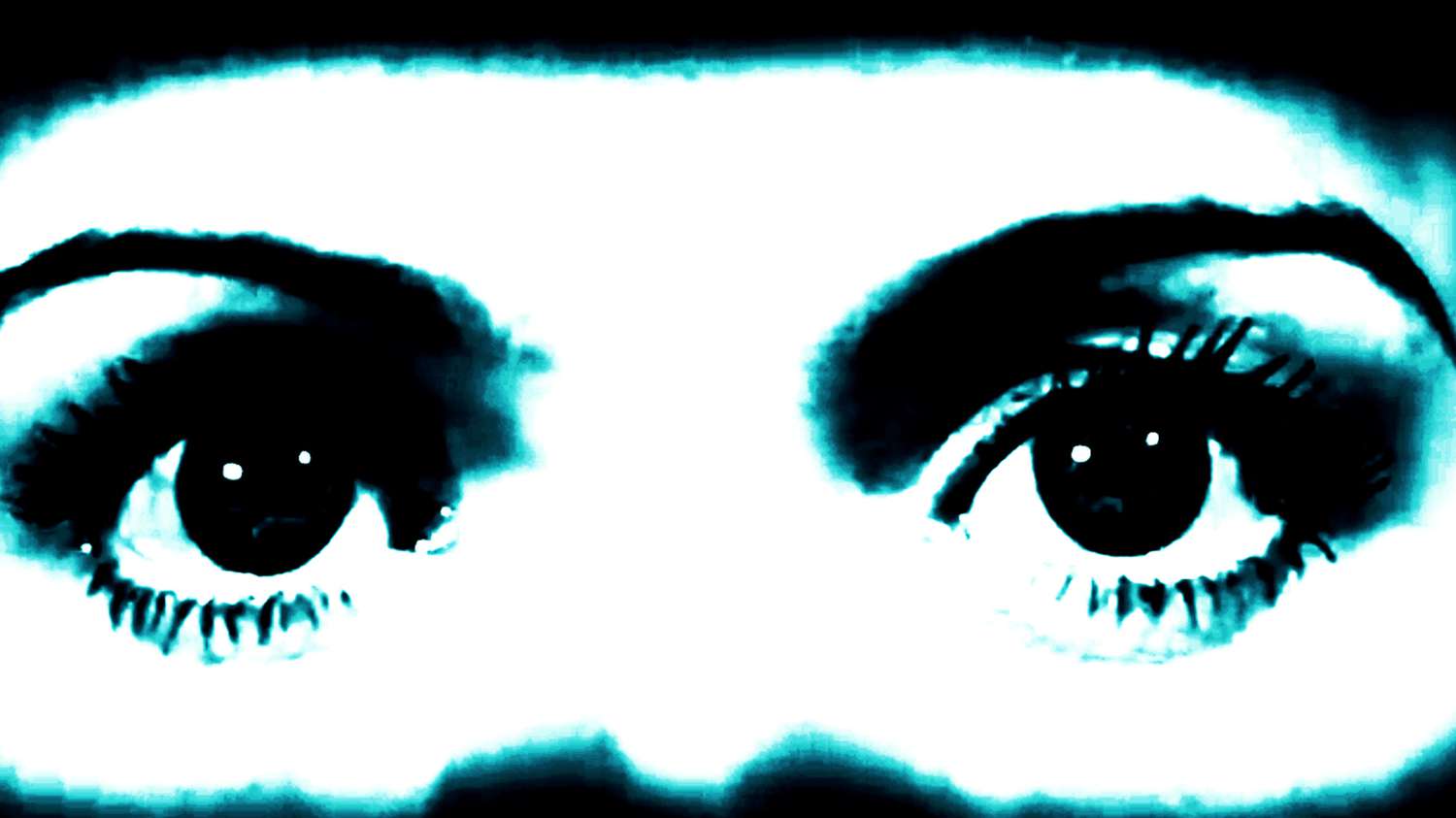

“I am treated as if they have been waiting years for my arrival”

John J. Curley about the first Black woman artist to come to the HFBK Hamburg from the USA in 1958: Mildred Thompson. In addition to her own artistic works reflecting her time in Hamburg, she also participated in the annual Li-La-Le artists' festival with an installation.

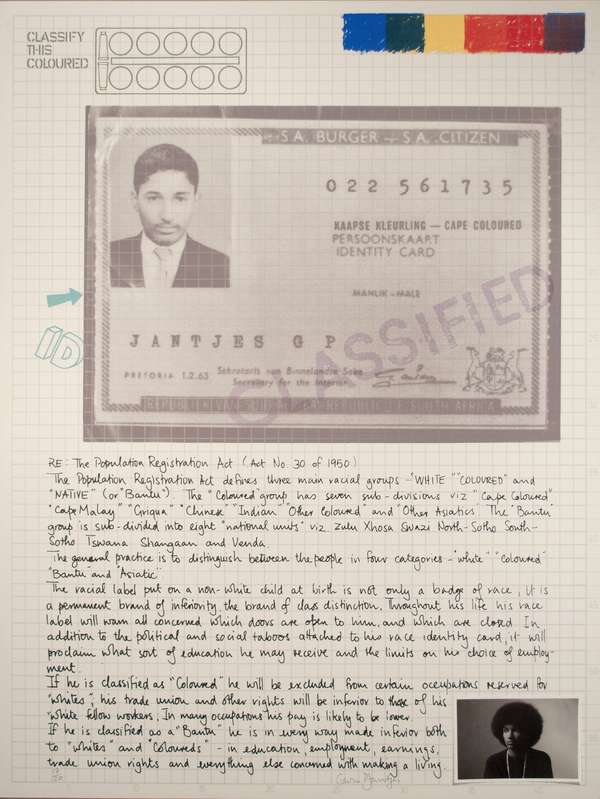

In September 1958, an American expatriate and an exported exhibition arrived in Germany. First, the Black American artist Mildred Thompson arrived for study at HFBK Hamburg. Second, the major exhibition The New American Painting, which featured paintings by Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning, and others, opened in Berlin (at College of Fine Arts, Berlin) on September 1, 1958. This show, organized by the Museum of Modern Art in New York, suggested the originality, commitment, vitality, and heroism of Abstract Expressionism – without including any artists of color and only one woman, Grace Hartigan.[1] Thompson’s voyage to Hamburg is the dialectical other to The New American Painting. Not only did she flee an American art world that would not validate her individualism or talent, but in Hamburg she also embraced a mode of art making that refuted Abstract Expressionism. As opposed to the perceived existential authenticity of Pollock’s and Rothko’s commitment to painting, Thompson embraced a myriad of different styles and techniques during her initial studies in Hamburg – maintaining, simultaneously, an abstract painting and a figurative print practice. As she later recalled about her time in Hamburg, “we were encouraged to master many techniques in many media.”[2]

Hamburg was home to many exiles in the years after World War II. While some 200,000 central and Eastern European refugees came to the city, there was not a large Black presence there. As far as I could tell from the HFBK Hamburg archives, there were no other Black students at the academy in 1958. (A Black student from South Africa, Abass Jacobs, did enroll the following year.[3]) As such, Thompson became something of a curiosity in Hamburg, with a local newspaper publishing an illustrated article about her soon after her arrival.[4] Thompson was surprised at all this attention. She discussed this in a letter to her undergraduate mentor at Howard University, the art historian and artist James Porter:

