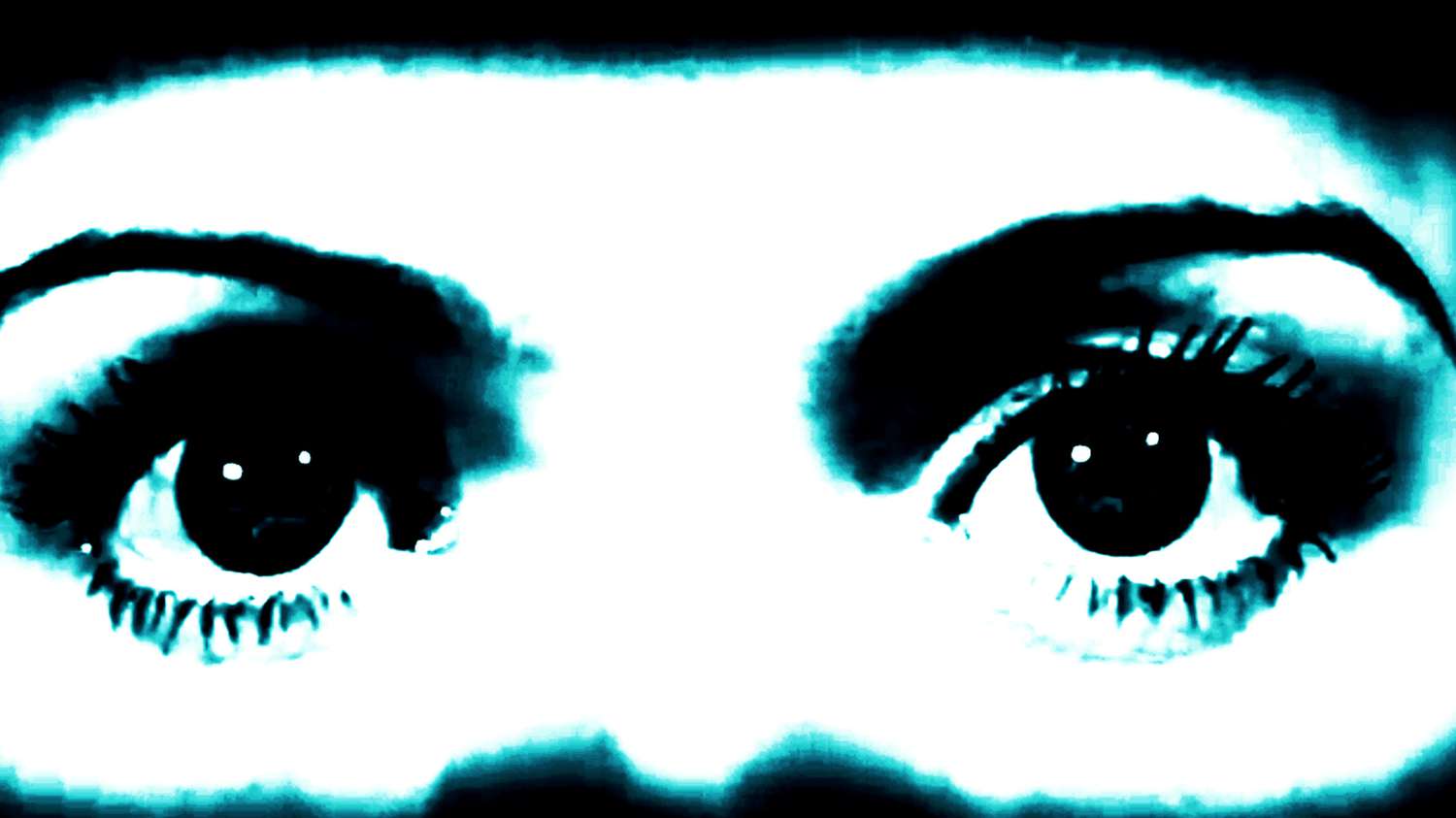

The Images Are Alive: Interview with Prof Annika Larsson

Lerchenfeld: Your research project combines three very unconventional terms, which is laughter, the moving image and non-knowledge. What is meant by each individual term and how do they relate to each other?

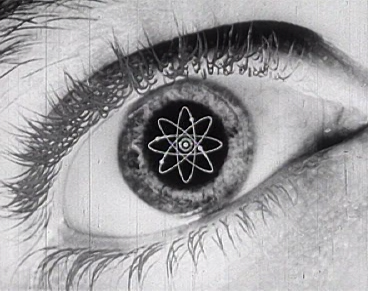

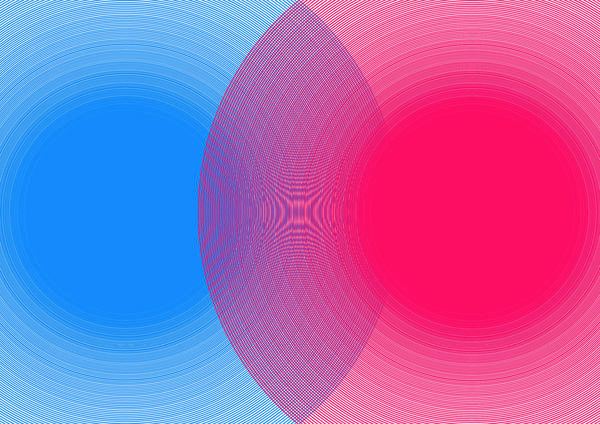

Annika Larsson: The whole project started with the text “Non-knowledge, Laughter and Tears” by Georges Bataille based on a lecture he did in 1953 and where he states that “knowledge demands a certain stability of things known“, whereas “the laughable always remains unknown, a kind of unknown that invades us suddenly, that overturns our habitual course”. Bataille suggests that, “the laughable is not only unknown, but unknowable”, and means that without this sudden invasion of the unknown, one cannot create new thought, nor change anything. Laughter has not only the ability to shatter familiar thoughts, but also the ability to basically turn the world upside down (and shatter official truths). One might say that it builds its own world versus the official world. In that way laughing can have a political potential, be a resistant gesture and queerify the production of knowledge. No dogma, no authoritarianism, no narrow-minded seriousness can coexist with laughter. In many ways the moving image functions in a similar way, in that it has a capacity to build its own world – another time-space that opens up a virtual space in where it becomes possible to visualize another possible thought. Far from being a mere representation of the real world the moving image has an ability to directly act upon us (and our consciousness). It is an active force that changes us as well as the world. So with the moving image you can enter really interesting discussions around what we call real or alive and what we call dead. One common idea is to think of the image as dead material. In my approach of film making or video art I see the image as something highly alive, something that is a player among other players. I am very interested in this feedback relation between images, humans and the world, and how with the mass introduction of cinema at the beginning of the 20th Century our way to perceive the world and ourselves radically changed, and how it keeps on changing with new technology. As Walter Benjamin asserts in his seminal text “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” it is through the camera that we first discover the “optical unconscious”, just as we discover the instinctual unconscious through psychoanalysis. There is a strong connection with these two types of unconscious, which brings the moving image and laughter into a close bound. The effect that laughter produces in us, a feeling of being thrown “out of joint” and “beside ourselves” also happens when the viewer is confronted with the close-up or an unexpected meeting of two conflicting shots in a moving image. Filmmaker and film theorist Sergei Eisenstein has described this psychological effect that forces the viewer to go out of a normal state, into a pre-logic, irrational state, of “pure” affect, feeling and sensation, as something that forces the viewer to jump out of his seat, into a point of ecstasy, which literally means out of state. So, one of the questions this project is asking is whether these moments of becoming “beside ourselves” perhaps could lead to more social, dependent, and relational modes of existence.

Lf.: So does non-knowledge only have positive aspects?

