Extended Libraries

And Still I Rise

And Still I Rise

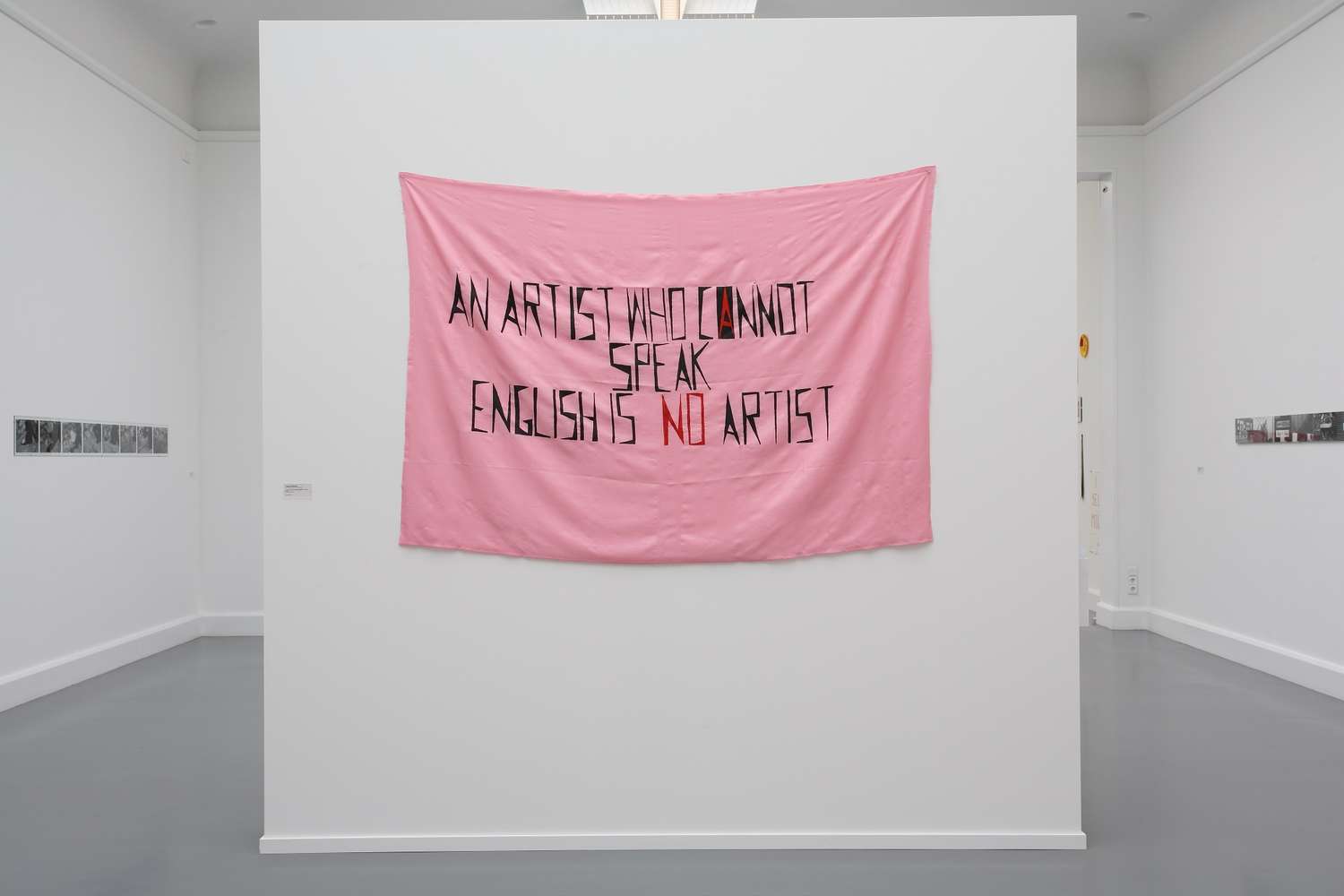

Let's talk about language

Let's talk about language

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

Let`s work together

Let`s work together

Jahresausstellung 2023 an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2023 an der HFBK Hamburg