“The German people are wonderful, I have never met people so warm, gracious and sincerely concerned. They go all out of their way to make things comfortable and clear for me. I am treated as if they have been waiting years for my arrival.”[5]

She continued her letter by suggesting that receiving all this attention was due to her being Black, especially a Black woman. As some scholars have noted, jazz gained widespread acceptance in West Germany partly to signal a symbolic break with the murderous violence of the Nazi past.[6] Might Thompson’s own experience be another version of this – West Germans going out of their way to be friendly to one of the only Black American women in Hamburg? At the same time, however, the local paper could not help but exoticize and racialize Thompson by emphasizing her interest in the singing of Black spirituals, “with her fascinating voice.” As Zora Neale Hurston famously noted in 1928, “I feel most colored when I am thrown against a sharp white background.”[7] Thompson’s personal experiences as a Black woman in an overwhelming white city certainly informed the work she made in Hamburg.

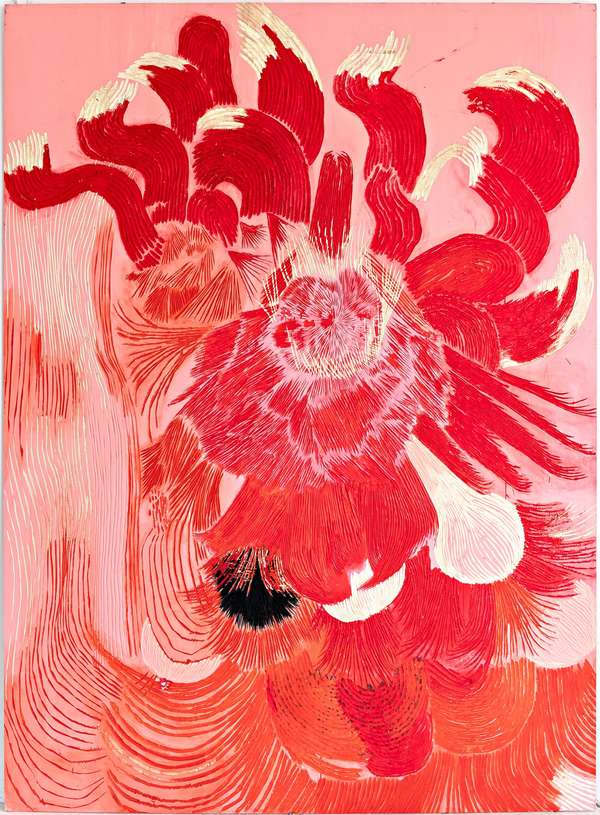

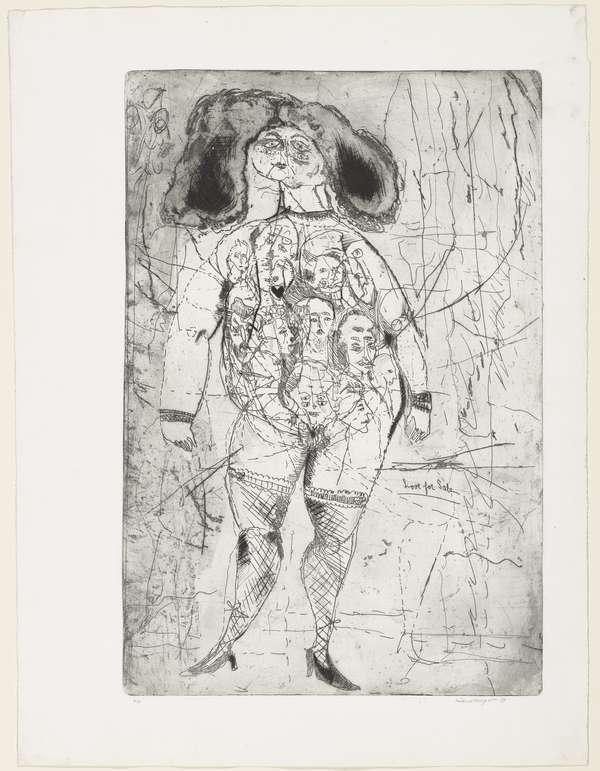

Thompson primarily worked with professors Arno and Emil Schumacher (painting), as well as Paul Wunderlich (printmaking). Hamburg printmaking legend Horst Janssen was also an influence, as he often was around using the academy’s presses. While Thompson’s paintings from this period have disappeared, her surviving prints draw on Germanic traditions and other artistic currents whose stories have been overlooked thanks to the period’s transatlantic focus on large abstract paintings. The form and content of Love for Sale – a Thompson etching from 1959 that ostensibly pictures a sex worker – is impossible to conceive without its Hamburg and German context, for example. The subject matter refers to the legalized sex work in the Reeperbahn neighborhood; its dark, surrealist eroticism is straight out of Wunderlich; and its obsessive and detailed mark-making betrays Janssen’s influence.

The print presents a dark fairy tale – with each paid encounter, the face of the client becomes etched (or tattooed) on the woman’s torso.[8] Is this etching also something of a surrogate self-portrait – referring to the selling of art works as an extension of Thompson’s racialized self in the overwhelmingly white city of Hamburg? And perhaps the work can even reference the slave trade, another instance when bodily autonomy was traded for money.

One could not (and indeed still cannot) live in Hamburg without being aware of vast international shipping networks. Indeed, international shipping has long been the source of the city’s wealth and relative independence; it is the reason for the city’s existence.[9] Hamburg, then, has its own position relative to the slave trade – how could any maritime power in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries not be engaged, at least indirectly, in that horrific practice? While enslaved Africans did not pass through the port, ships returning from the Caribbean and the American South – full of sugar and tobacco – regularly docked in Hamburg.[10]