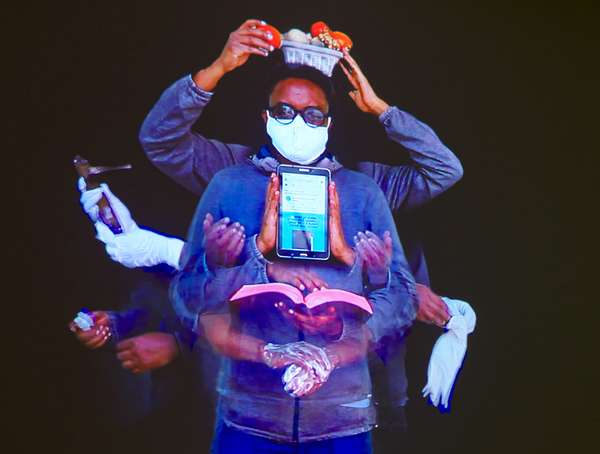

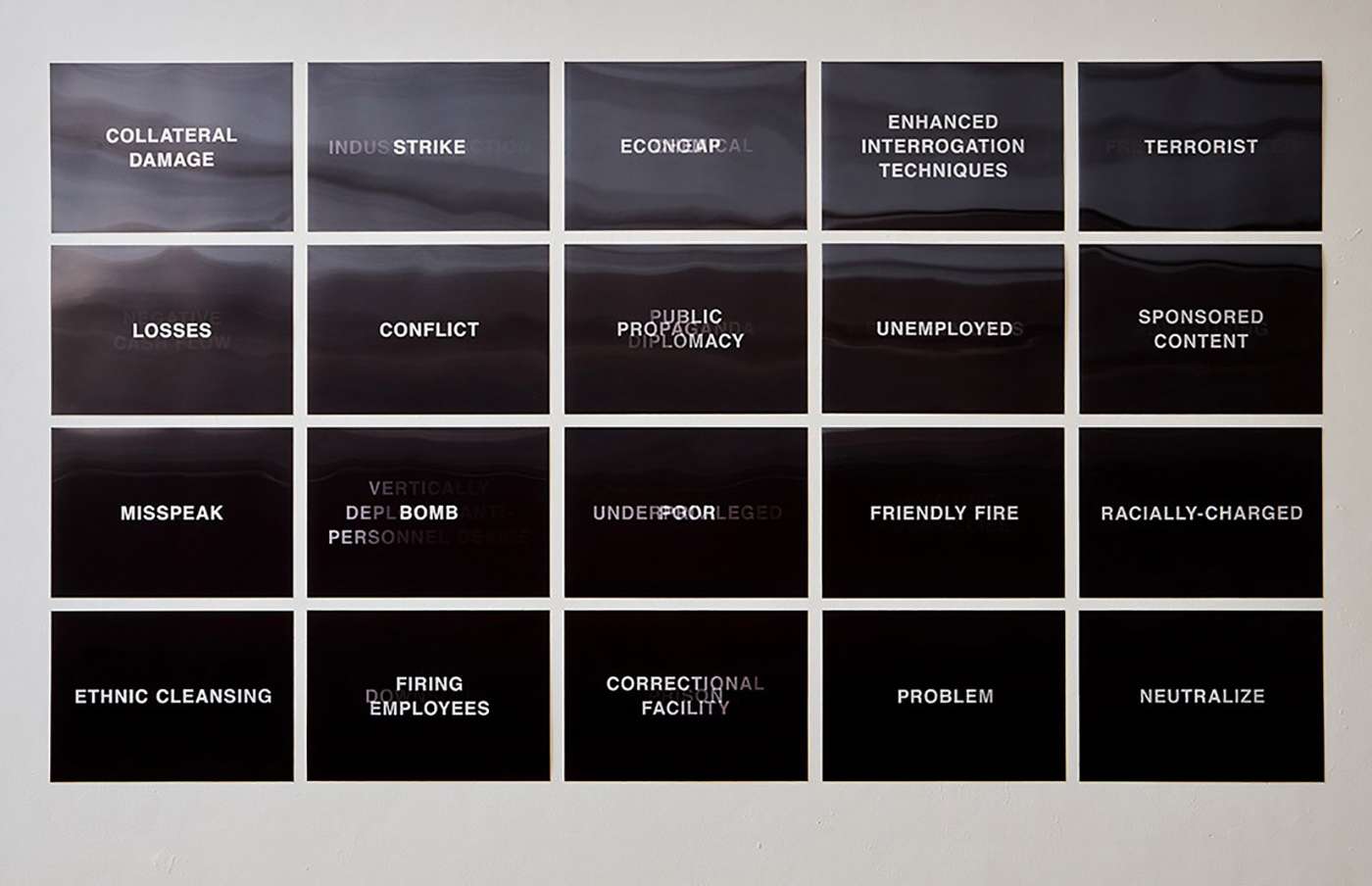

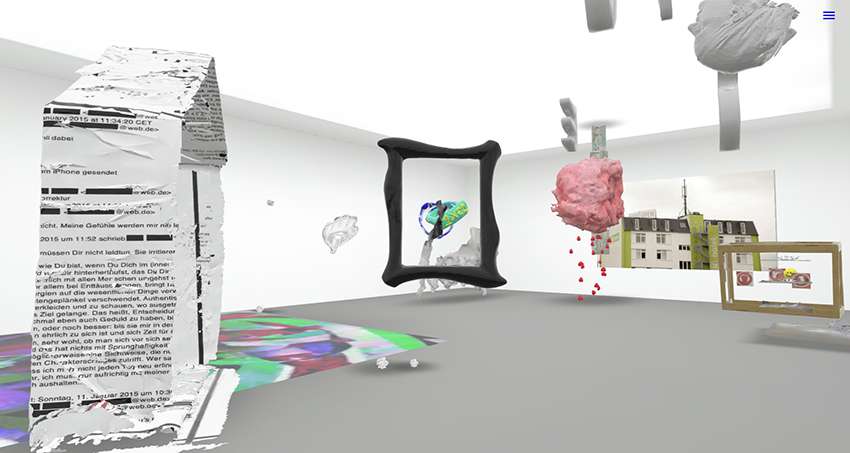

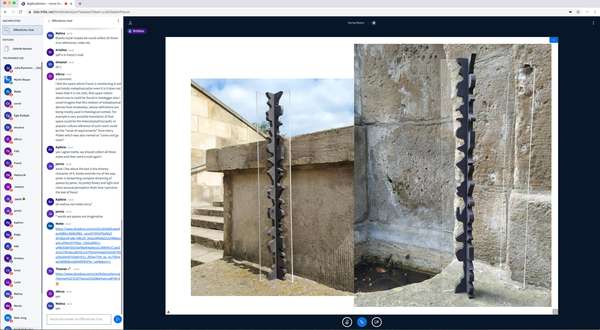

AN: There is also a less positive side of non-knowledge that is very relevant today, especially if we look at digital culture, and the new developments of data collection, big data and aspects of automatization. There is simultaneous growth of knowledge and non-knowledge. On one hand live with an abundance of knowledge, but at the same time there are mechanisms of control that hide data from us or hide the mechanisms themselves. The same mechanisms also force us into states where we have less control or no control. I think it is extremely important for artists and image producers to try to get behind those structures of control in order to gain knowledge of who is programming our new worlds, especially in order to create alternatives. Our digital society also forces us to behave more and more predictably and controlled, which is why one could say there is also an urgent need for unpredictable behaviour and moments of loss of control. This project wants to explore if laughter or the moving image could create those moments, to help us off this predictable path, so to say. Another point with data collection is of course aspects of privacy, which is one of the central questions in the first video I am producing in the context of this project. In this work I am interested in how todays immersive and interactive virtual reality (VR) technologies are as much about collecting information about our movements and affects as they are about immersing us into a virtual world. Similar to cinema and other moving images VR-technologies not only show us a new world but simultaneously also control and regulate our impulses, emotions, and consciousness, which make it a technology with two sides – one that could open us up for control and manipulation, but that at the same time could expand ideas we have around the self, our bodies and perceptions of reality.

Lf.: In the English translation Bataille talks about the laughable. He does not talk about comedy or humour.

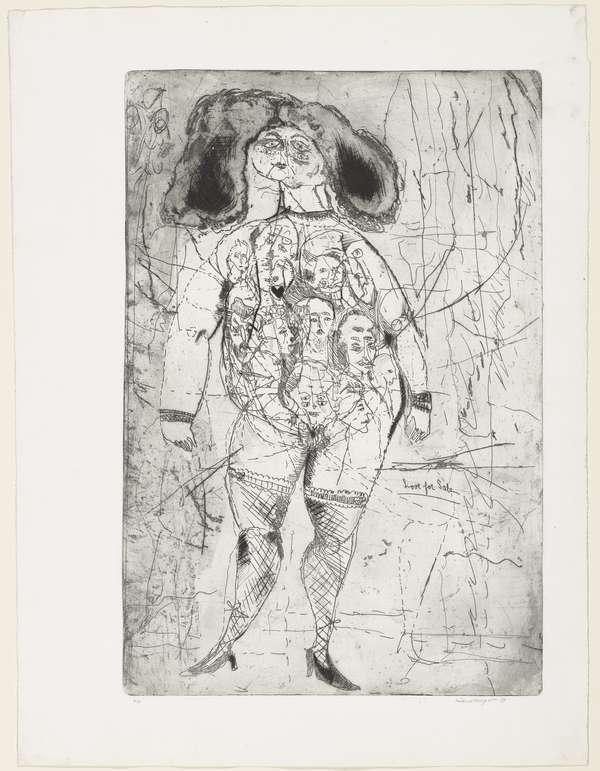

AN: Exactly. He rather connects laughter with trance, eroticism, trauma, shock and intoxication and those transgressive states where we are both ourselves and also leave ourselves, which I am also very interested in. What is this force that we laugh when we do not want to laugh, that comes from our self and that we cannot fully tame, even though we try to? If you study the history of laughter, our ideas about the laughing body have in many ways made a journey from something grotesque and untamed to a civilised smile. There is a whole parallel history to this that deals with what is included and what is excluded, what is part of us and part of the other, in our conception about ourselves and in society. Laughter has also a close link to failure, uncertainty, and ambiguousness, which makes it interesting for this project.

