Counter-Memorials and Para-Monument

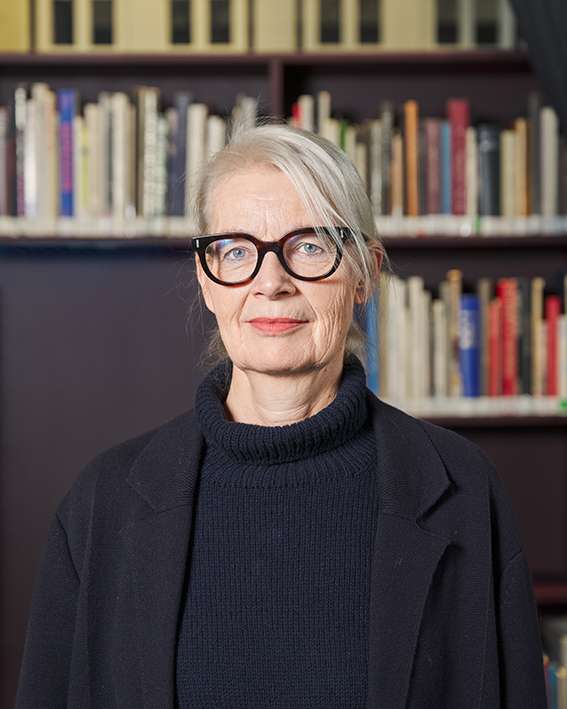

Nora Sternfeld.

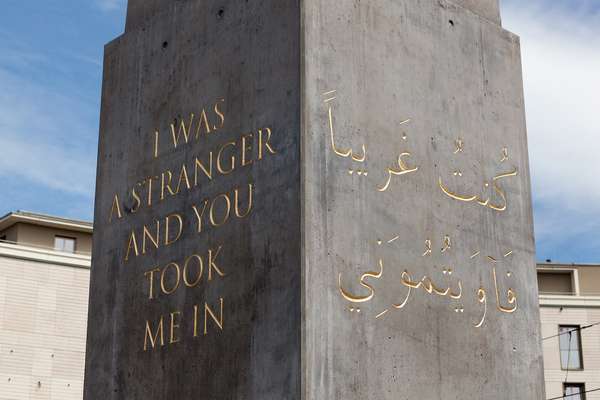

“I was a stranger and you took me in. Ich kam als ein Fremdling und ihr habt mich beherbergt.” A quotation from the Bible in four languages (Arabic, English, German, and Turkish) on a 16.3-meter-high obelisk stood during documenta 14 in the middle of Königsplatz in downtown Kassel. The work in question was produced for documenta and entitled Das Fremdlinge und Flüchtlinge Monument by artist Olu Oguibe. Both the Bible and the shape of the obelisk develop over-determined meanings. Olu Oguibe won the City of Kassel’s Arnold-Bode-Preis for this artwork. On the cultural committee that had to decide whether the obelisk would remain on Kassel’s Königplatz, Thomas Materner, Kassel municipal councillor for the AfD party, described the obelisk as “ideologically polarizing, distorted art”. He announced protests against it. The newspaper Hessisch Niedersächsische Allgemeine reported he had also said: “In his experience, the citizens’ anger over the obelisk was great”.[2] Not only the word “distorted” but also the talk of the anger of the citizens brought to mind echoes of the history of the November pogroms in Germany when the Reich Ministry of Propaganda insisted on the wording “the people’s anger” at a press conference.

What shape can artistic memory take if it has once again become possible to publicly denounce art as being “distorted” and “abhorrent”, [3] while at the same time everyone talks about a “never again” of which it has long since become unclear what this means? And what does this mean for a culture of remembrance that had to be fiercely fought for until into the 1980s, only for it to become reflexive in the 1990s and in the noughties to actually become a tourism factor – while at the same time being right-wing is once again stylish, possible, and powerful. So, what is a monument as a place of remembrance in a neoliberal world that is in many places becoming increasingly fascist? This essay outlines the history of artistic counter-monuments and explores the idea of para-monuments for the present.

Wrestled memories

An attempt to reconstruct the history/histories of remembrance cultures in the successor states of Nazi-Germany offers us insights into a contested terrain. For a very long time, monuments and memorials to support an admonishing memory of the Nazis’ mass crimes were by no means a matter of course in West Germany, in Austria, and in East Germany. Many decades after the liberation, in the successor states of Nazi-Germany the burden of remembering the Holocaust thus lay with the survivors and their relatives. For example, Sonja Klenk writes that “It was the survivors who directly after the end of the war erected commemorative plaques and memorials, whereby in the course of the following decades these fell into ruin and were forgotten.”[4] In this context, art started taking the Nazis’ crimes as subject matter for aesthetic enquiry as early as 1945. This was driven by the largely marginalized self-organization of the survivors. Taking as their motto “Never Forget”, survivor organizations dedicated themselves continuously to remembrance projects. On April 11, 1951, for example, a rally was held by the KZ-Verband on Morzinplatz in Vienna, the place where the Gestapo prison and the former Hotel Metropol had stood. In this context, a memorial stone to the victims of the Gestapo was designed and consecrated by the Opferverband (Association of Victims) without official authorization, in other words illegally. Not until the 1980s was the Arbeitsgemeinschaft der KZ-Verbände und Widerstandskämpfer Österreichs able to unveil the new memorial to the victims of violent oppression by the Nazis. “The nascent aesthetics of commemoration is usually driven by a monolithic and block-like formal idiom and figurative symbolism of suffering: The battle for remembrance is expressed in modernist monuments that take the sheer fact of survival as their subject matter, lend material form to mourning the murdered, commemorate the persecuted as individuals, and seek to express the victory of Modernity. In other words, initially it was about taking a stance as a gesture by the survivors and that stance was not infrequently bound up with struggles over the history of politics.”[5] Remembrance had to be fought for if it was to be won.