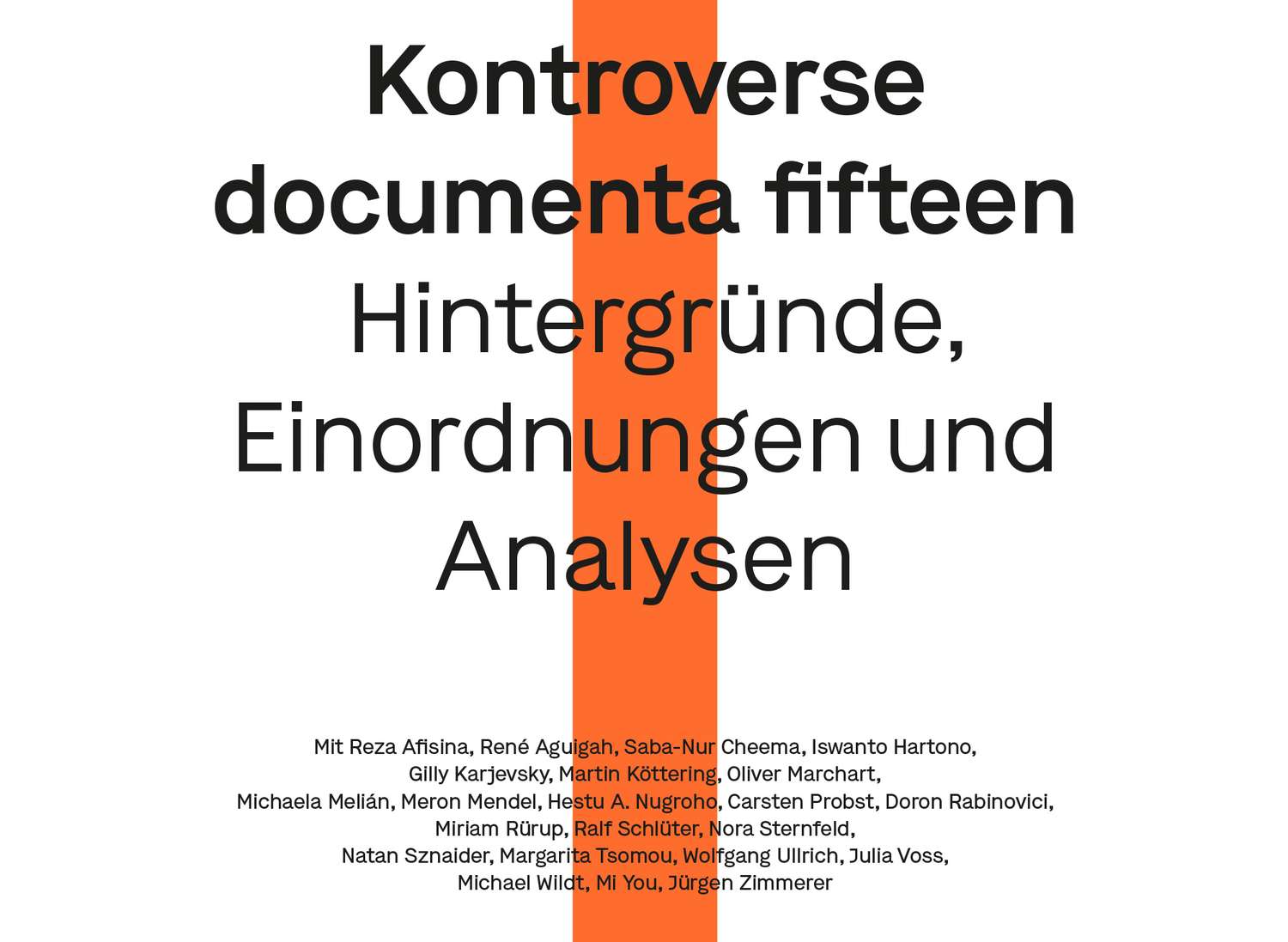

Symposium: Kontroverse documenta fifteen

Symposium: Kontroverse documenta fifteen

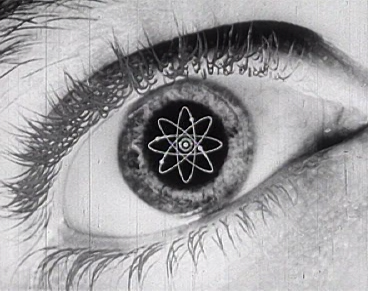

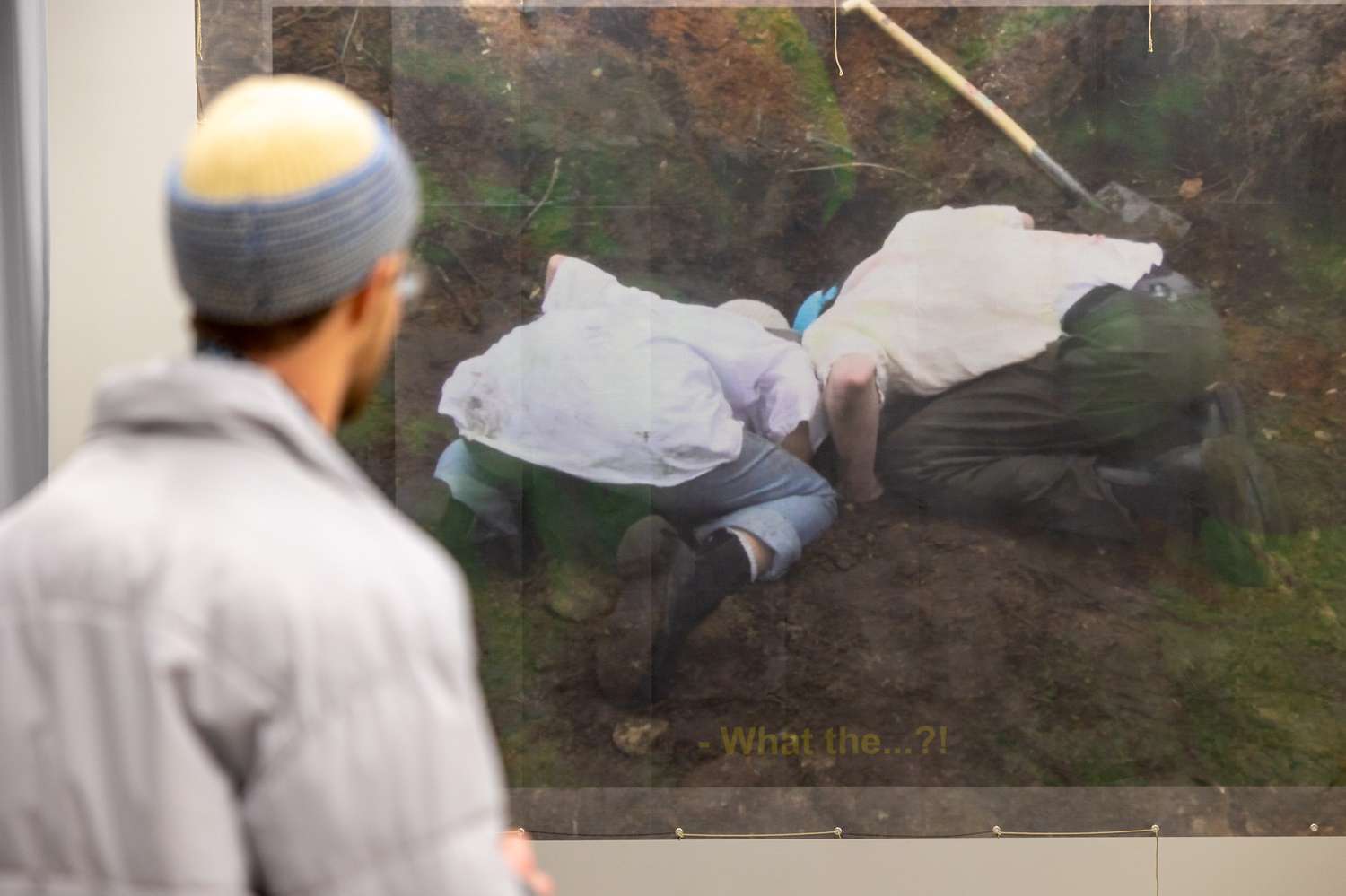