Lf.: You also talk about the laughing body. What is it? What makes the laughing body special and why should we be interested in this right now?

AN: For me the laughing body is the speaking body, an unpredictable force we have within. And as I mentioned before this becomes even more important in the digital world today, where algorithms predict and define our next steps based on what we have done so far. The laughing body is resisting that prediction. It also laughs at our own internal predicting machine – our brain, our reason and at ourselves in our attempt to be “homo seriosus” and to the fact that knowledge is speculation. But laughter has not only one side, which can also be seen in how it has been discussed by different philosophers. Adorno for instance was connecting laughter to the culture industry and the tranquilization of people, while other philosophers have seen it as a force that can turn around established systems or as a truthsayer. And if you look at totalitarian regimes, often the first things that are forbidden are jokes and laughter, as if they fear the truth would come out.

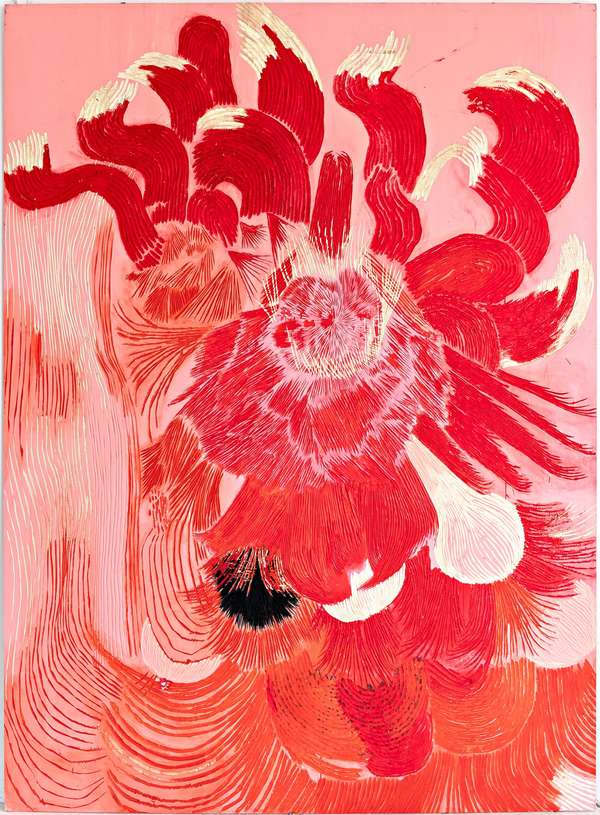

Lf.: How do you see your own artistic practice in this triangular of non-knowledge, laughing and moving image? Do you combine all these approaches?

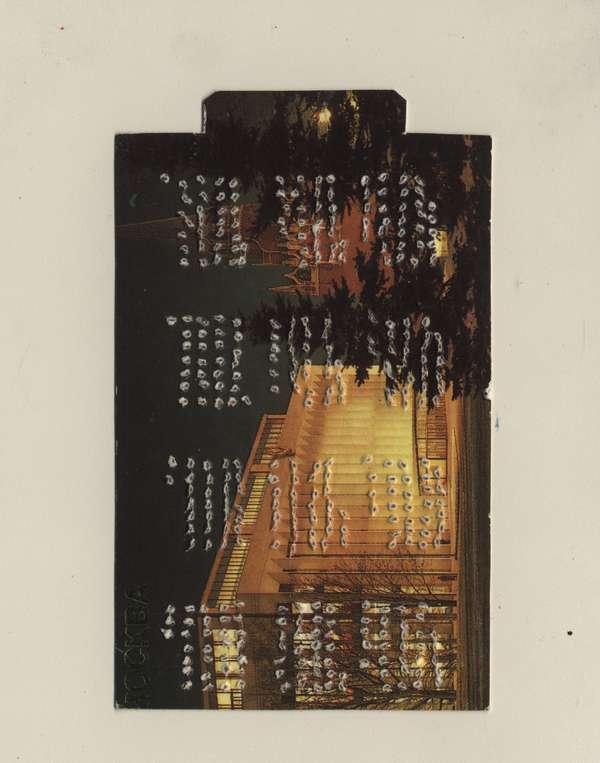

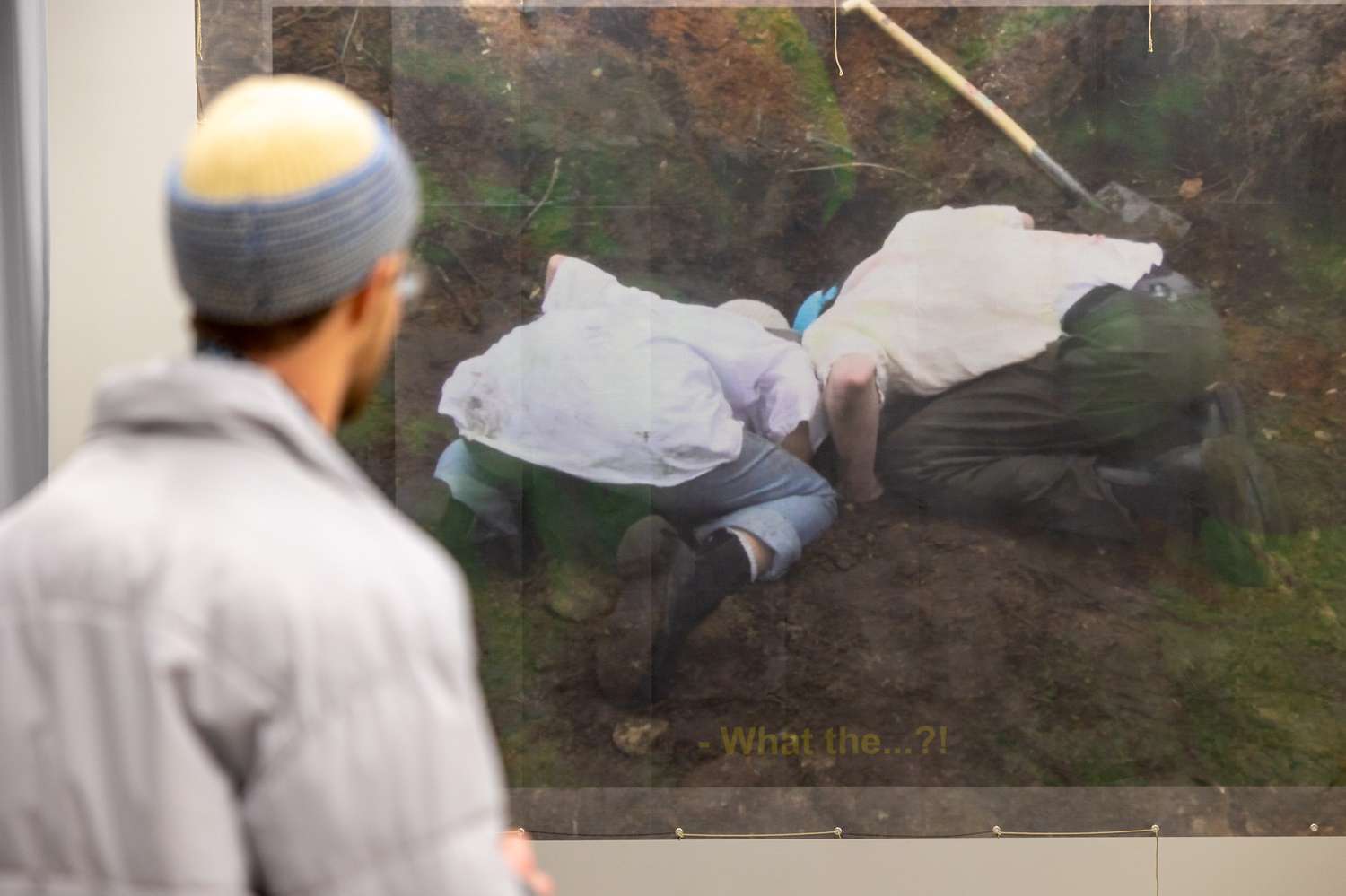

AN: For me they all stand in close relation to my artistic practice. Perhaps first as separate interests, but their relationships and connections have become more and more visible to me throughout the years. In a majority of my films and videos, especially my early work, there is no spoken language. Instead the focus lies on gestures, gazes and the speaking body. My artistic practice has always shown scepticism to instrumental language and linear narration and been more interested in what the body could tell that words cannot. But perhaps a direct link to the research topic came with my film Blue that I started in 2010, which also contains many moments of uncontrollable laughter. The film is based on the novel Le Bleu du Ciel (Engl.: Blue of Noon) again by George Bataille, which can be described as a disoriented ride through Europe, through five different cities in 1934, the pre-fascist years. The main characters in the book seem to have lost control over their bodies and emotions, and they either sob, laugh or tremble uncontrollably. Upon reading this book I was struck by the many parallels it had to situations and states in contemporary Europe, so I started to look for found footage material that was posted online, with scenes connected to situations in the novel in an attempt to recreate the narrative. The footage that I found was on one hand dealing with the increasing nationalism and the current rise of xenophobia in Europe, but it was also very much a document of how the body reacts to capitalism, in many aspects bodies in a state of crisis. Here we can draw parallels to other situations, as in states of post-traumatic stress, where the body tells us about our experiences not through words but through gestures.