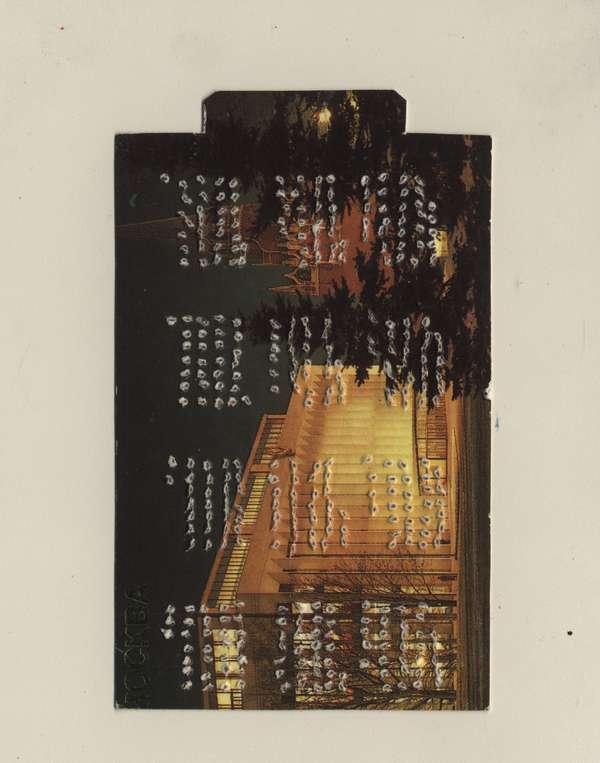

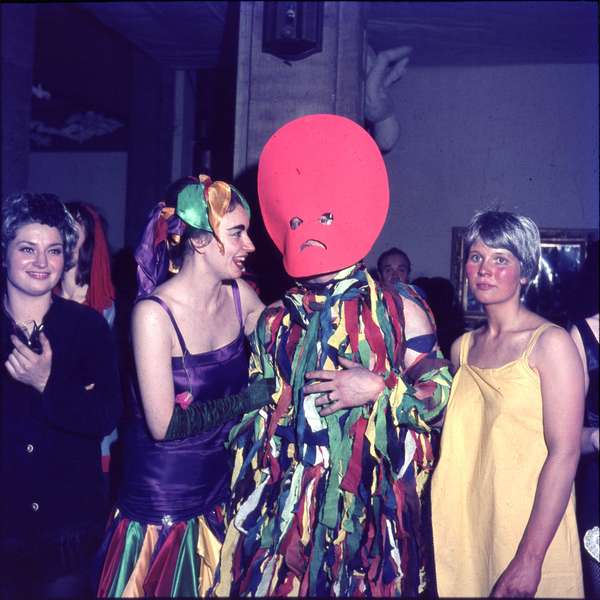

Just a few months after Thompson’s arrival she organized a room for the 1959 iteration of the famous annual carnival at the Hamburg academy, known as Li-La-Le, for which she won a prize. In an unpublished memoir, she describes this environment as presenting a vision of hell, with music provided by “a fine little Dixieland band.” Another source mentions that Thompson included silhouetted figures made from Papier-mâché on the walls.[11] Based on these clues, I was able to locate (with the expert help of Julia Mummenhoff, staff member of the archive of the HFBK Hamburg) photographs that match this description: Black musicians playing in a room surrounded by falling silhouetted figures, perhaps riffing on imagery in Last Judgment scenes from European Renaissance works.[12]

While Thompson’s carnival installation might not be a work of art, it nevertheless can be interpreted through issues of race, like Love for Sale. Violence and entertainment have long been interconnected experiences in Black American life and were especially pronounced in the 1950s. For example, the first major rock and roll hits of Chuck Berry, Little Richard, and Fats Domino in 1955 provided the soundtrack of an America coming to grips with the horrific lynching of Emmitt Till.[13] In early 1959, Thompson constructed a party room that adapts a similar dialectic. While her silhouetted figures look traumatic – screaming while running or being hung upside-down in ways that recall American racial violence – partygoers dance to Black musicians playing jazz.

John J. Curley is Professor of Modern and Contemporary Art History at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, USA. He is the author of A Conspiracy of Images: Andy Warhol, Gerhard Richter, and the Art of the Cold War (Yale University Press, 2013) and Global Art and the Cold War (Laurence King, 2018).

Notes

[1] See The New American Painting (New York: Museum of Modern Art International Program, 1959). The exhibition was on view in Berlin from 01.09.-01.10.1958.

[2] Mildred Thompson, undated biographical statement, Mildred Thompson Papers, Rose Library, Emory University, Box 14, Folder 1.

[3] Thanks to Astrid Mania and Eliane Kölbener for helping me find out more information about Jacobs.

[4] “Ihr Lieblingswunsch: Studium in Hamburg,”, in: Hamburger Abendblatt, November 12, 1958.

[5] Mildred Thompson, letter to Dr. James Porter, September 27, 1958. James Amos Porter Papers, Rose Library, Emory University, Box 44, Folder 38.

[6] Katharina Gerund, “African American Culture in (Postwar) Germany,” in: Transatlantic Cultural Exchange: African American Women's Art and Activism in West Germany, Transcript, 2013, p. 51-100.

[7] Zora Neale Hurston, “How it Feels to be Colored Me” (1928), in: Encyclopedia of African-American Writing, Third Edition, edited by Bryan Conn and Tara Bynum, Grey House, 2015, p. 948.

[8] Julia Mummenhoff has written about this print in terms of tattooing. See her “Das Unsichtbare sichtbar machen,” Lerchenfeld 45, October 2018, p. 3-6.

[9] For centrality of sea trade to the city’s identity, see Matthew Jeffries, Hamburg: A Cultural History, Interlink, 2011, p. 1-38.

[10] Heike Raphael-Hernandez and Pia Wiegmink, “German Entanglements in Transatlantic Slavery: An Introduction,” in: Atlantic Studies, 14:4, 419-435, esp. pp. 423-24.

[11] Thompson describes the room in an unpublished 1975 memoir, Mildred Thompson Papers, Rose Library, Emory University, Box 14, Folder 5. The mention of silhouettes is from Marie Geneviève Ripeau, Mildred Thompson: une artiste pour notre temps, unpublished manuscript, Dossier 1, 69. Mildred Thompson Archives, Atlanta.

[12] Thompson’s silhouettes anticipate the Black American artist Kara Walker’s use of the form in the 1990s to address the grotesque and horrific violence that underpins romanticized imagery of the American South.

[13] These Black American musicians provided the blueprint for the later success of the Rolling Stones and the Beatles. The Beatles arrived in Hamburg in August 1960, playing largely covers of Black American music to rowdy crowds in the Reeperbahn.

This article appeared in Lerchenfeld issue #67.

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

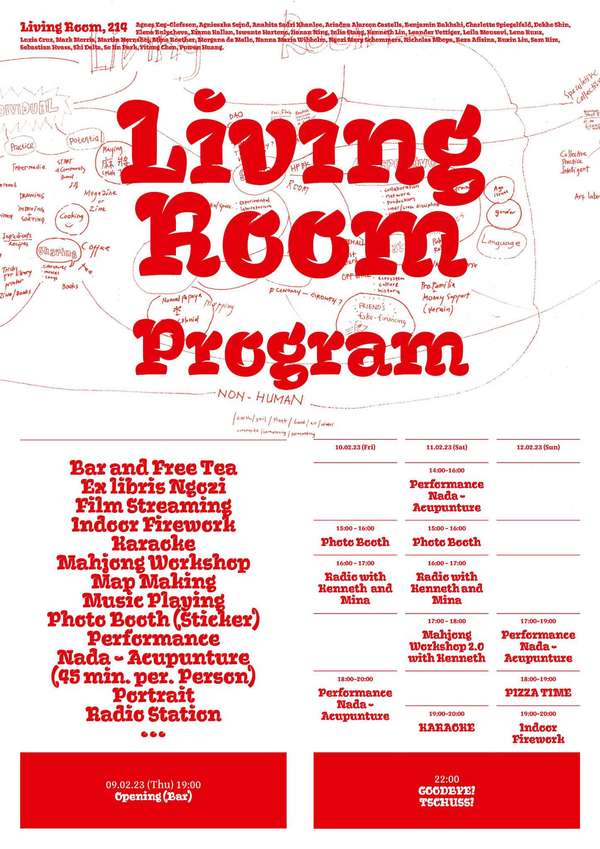

Lange Tage, viel Programm

Lange Tage, viel Programm

Cine*Ami*es

Cine*Ami*es

Redesign Democracy – Wettbewerb zur Wahlurne der demokratischen Zukunft

Redesign Democracy – Wettbewerb zur Wahlurne der demokratischen Zukunft

Kunst im öffentlichen Raum

Kunst im öffentlichen Raum

How to apply: Studium an der HFBK Hamburg

How to apply: Studium an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2025 an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2025 an der HFBK Hamburg