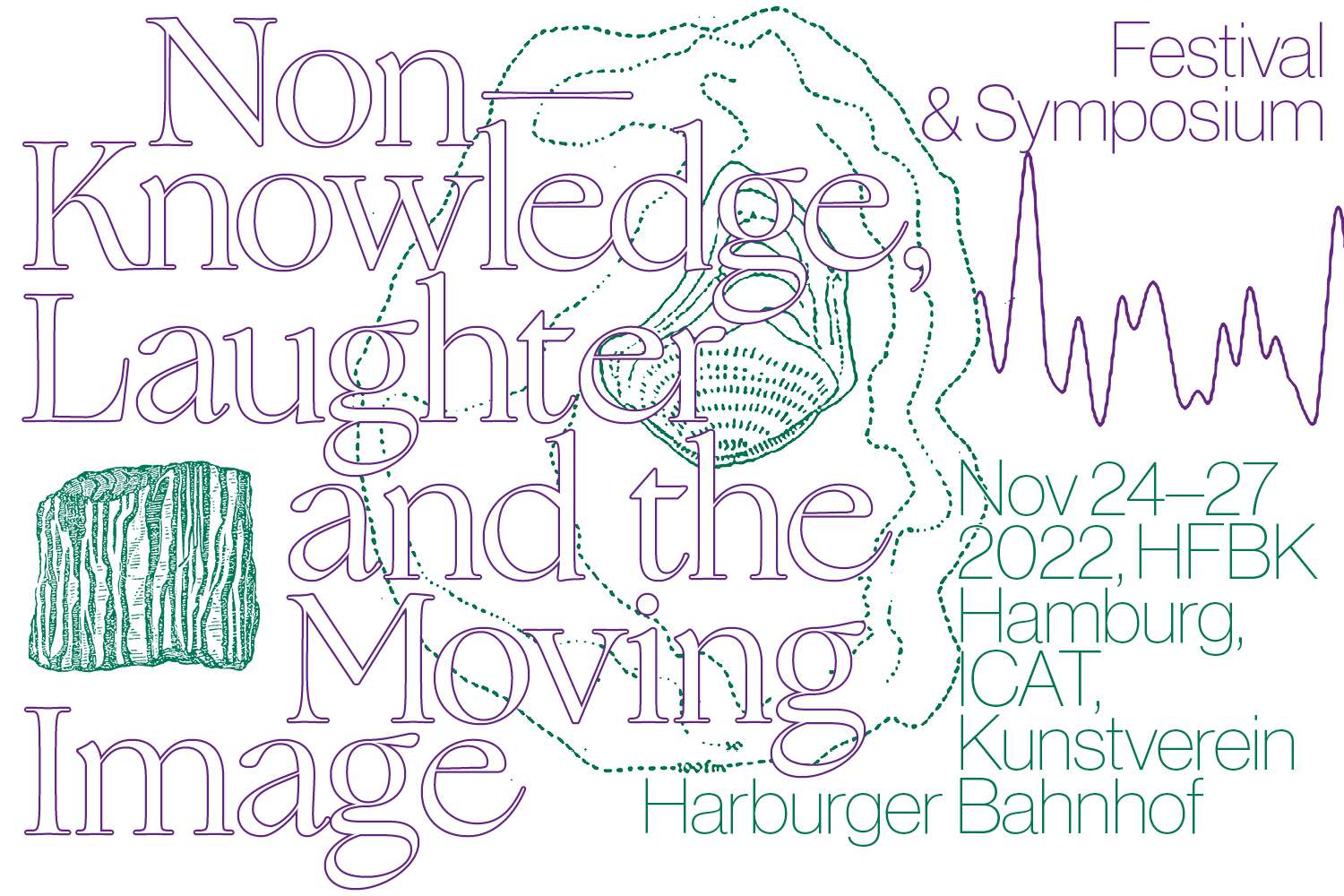

Festival und Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

Festival und Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

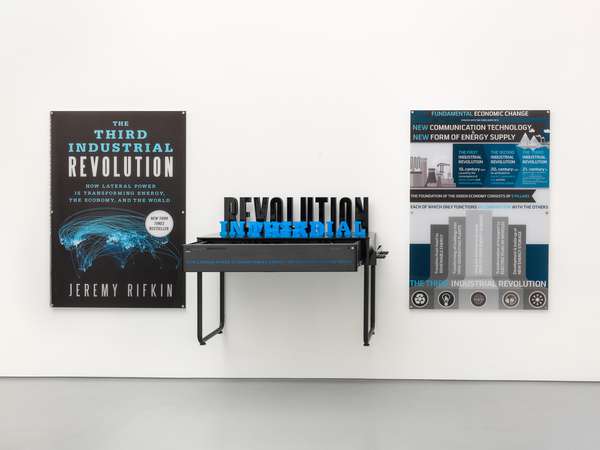