Lf.: In Blue you already referred to the current political situation in Europe and Germany when you talk about xenophobia, the rise of right wing politics. For me on the one hand non-knowledge is something moving, interesting, but in this current political situation I think it is almost more important to defend knowledge. Because there is so much non-knowledge, ignorance, the rise of the so called “post-truth politics”.

AN: You are right. I agree that the situation today is very complex and in many ways completely upside down, where former strategies of resistance are turning against themselves, as could be the case of non-knowledge and also laughter. However the project is equally interested in examining both sides – the positive as well as the negative aspects. So apart from exploring how the moving image and the laughing body can become agents for new thought, acts, and embodiment, it also sets out to explore a series of sub-questions such as: How is technology, science, and our economic and political situation changing the way we move, act and perceive things? And how does it affect our relation to images, to each other and to time and space? Who is in control of our vision? Who is deciding the way we see the world? Can these powers be challenged? With the current political situation and rise of xenophobia it might be important to return to what xenophobia actually means – the fear of the foreign. So on one hand we could also claim that the unsecure times we experience today lead us to an increasing fear for the unknown, which prevents us from being able to change and from gaining new knowledge.

Lf.: A lot of comedians, artists, political humourists or activists use laughing strategies as a form of protest, as a tool. But in the current political climate they have to re-think their own strategies because real politics resemble a humorous theatre itself.

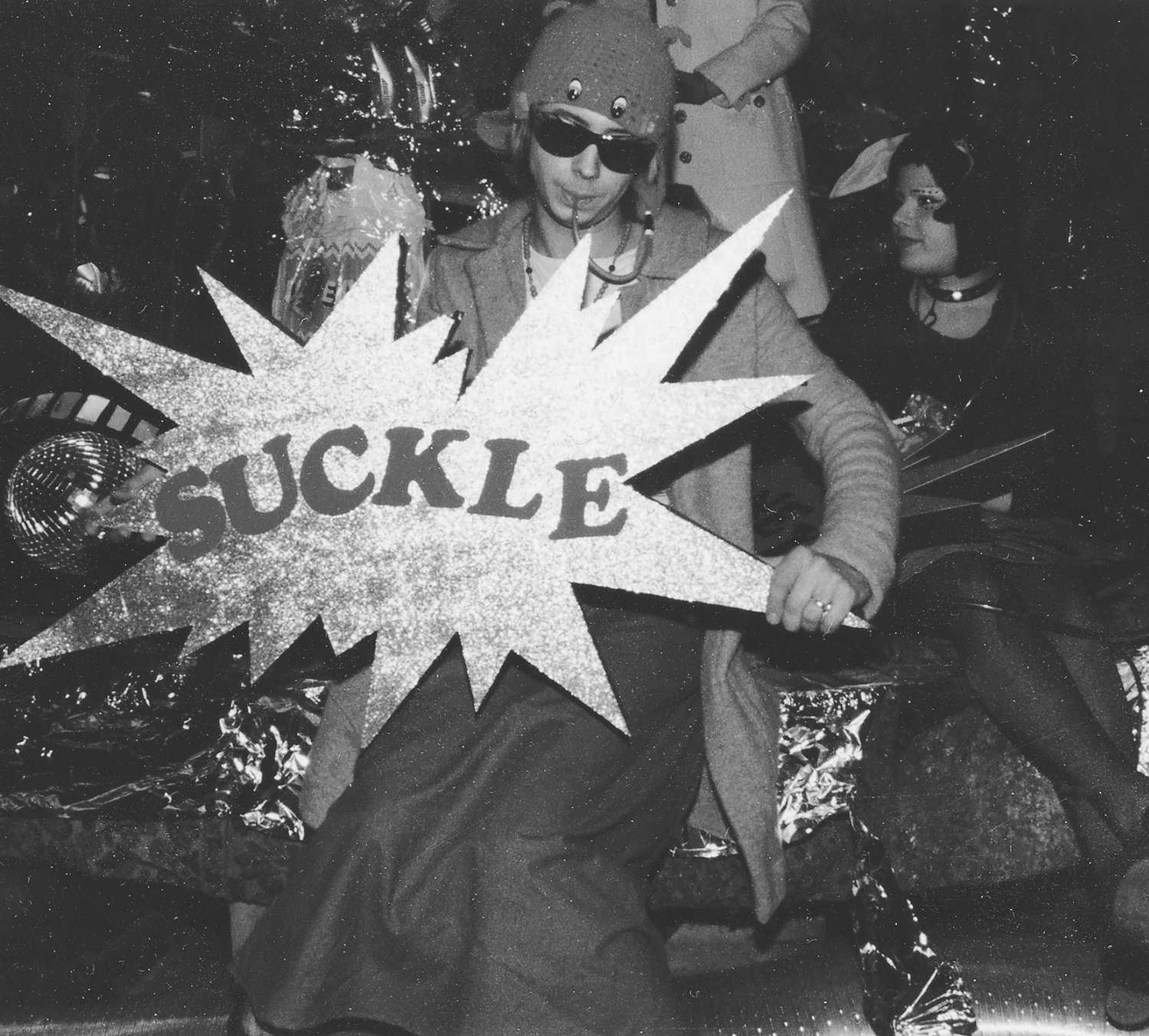

AN: Yes, the constant circulation of things makes especially humour very risky today. This is something that I also observed during the filming of my work The Discourse of the Drinkers in 2017, which is partly filmed in a queer bar in Neukölln in Berlin. What I noticed there was how this bar generated a safe space for a humour that was both free and ruthless, without being discriminating. However in a different context the same sentences could mean something completely different and suddenly harm more than produce something good. So today it is more difficult to know where and how you can act, as everything can constantly be put into a new context. This is a dilemma that also concerns my early works. My intention was to bring in uncomfortable, low culture and circulating images into the then relatively stable context of the art institution. But as many of my early works today can be found circulating online, these works have also started to counter-act themselves. But perhaps this is also what is extremely interesting and exciting with an artwork, that is has this capacity to change, and to add a new meaning to the old, and that multiple meanings can co-exist. I find it as important to try to understand and discuss these mechanisms, as it is to recognize the fact that we are not in full control, and that these moving images can play tricks back on us, and that they have a life of their own, or many simultaneous lives at the same time. And in our relation to them we make them and they make us, and we look at them and they (or their creators) look at us. This movement forces us to keep redefining what an image is. I am very interested and excited about thinking about how we will look at images in the future. Will they have minds? Should they have rights? At the same time I am very concerned about the development of a few dominant players who are increasingly using the moving image as a tool for social control.

Lf.: What forms will your research project take? As a kick-off event you invited Ed Atkins for a lecture. What does his work have to do with your topic?

AN: Ed Atkins is interesting because he connects the digital sphere with the dead body and he asks questions around the body-less virtual space. For me, his works also inherit an interesting paradoxical quality. He has an interest for the digital image as a corpse, but at the same time he brings dust, biological and analogue things into this digitally cleaned programmed space, which also makes the images highly alive. He is also subverting the conventions of moving images and reflects on digital media and the fundamental changes it has brought about in our perception of images and our own selves, something this project is also interested in. In January I invited Dr Michael Gaebler, a brain and cognitive scientist who held a talk and discussion around VR and the brain. For me it is important not only to bring in people from the arts but people from different disciplines, to stimulate a discussion. For April I have invited another artist, Marianna Simnett, who will give a talk on her practice. Although the projects main aim is to explore the moving images as a form of experimental thinking, these talks and discussions serve as an important part which also arises from a longing I have had for creating contexts and discussions that expand and relate to my own artistic practice, situations where dialogue and exchange can take place. I guess that is also what has brought me to teaching.

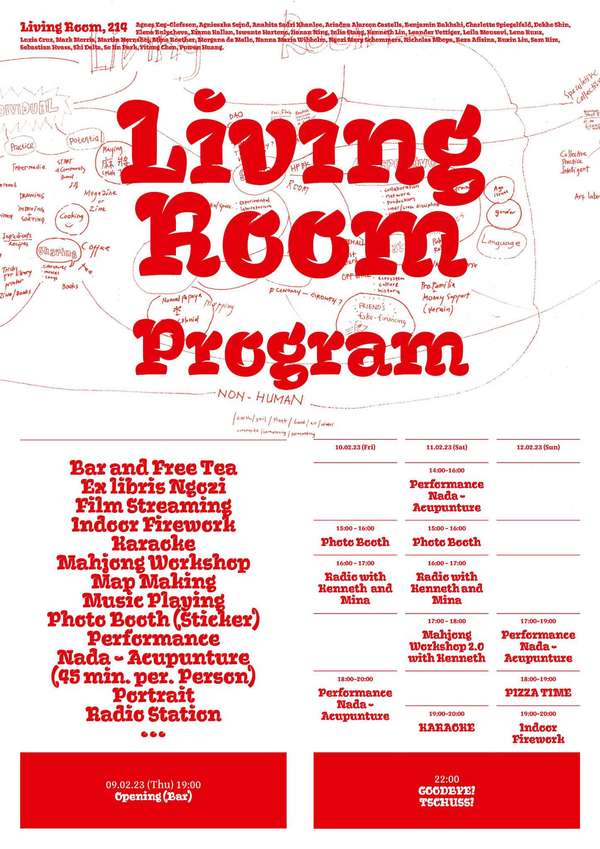

Lf.: Together with your students you initiated a series of events called “The Open Mouth”. Can this experiment also be seen in the context of your project?