Der Elefant im Raum – Skulptur heute

Der Elefant im Raum – Skulptur heute

Hiscox Kunstpreis 2024

Hiscox Kunstpreis 2024

Die Neue Frau

Die Neue Frau

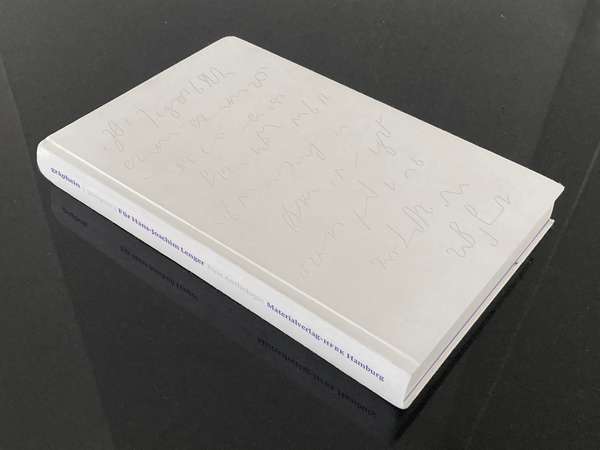

Promovieren an der HFBK Hamburg

Promovieren an der HFBK Hamburg

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Finkenwerder Kunstpreis 2024

Finkenwerder Kunstpreis 2024

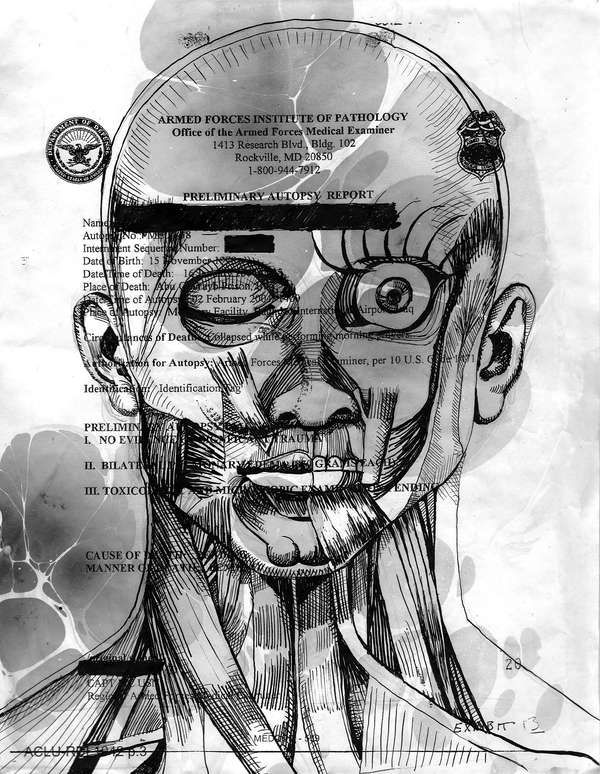

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

Neue Partnerschaft mit der School of Arts der University of Haifa

Neue Partnerschaft mit der School of Arts der University of Haifa

Jahresausstellung 2024 an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2024 an der HFBK Hamburg