Einzelausstellung von Konstantin Grcic

Einzelausstellung von Konstantin Grcic

Kunst und Krieg

Kunst und Krieg

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

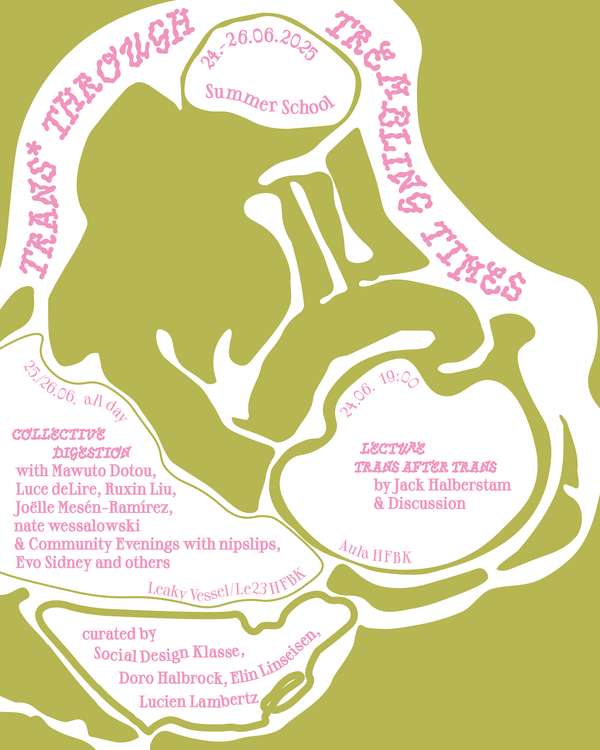