AN: Yes, it is related but at the same time an independent series of events for time-based media works, a room for performance, music and the moving image. The idea has been to create a platform where the students can experiment and where the main focus lies on collaboration and socialisation. For the latest event in January we had invited all students to take part in an open stage event, so there were different contributions, planned as well as spontaneous, from all classes of HFBK Hamburg.

This interview was first published in Lerchenfeld #47.

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

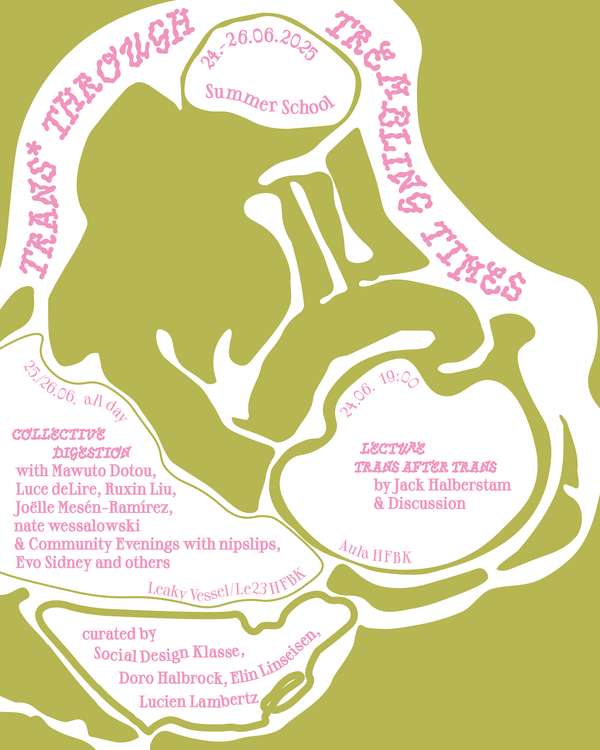

Lange Tage, viel Programm

Lange Tage, viel Programm

Cine*Ami*es

Cine*Ami*es

Redesign Democracy – Wettbewerb zur Wahlurne der demokratischen Zukunft

Redesign Democracy – Wettbewerb zur Wahlurne der demokratischen Zukunft

Kunst im öffentlichen Raum

Kunst im öffentlichen Raum

How to apply: Studium an der HFBK Hamburg

How to apply: Studium an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2025 an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2025 an der HFBK Hamburg

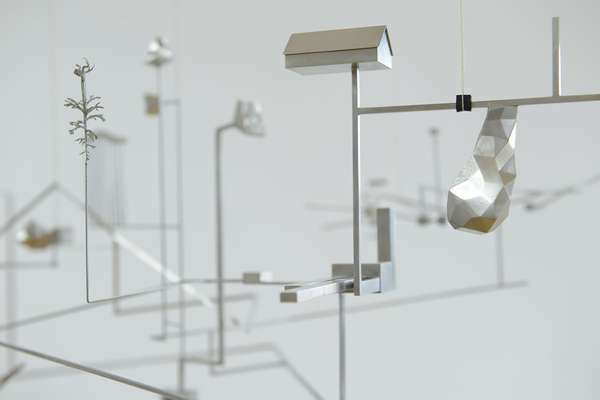

Der Elefant im Raum – Skulptur heute

Der Elefant im Raum – Skulptur heute

Hiscox Kunstpreis 2024

Hiscox Kunstpreis 2024

Die Neue Frau

Die Neue Frau

Promovieren an der HFBK Hamburg

Promovieren an der HFBK Hamburg

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Finkenwerder Kunstpreis 2024

Finkenwerder Kunstpreis 2024

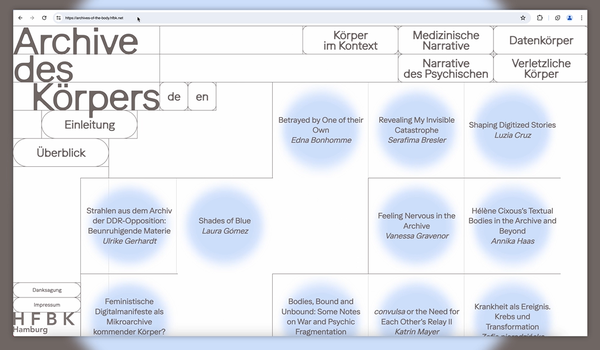

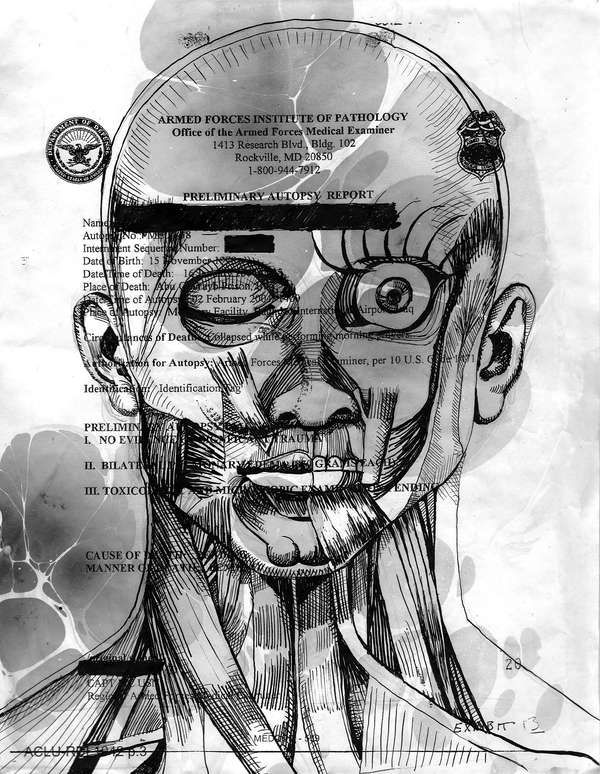

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

Neue Partnerschaft mit der School of Arts der University of Haifa

Neue Partnerschaft mit der School of Arts der University of Haifa

Jahresausstellung 2024 an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2024 an der HFBK Hamburg