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

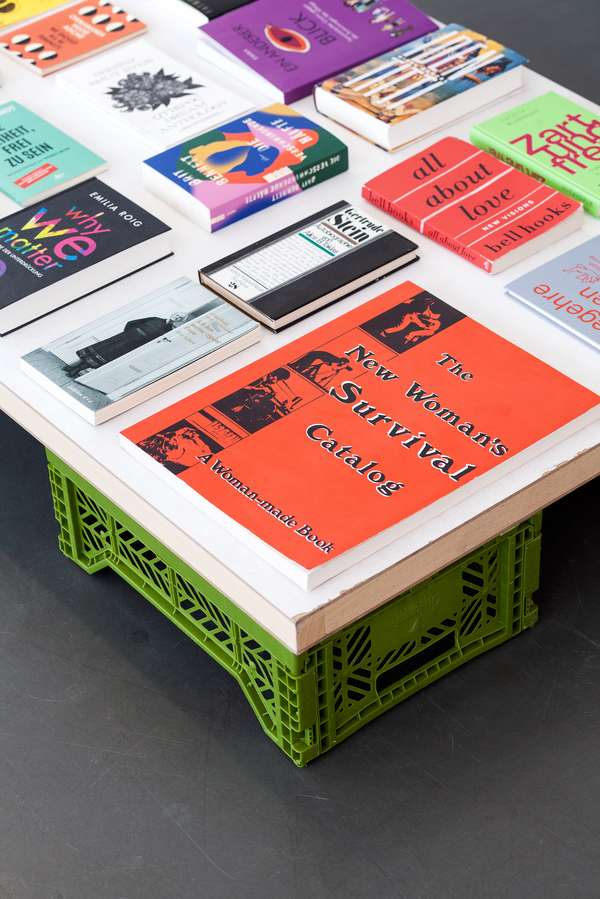

Extended Libraries

Extended Libraries

And Still I Rise

And Still I Rise

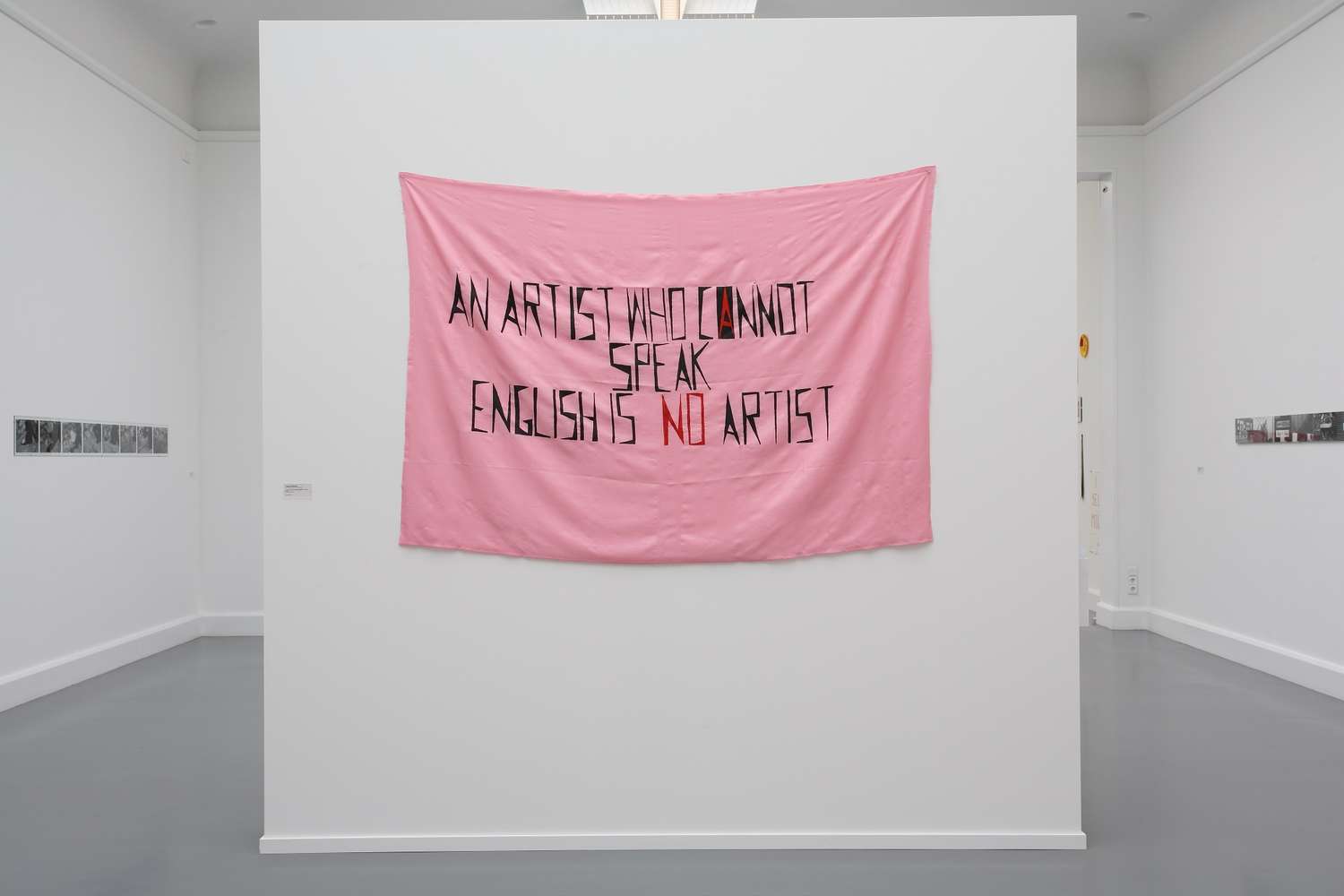

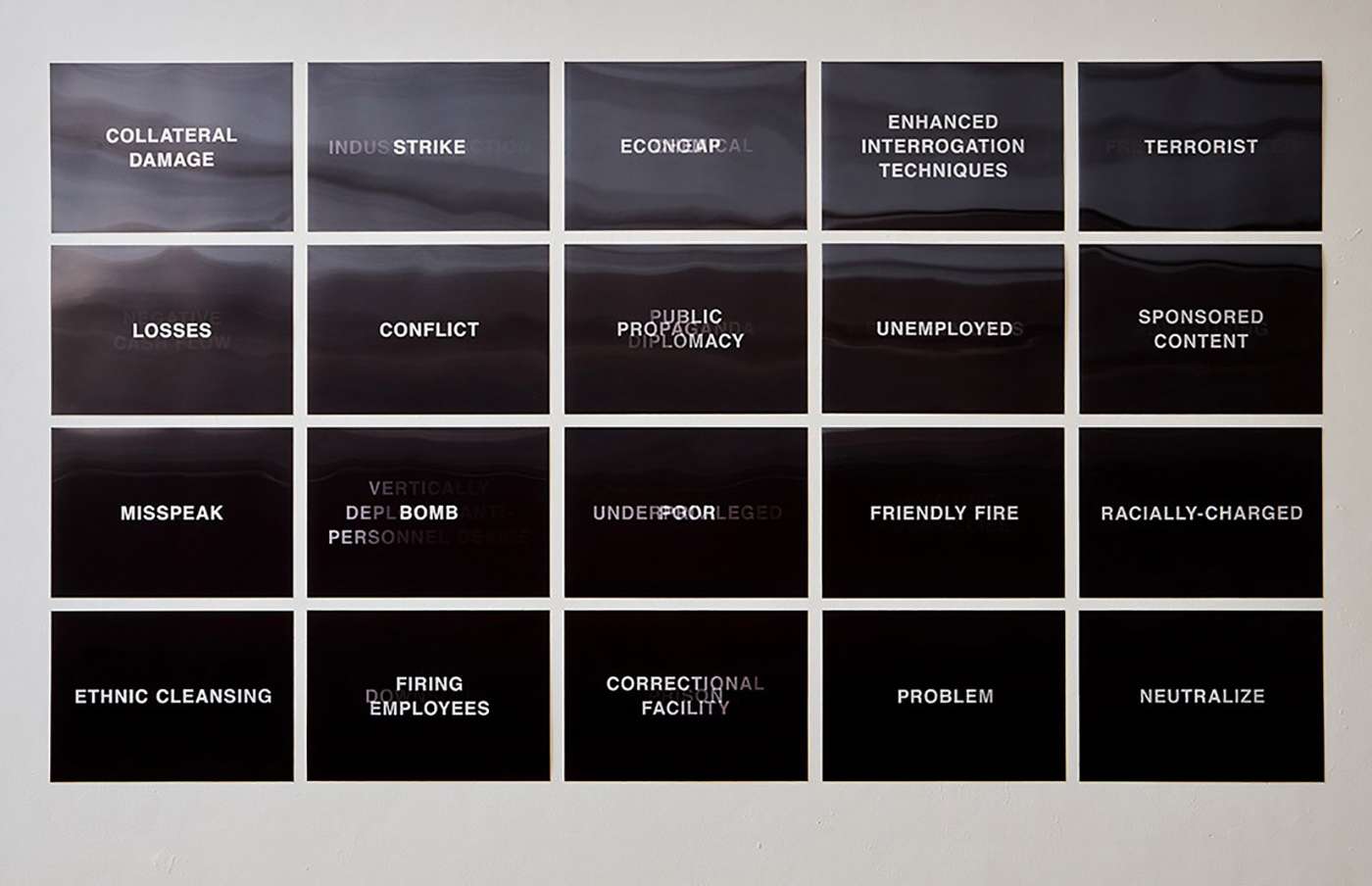

Let's talk about language

Let's talk about language

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

Let`s work together

Let`s work together

Jahresausstellung 2023 an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2023 an der HFBK Hamburg