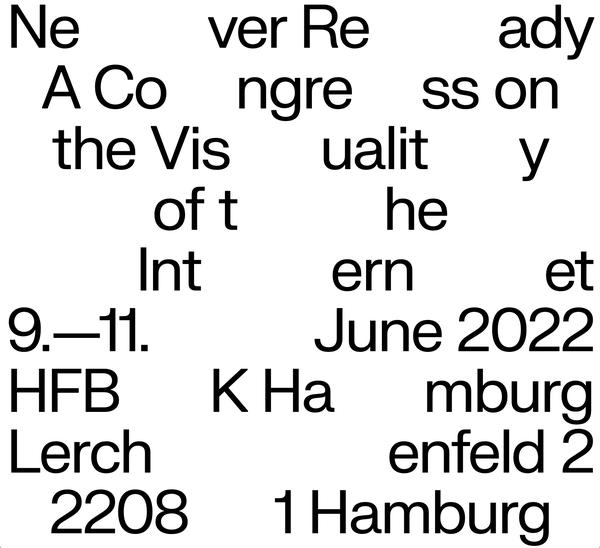

Der Juni lockt mit Kunst und Theorie

Der Juni lockt mit Kunst und Theorie

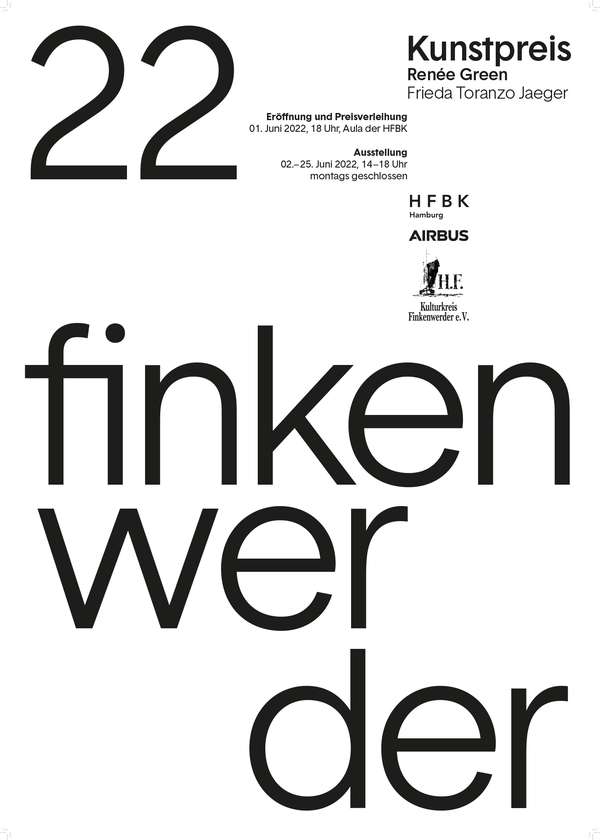

Finkenwerder Kunstpreis 2022

Finkenwerder Kunstpreis 2022

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Raum für die Kunst

Raum für die Kunst

Jahresausstellung 2022 an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2022 an der HFBK Hamburg