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

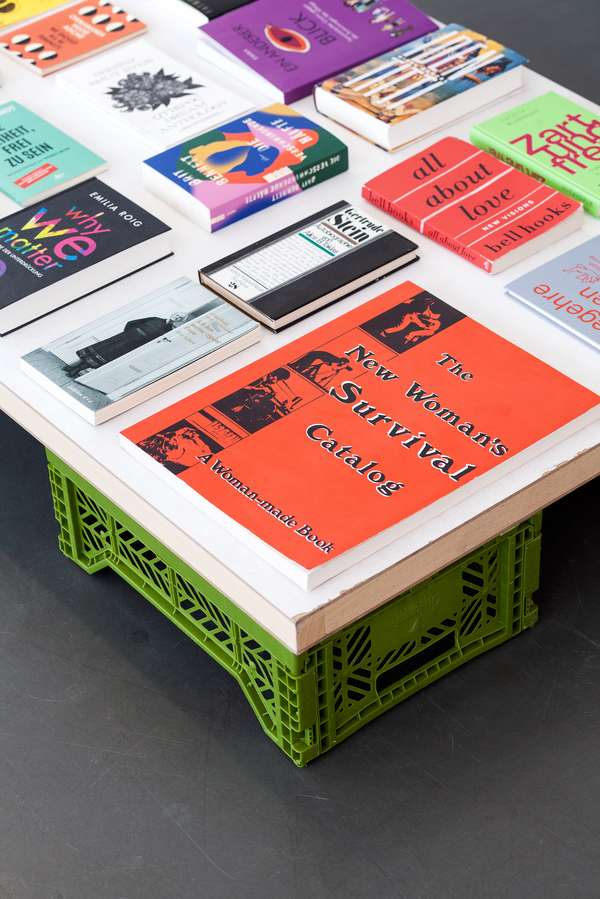

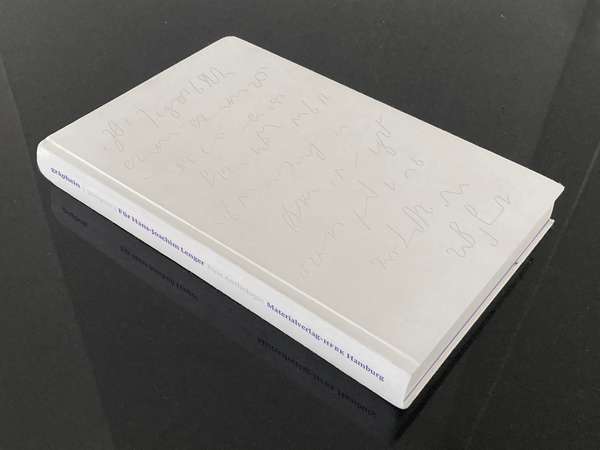

Extended Libraries

Extended Libraries

And Still I Rise

And Still I Rise

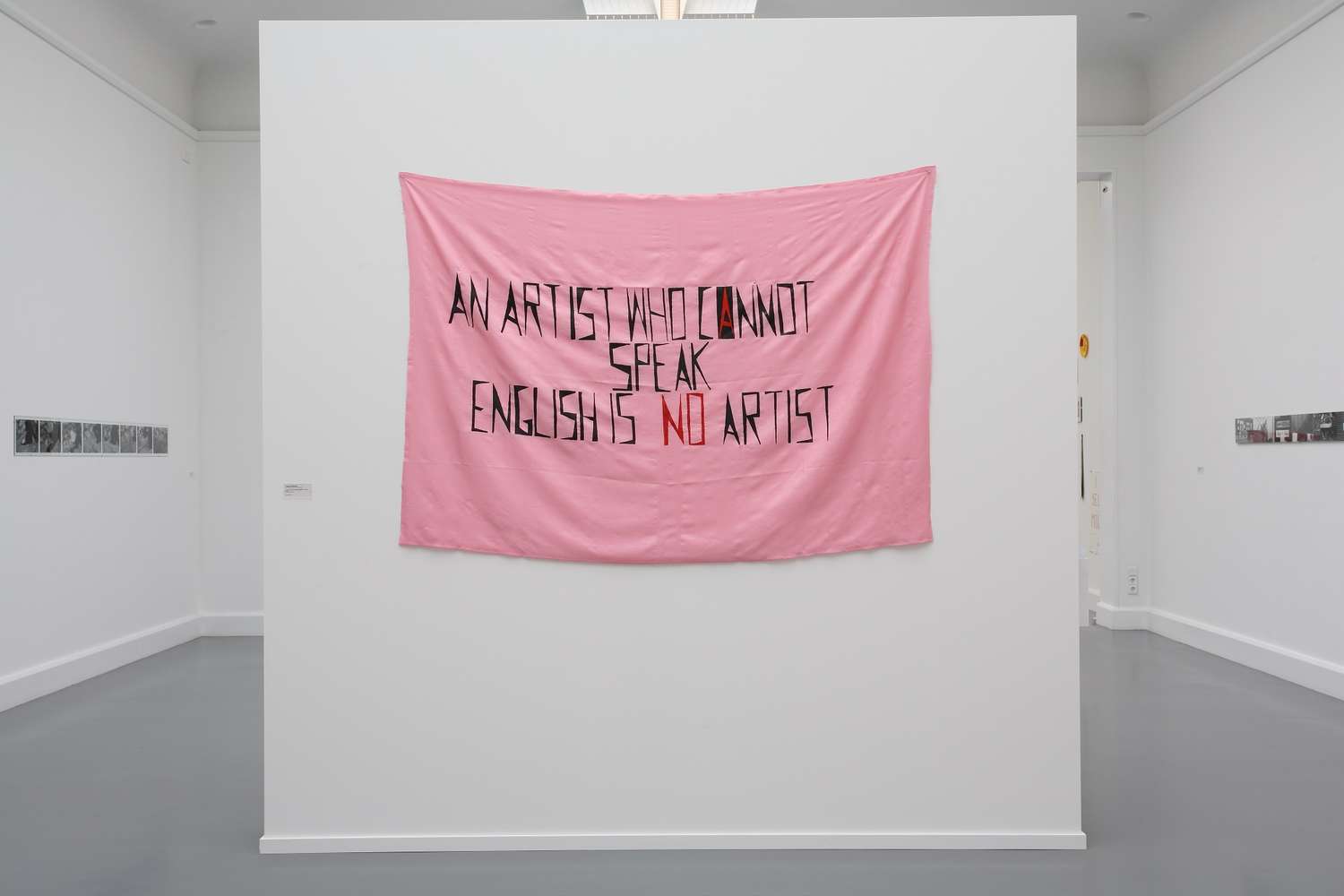

Let's talk about language

Let's talk about language

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

Let`s work together

Let`s work together

Jahresausstellung 2023 an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2023 an der HFBK Hamburg