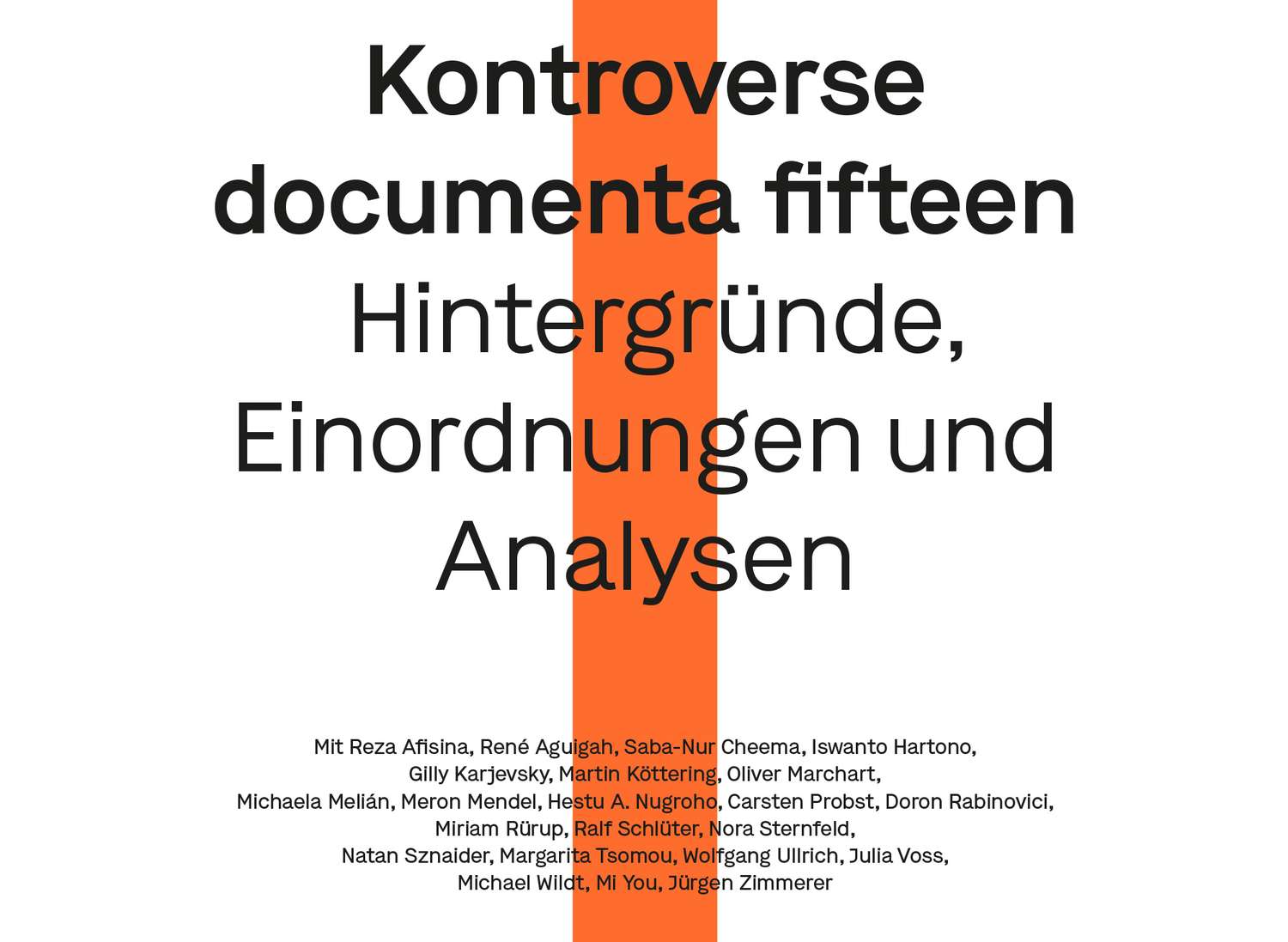

Symposium: Kontroverse documenta fifteen

Symposium: Kontroverse documenta fifteen

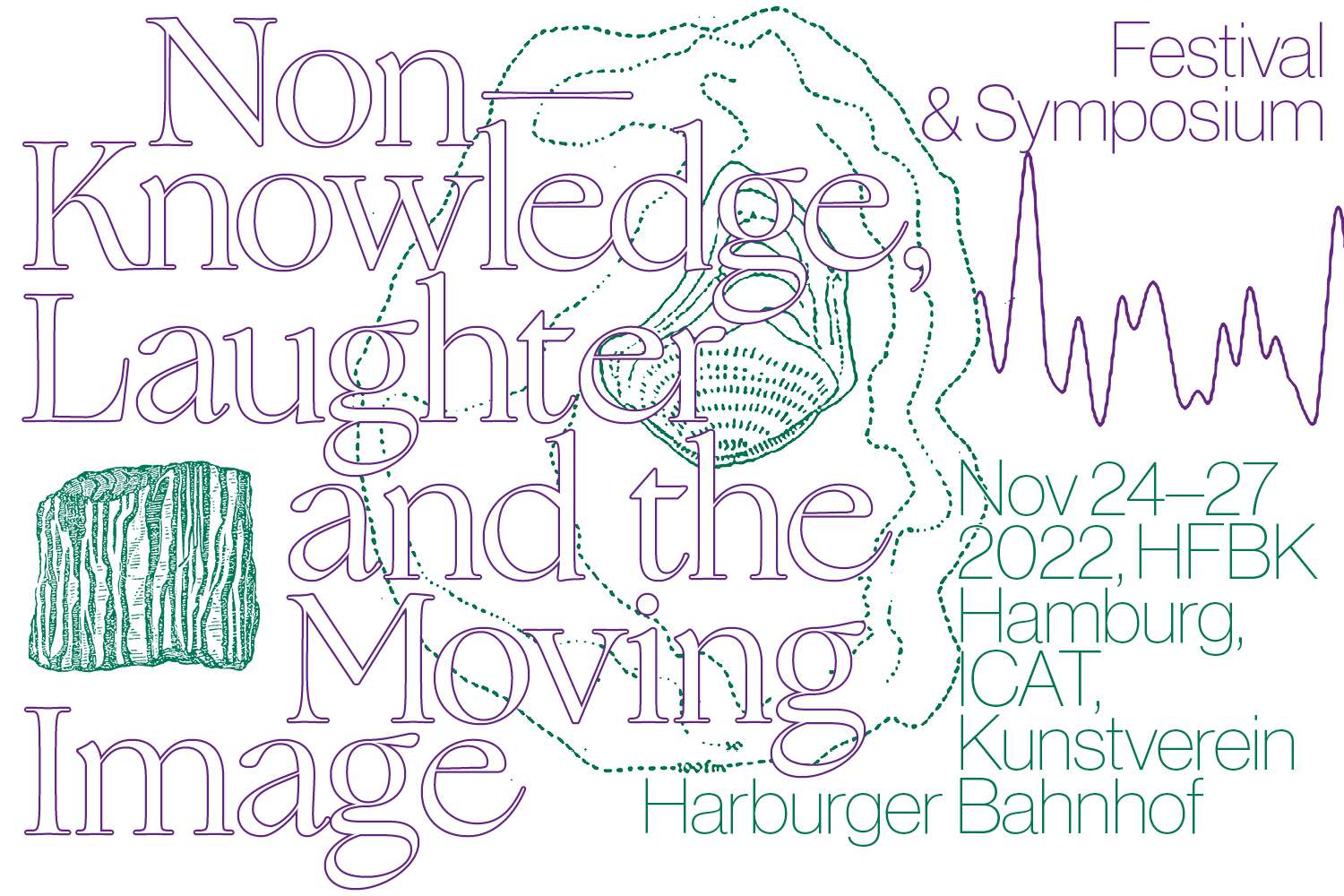

Festival und Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

Festival und Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

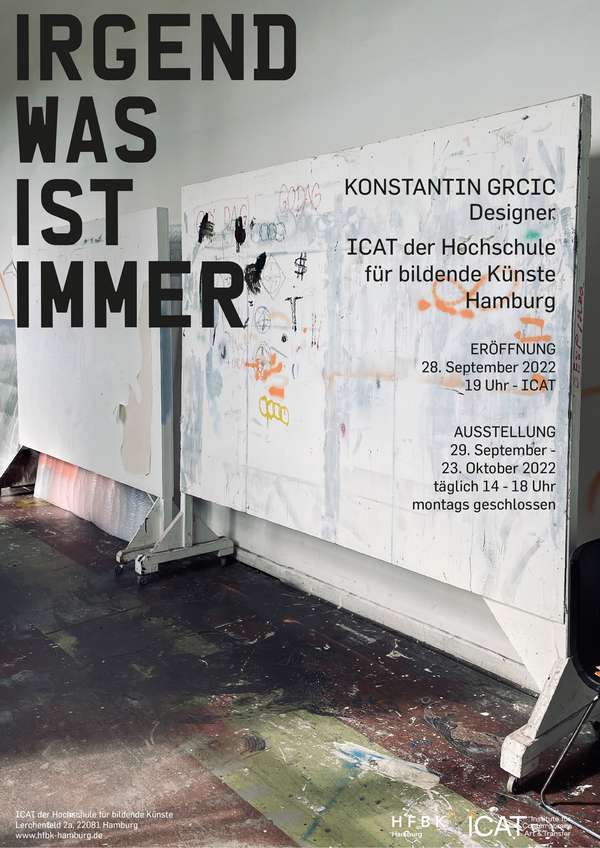

Einzelausstellung von Konstantin Grcic

Einzelausstellung von Konstantin Grcic

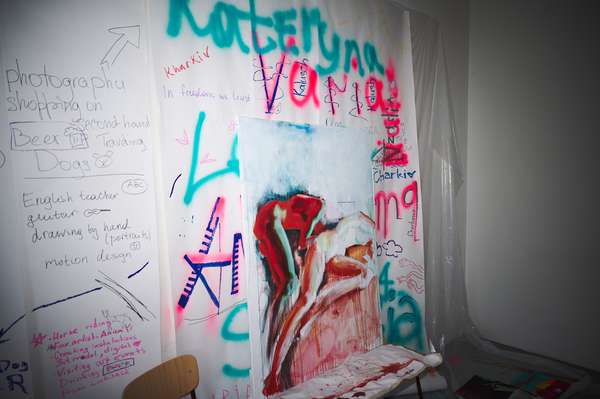

Kunst und Krieg