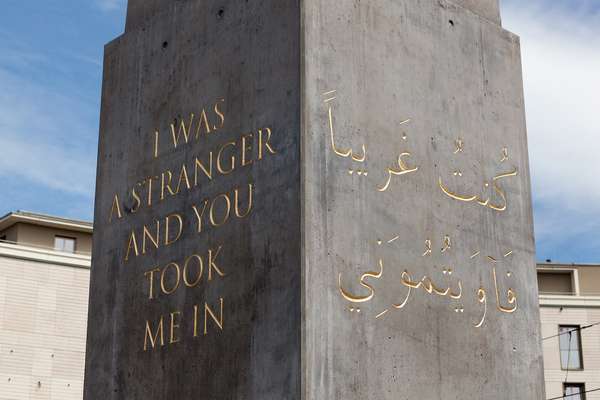

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments

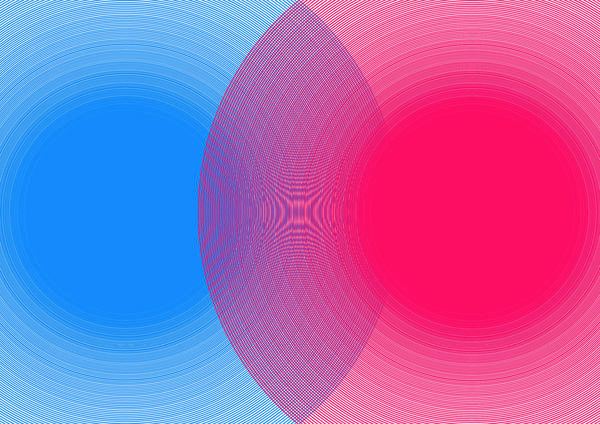

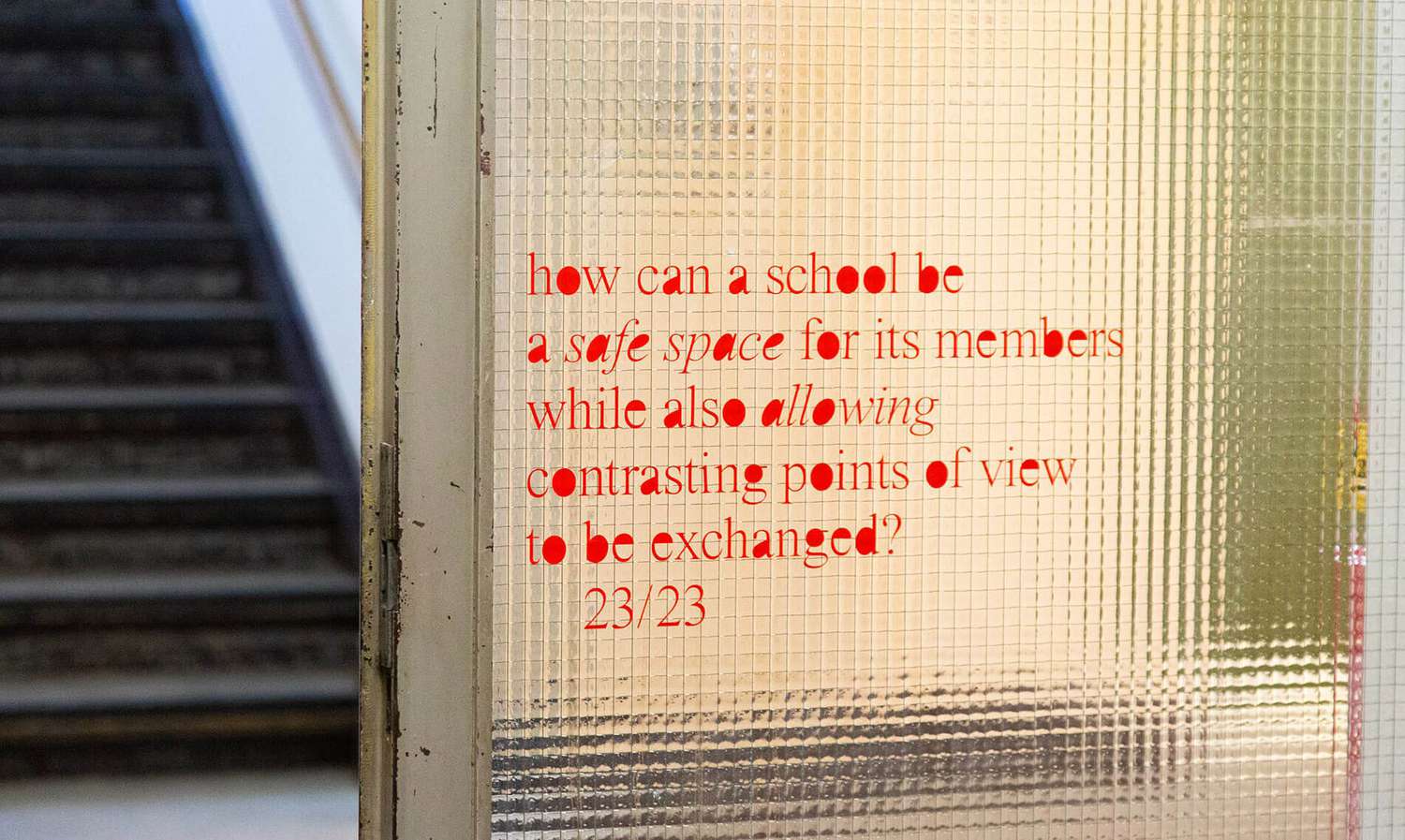

Diversity

Diversity

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

Vermitteln und Verlernen: Wartenau Versammlungen

Vermitteln und Verlernen: Wartenau Versammlungen

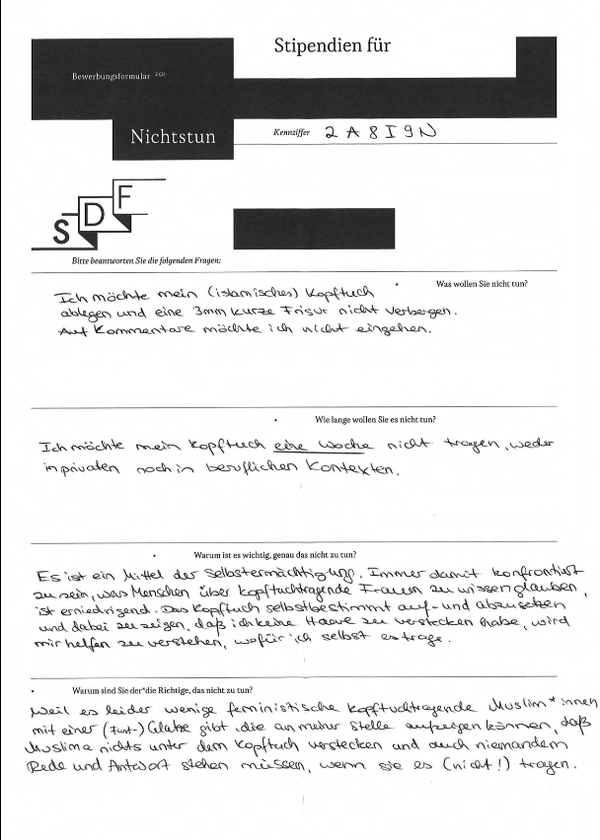

Schule der Folgenlosigkeit