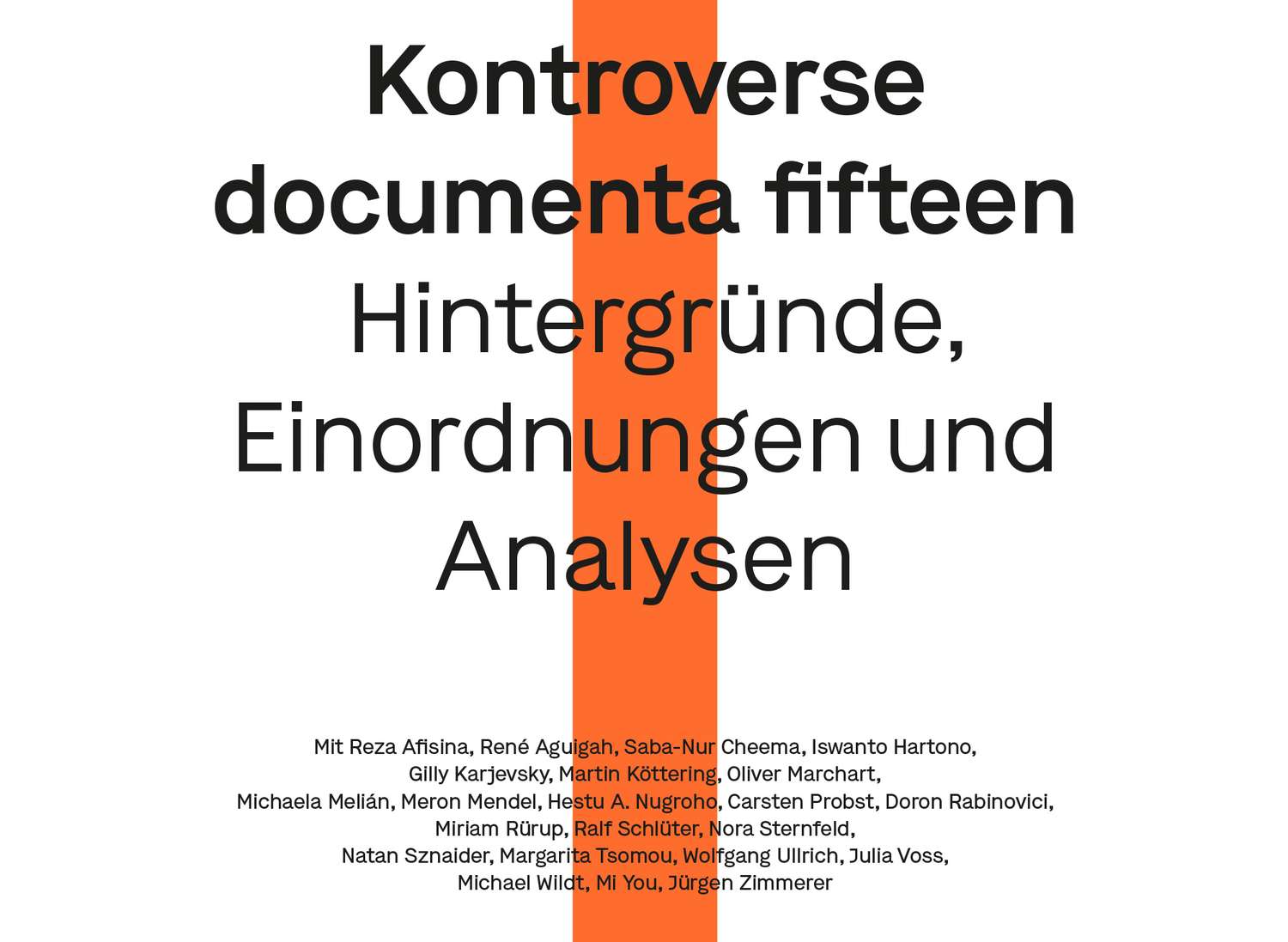

Symposium: Kontroverse documenta fifteen

Symposium: Kontroverse documenta fifteen

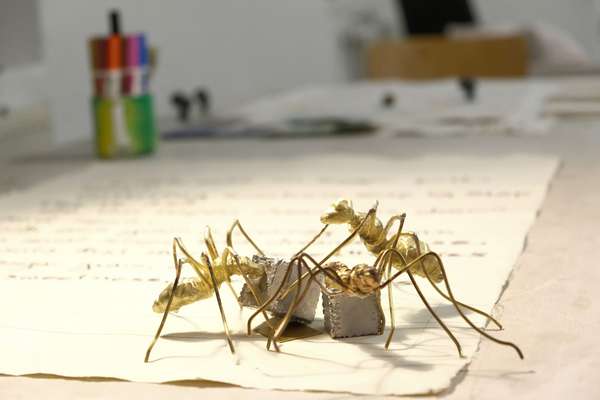

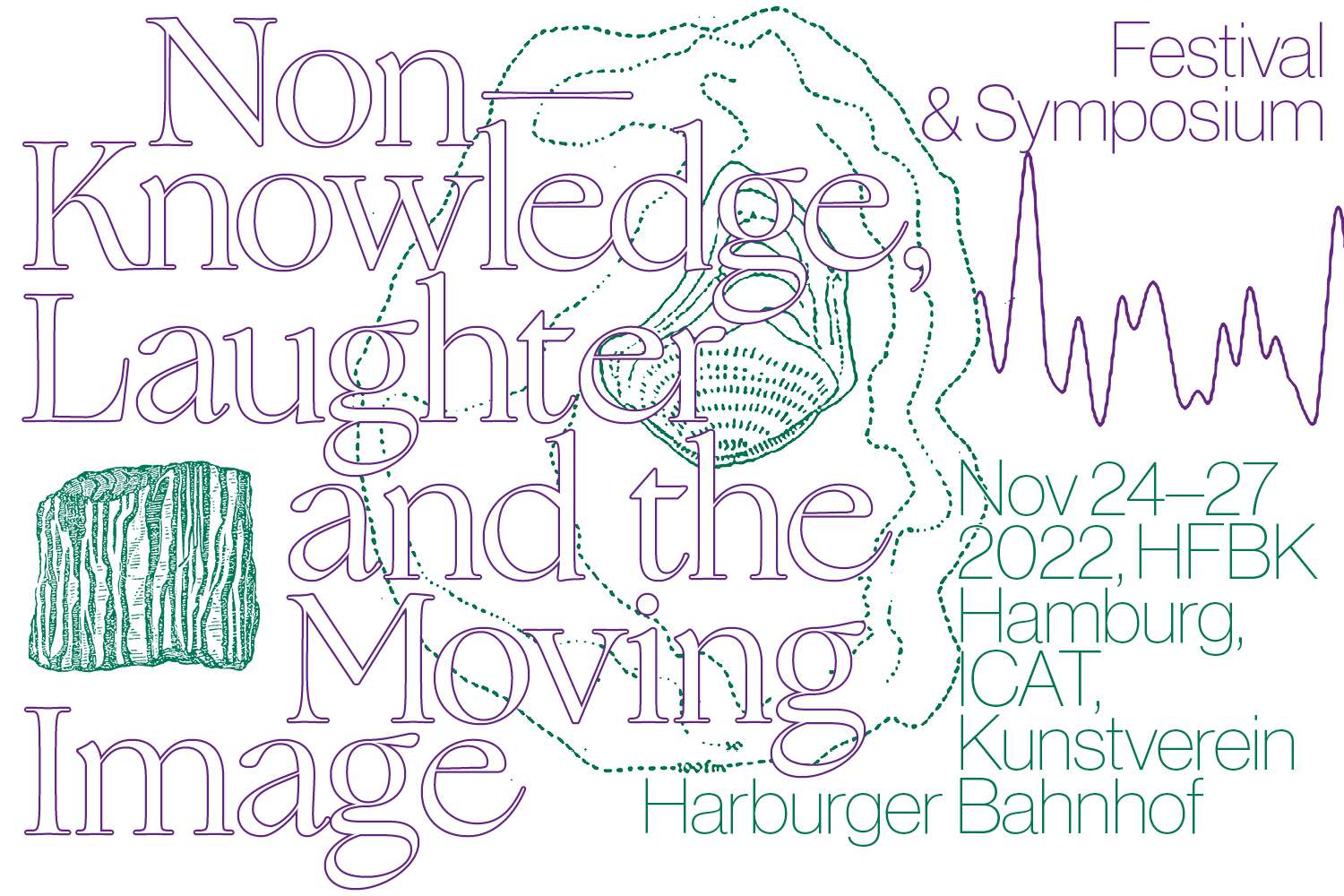

Festival und Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

Festival und Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

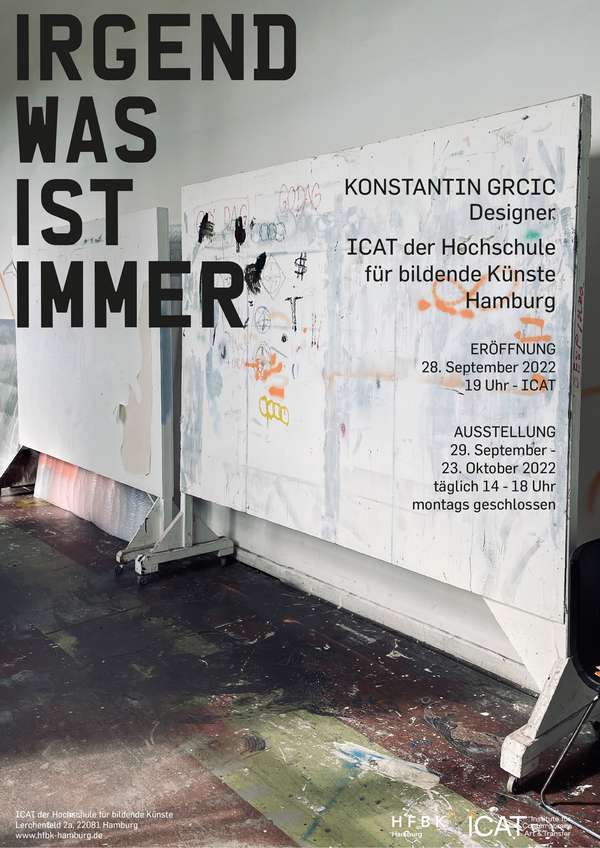

Einzelausstellung von Konstantin Grcic

Einzelausstellung von Konstantin Grcic

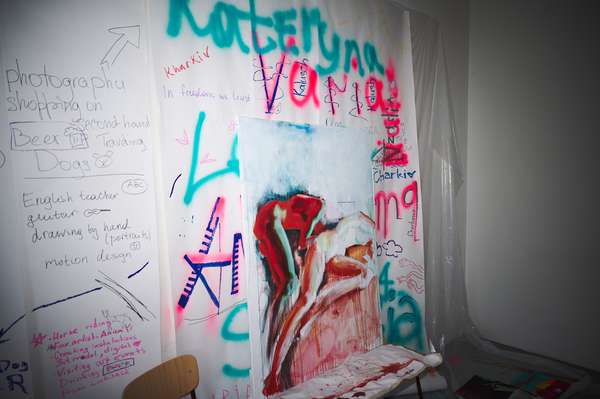

Kunst und Krieg

Kunst und Krieg

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

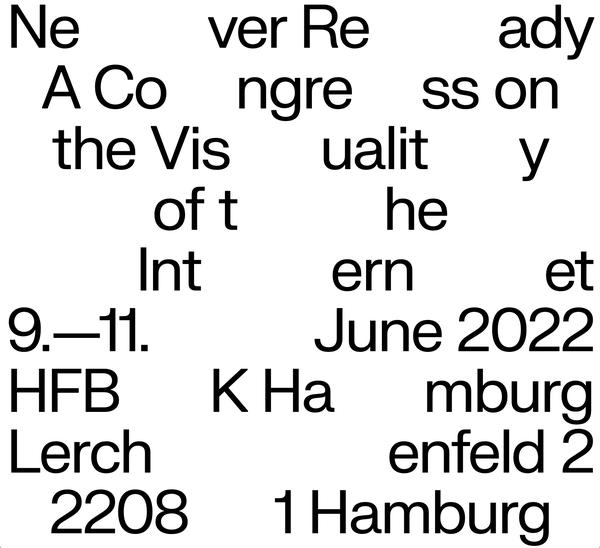

Der Juni lockt mit Kunst und Theorie

Der Juni lockt mit Kunst und Theorie

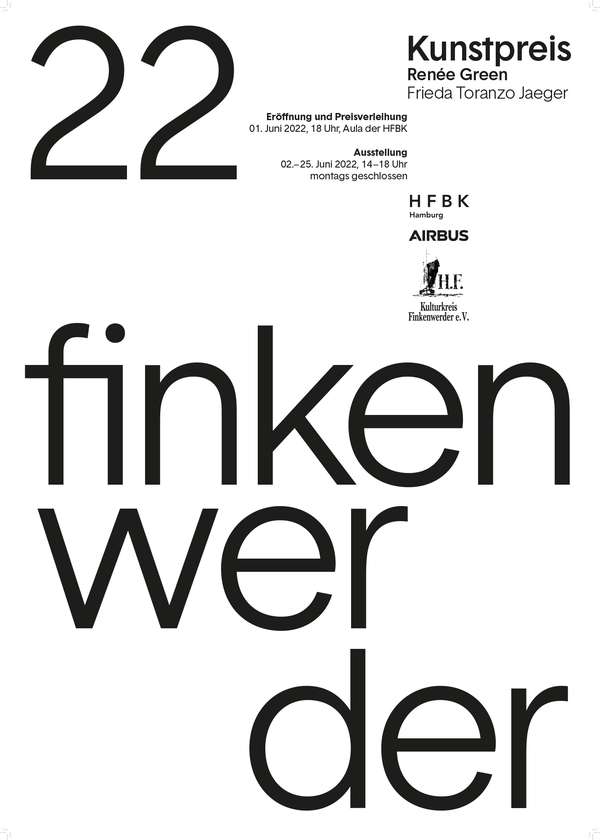

Finkenwerder Kunstpreis 2022

Finkenwerder Kunstpreis 2022

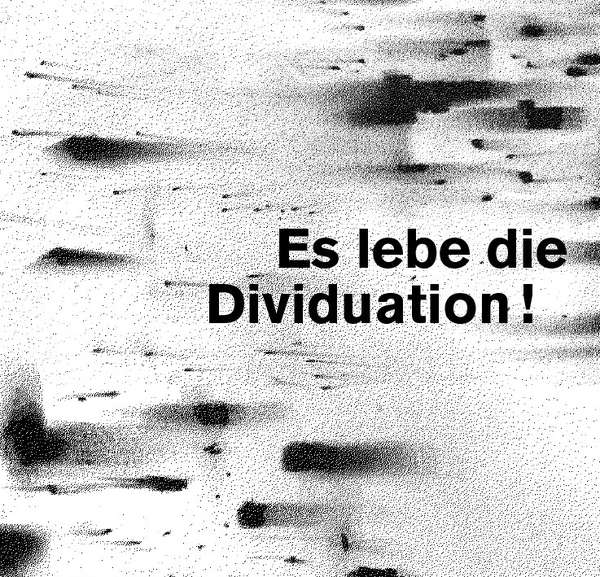

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Raum für die Kunst

Raum für die Kunst