Kunst und Krieg

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

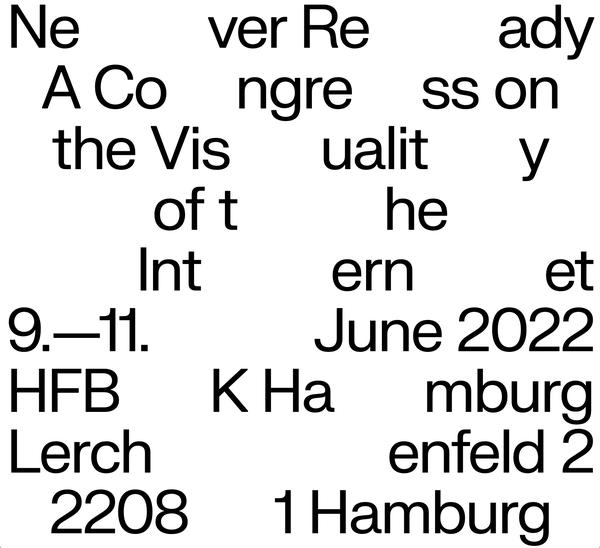

Der Juni lockt mit Kunst und Theorie

Der Juni lockt mit Kunst und Theorie

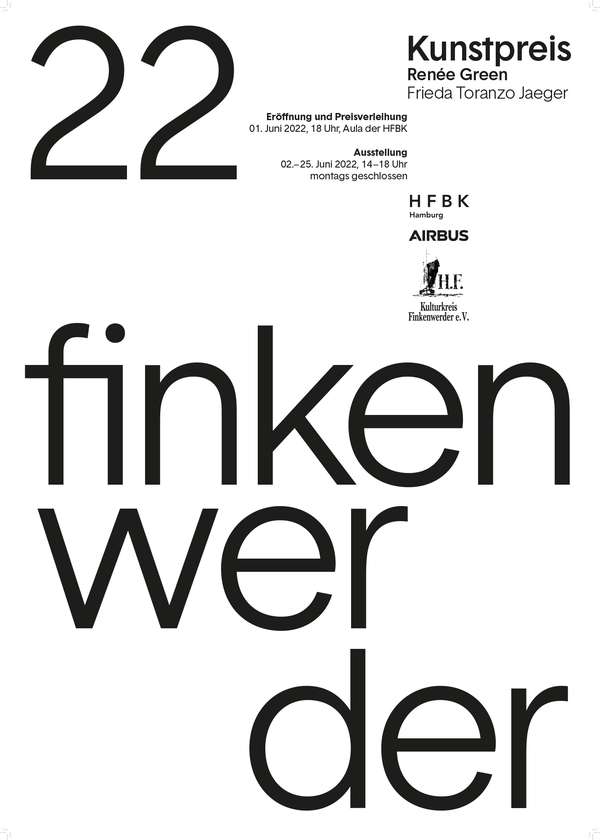

Finkenwerder Kunstpreis 2022

Finkenwerder Kunstpreis 2022

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Raum für die Kunst

Raum für die Kunst

Jahresausstellung 2022 an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2022 an der HFBK Hamburg