Counter-Monuments

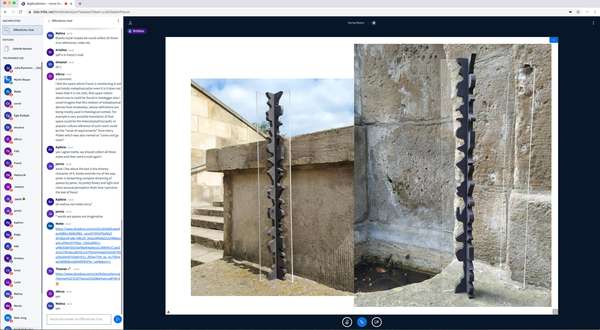

While this took a lot longer in Austria and remains controversial to this day, in West Germany in the 1980s (in the wake of the US TV series Holocaust having been broadcast on the ARD channel in 1979) a new, almost omnipresent self-reflexive debate on the Nazi crimes ensued in art in public spaces. For example, James Edward Young wrote in 1992: “Germany’s ongoing Denkmal-Arbeit simultaneously displaces and constitutes the object of memory.”[6]. In this context, he coined the term “counter-monument, which he found exemplified above all by the practice of Jochen and Esther Shalev Gerz, while also referencing Horst Hoheisel, and in their work saw a German memory against itself”. A key role in these projects for counter-memory was that they did not wish to pre-empt any debate or create a monumental presence in its stead. In other words, instead of substituting the debate people should be having, the idea was to ensure the wound was not allowed to heal and the debate kept going. This resulted in artistic/formal strategies ranging from presence to absence: In this context, the best-known example is the Harburg Memorial Against Fascism, War, and Violence – for Peace and Human Rights by Jochen Gerz and Esther Shalev-Gerz. When erected in 1986 it consisted of a 12-meter-high stele that challenged passersby to write on it and thus participate in remembrance, and as part of this to help gradually lower the column into the ground. We can read on a panel in seven languages, and the panel remains the visible trace of the column which has since disappeared into the ground: “We invite the citizens of Harburg and visitors to the town to add their names here to ours. In doing so, we commit ourselves to remain vigilant. As more and more names cover this 12-meter-tall lead column, it will gradually be lowered into the ground. One day, it will have disappeared completely and the site of the Harburg monument against fascism will be empty. In the end, it is only we ourselves who can rise up against injustice.”[7]

In 1987, artist Horst Hoheisel created a memorial for documenta 8. It, too, refused to create closure for remembrance simply by reconstructing something or providing a classic monument, and instead sought to keep memory open and thus highlight that there can never be any closure. The result was a memorial as negative: Hoheisel’s piece references a fountain with an obelisk – a 12-meter-high, 12-step pyramid sculpture made of sandstone that stood in front of the Kassel City Hall. Nazi activists had, as part of a pogrom on April 9, 1939, destroyed what they had decried as a “Jewish fountain”. It had been donated in 1908 by Kassel burgher Sigmund Aschrott on the occasion of the new-build City Hall being inaugurated and had been designed by the same architect, Karl Roth. Hoheisel’s counter-monument consisted of “sinking the fountain as an inverted shape into the ground on the forecourt outside the City Hall. In this way, the pyramid became a funnel into which the fountain’s water cascaded loudly. The symmetrical opposite of the original fountain reached down as far as the water table and thus became a symbol of the rupture, the absence that had arisen and which could no longer be filled.”[8]

What has happened since

While this critical debate was increasingly occupying public space in West Germany during the 1980s, global politics was changing. After German Reunification, the remembrance projects were as good as the pre-eminent theme presented by the country. In the noughties, a certain sense of pathos of negative remembrance was transformed into a tourist attraction that definitely fostered a specific identity and completely overwrote the discourse on remembrance in East Germany – which had most certainly also been problematic and inadequate as regards tackling anti-Semitism. In the course of this, the East German notion of “anti-fascism” was actually delegitimized. Such a smoothing over of negative memories in the noughties are symbolized best by the “topography” and the “stele”. In the booming tourism metropolis of Berlin, where rents seem to go up by the month and an ever-increasing number of districts are experiencing gentrification, remembrance became an overall urban project. “The concrete of the blocks in the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe may perhaps quote the above-mentioned Modernist gesture of the survivors, but here concrete also becomes the stylistic material of a new German “pride in remembrance”, and the omnipresent “stele” of the noughties becomes its prime form.”[9] In the noughties, remembrance started to forge an identity not just for Germany, but also for Europe. Enzo Traverso thus pointed to the danger of the culture of history becoming depoliticized as a consequence. In his opinion this “does not involve forgetting the Shoah but rather an abuse of memories of it, enveloping it in balm, locking it away in museums, and neutralizing its critical potential, or, worse still, using it apologetically as the support for the current world order.”[10] So what should a counter-monument do if it is the counter-monuments themselves that are now fostering identity? And what to do if the “culture of remembrance” tends to assist the emergence of the New Right rather than causing an outcry at it happening?