Jahresausstellung 2022 an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2022 an der HFBK Hamburg

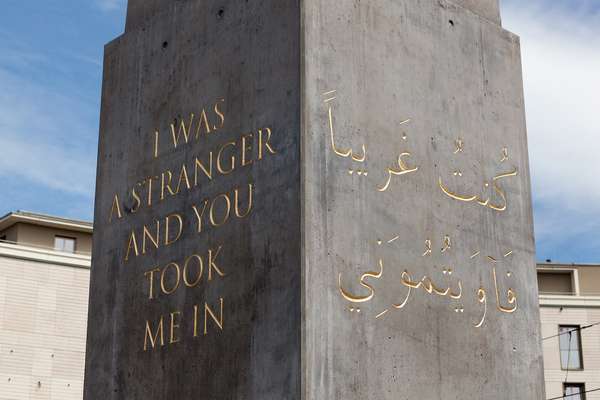

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments

Diversity

Diversity

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

Vermitteln und Verlernen: Wartenau Versammlungen

Vermitteln und Verlernen: Wartenau Versammlungen

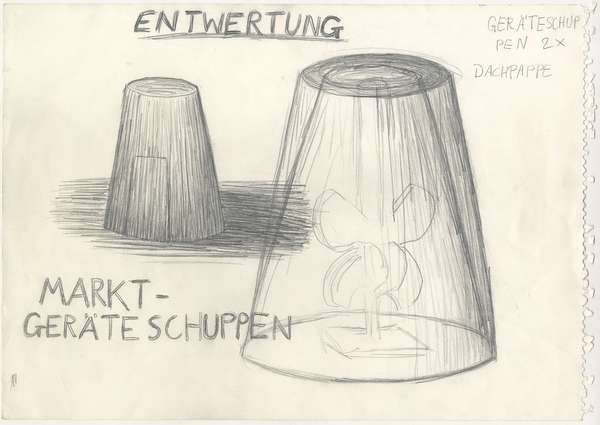

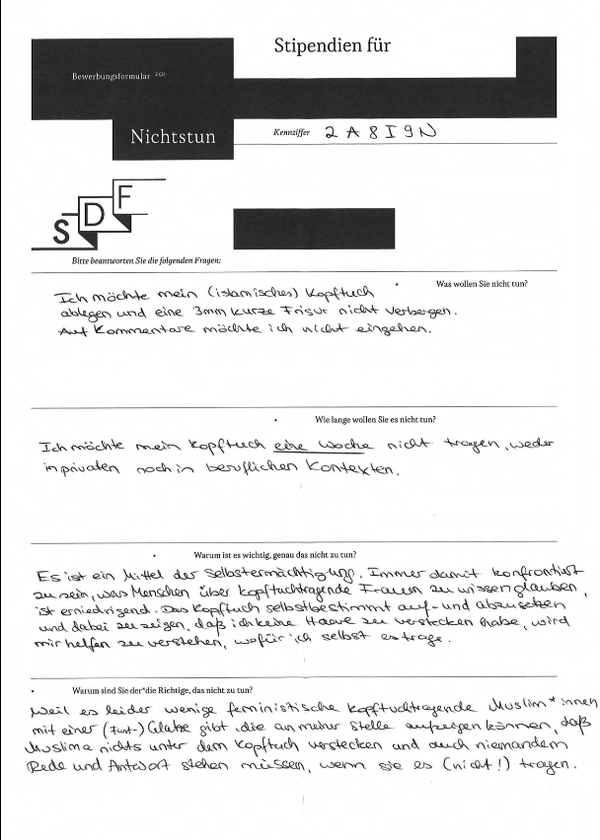

Schule der Folgenlosigkeit

Schule der Folgenlosigkeit

Jahresausstellung 2021 der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2021 der HFBK Hamburg

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

Digitale Lehre an der HFBK

Digitale Lehre an der HFBK

Absolvent*innenstudie der HFBK

Absolvent*innenstudie der HFBK

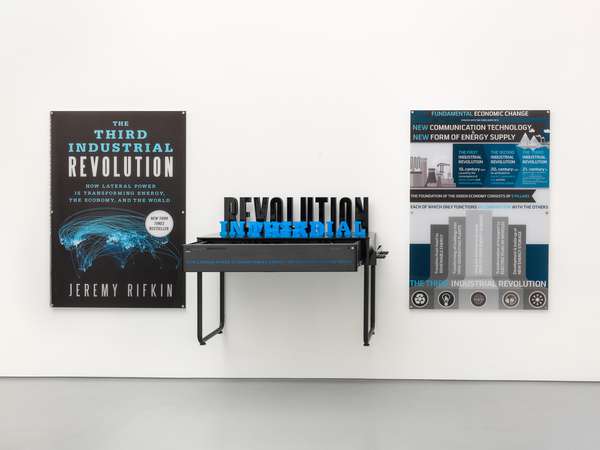

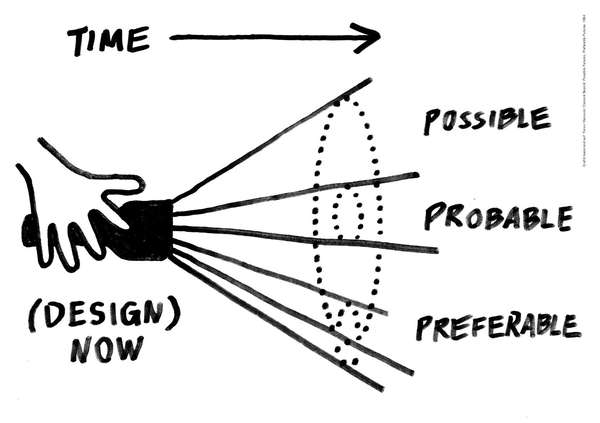

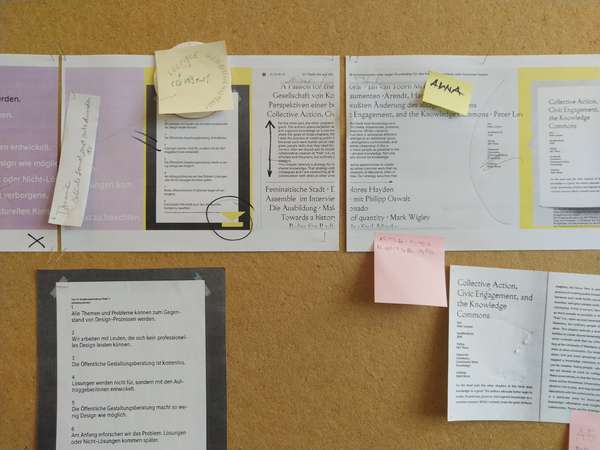

Wie politisch ist Social Design?

Wie politisch ist Social Design?