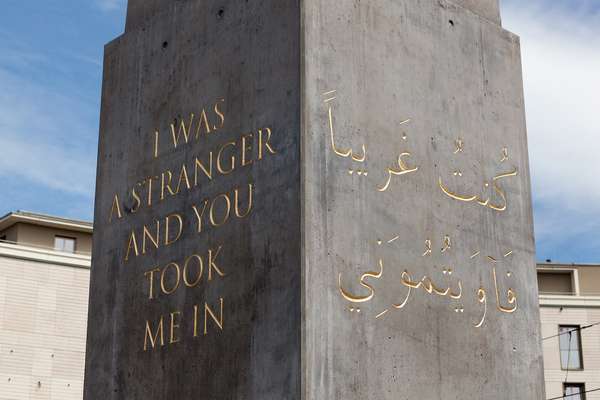

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments

Diversity

Diversity

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

Vermitteln und Verlernen: Wartenau Versammlungen

Vermitteln und Verlernen: Wartenau Versammlungen

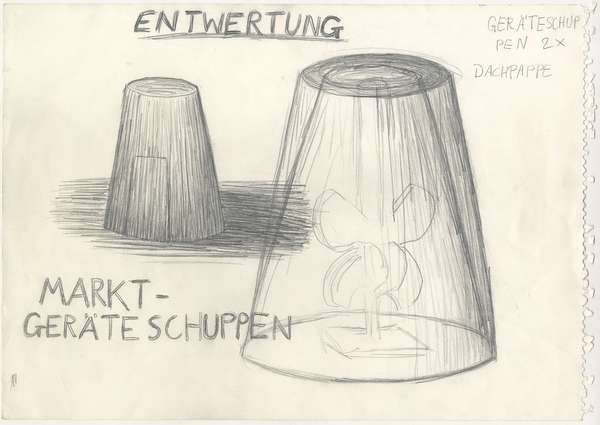

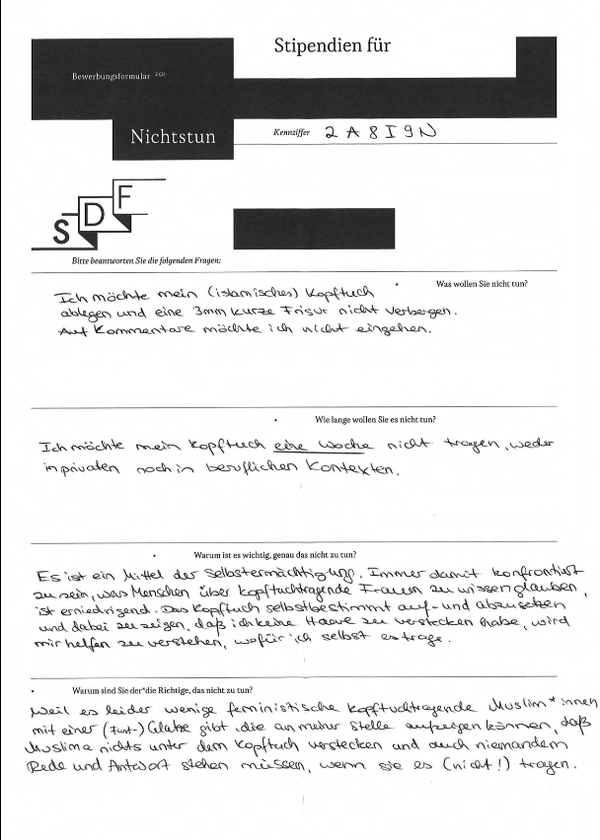

Schule der Folgenlosigkeit

Schule der Folgenlosigkeit

Jahresausstellung 2021 der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2021 der HFBK Hamburg

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

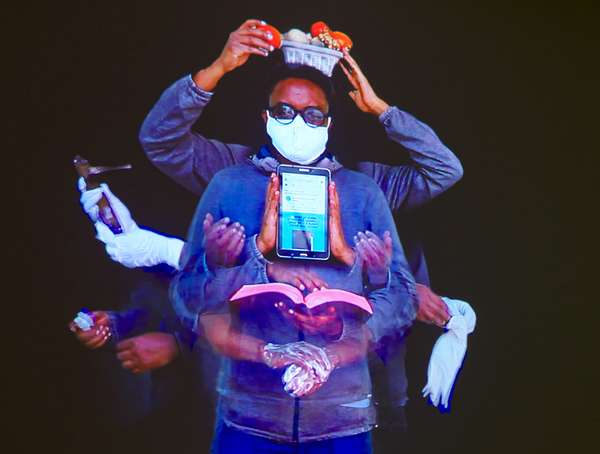

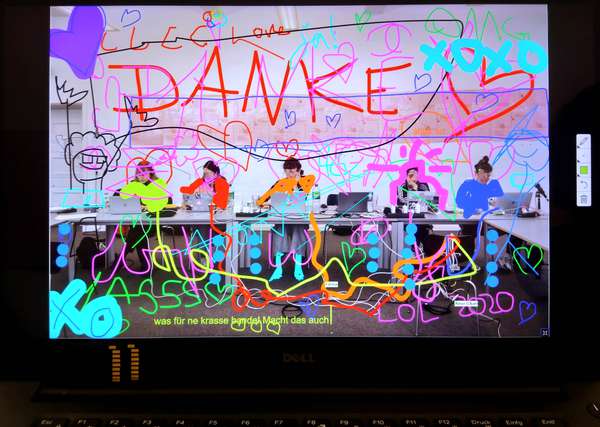

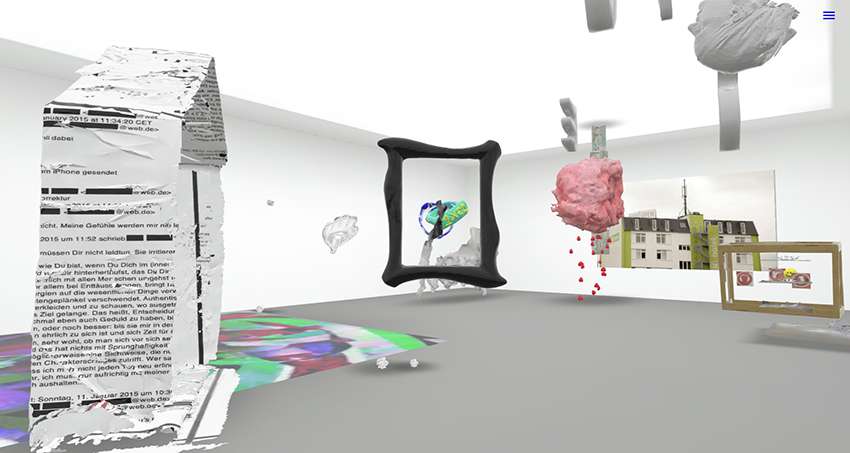

Digitale Lehre an der HFBK

Digitale Lehre an der HFBK

Absolvent*innenstudie der HFBK

Absolvent*innenstudie der HFBK

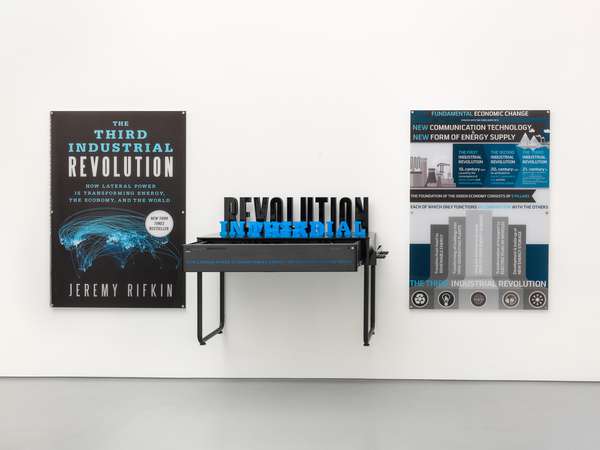

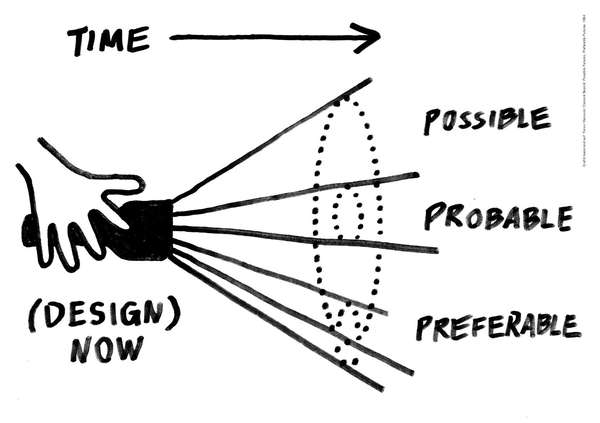

Wie politisch ist Social Design?

Wie politisch ist Social Design?