Schule der Folgenlosigkeit

Jahresausstellung 2021 der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2021 der HFBK Hamburg

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

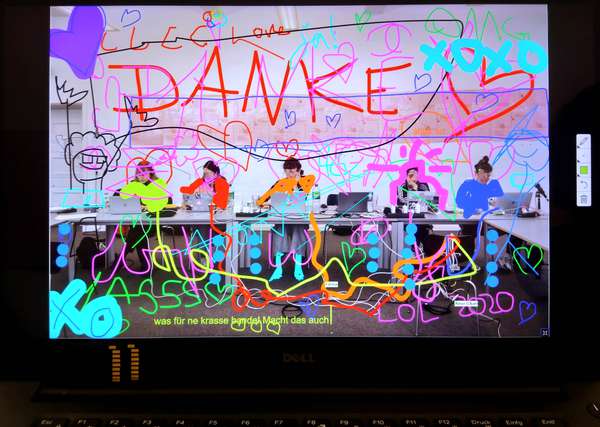

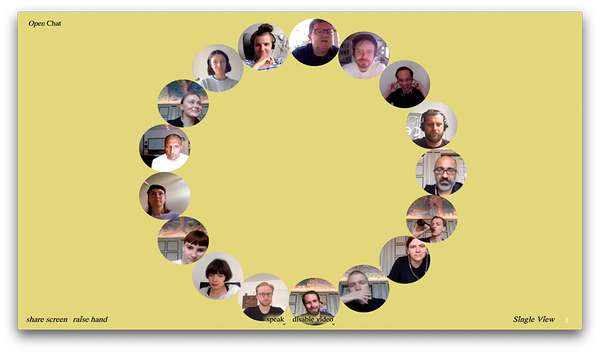

Digitale Lehre an der HFBK

Digitale Lehre an der HFBK

Absolvent*innenstudie der HFBK

Absolvent*innenstudie der HFBK

Wie politisch ist Social Design?

Wie politisch ist Social Design?