Kassel’s Königsplatz is located a few hundred meters from the venue of the former Aschrottbrunnen fountain. It was there that from summer 2017 until fall 2018 an obelisk once again stood – the documenta art work by Olu Oguibe that was then derided as “distorted art”. It may be a conscious strategy to get people accustomed to hearing these words echo. And in the context of the documenta, that is as ironic as it is bitter[11]: After all, since its first edition back in 1955 the documenta has repeatedly presented itself publicly with the function of drawing on an artistic practice that was ostracized for being “degenerate”.[12] The fact that a fountain stood like an open wound in front of the City Hall changed nothing as regards the stance of the AfD or the way the debate on the obelisk took place in the city. The irony and scandal of the repetition of the right-wing threat to an obelisk in downtown Kassel went unnoticed.

Para-Monument

Now, Olu Oguibe’s defamed artwork is formally anything but a counter-monument. It does not try and duck the eye, dares to tower up into public space as an obelisk, to occupy Königsplatz. I suggest Olu Oguibe’s Das Fremdlinge und Flüchtlinge Monument be read as re-appropriation. Indeed, in relation to German “counter-monuments” I would term it a para-monument. It does not address the idea of a monument negatively but appropriates the form and discourse of the powerful monuments in order to turn these properties against them. This complicated relationship that is neither completely against the monument nor completely defined by it can best be described by the prefix “para”. After all, the Greek prefix παρά means both “from… to, near, next… to, toward… along” (spatially speaking) as well as “during, along” (temporally) and metaphorically “compared to, unlike, counter to, against”. In the Greek, the emphasis here is on the deviation and not on the contrasting opposition. It is nevertheless the prefix that in Latin becomes “contra”.

What we find in Oguibe’s monument is thus the sediment of the Bible’s violence and colonialism, in the course of which hundreds of obelisks were erected in the colonized cities of this world. However, in this instance the obelisk is not meant to admonish but is rather appropriated in terms of a dimension intrinsic to it and is now aimed at the violence of Christendom and colonialism as well as against the violence of the European border regime and racist discourses in Europe. Oguibe makes use of the phallic shape of the obelisk, a shape that initially arrived in France as a result of its violent expropriation, where it then became the insignia of power in the colonial districts. Oguibe turns this around and uses the massive object as a call for action. What if it were the obelisk itself that were to declare the sentence written on it? For the colonial obelisks most certainly arrived in the cities in which they stand as strangers. And evidently many of them stand there intact to this day.

As a practice that operates both in the midst of the sediments of monumental histories of violence and over and above them, I read Oguibe’s obelisk as a massive and concrete form of (re-)appropriation. The para-monument is thus not an anti-monument. Rather, it is the uncanny practice that seeks to bring to life the ghosts of the sedimented conflicts and histories of violence. The para-monument does not refuse to be monumental; however, it does refuse the refusal attributed to it, possibly by the critical art world and also by the latter’s critics.

Olu Oguibe’s para-monument became a venue where people assembled in downtown Kassel: Each day, its plinth was used by young people and passersby. They sat on it, read, tapped away on their smartphones, and occasionally started chatting with one another. The para-monument on Königsplatz thus had performative traits: Each day, it acted out its inscription, displayed the slogan’s innate irony when it looked as though it would not be able to stay; it invited people to use it, to meet in front of it, became the trigger for a political conflict that was paradigmatic for the political situation in Germany in 2018.

And in actual fact the obelisk was not allowed to stay at Königsplatz. Precisely after two Neo-Nazi murders had taken place in Kassel – Halit Yozgat (1985-2006) and Walter Lübcke (1953-2019) were the two victims – it would have been a real symbol. Nevertheless, the municipal authorities took it down and moved it to Kassel’s Treppenstrasse – a venue on the route from the Fridericianum to Kulturbahnhof – which is a central location for the documenta in Kassel and easier to market in the context of the “documenta mile”. It is, however, less heterogeneously frequented and therefore evidently simply seemed opportune. There, the obelisk returned to having a more monumental function and exudes the flair of contemporary art at a place where it is less of an irritant.

Etymologically speaking, the term monument derives from the Latin word “monere” (remain, admonish, warn, refer to). This relates, on the one hand, to the past, and, on the other, to the future. In other words, with monuments the focus is, as it were, on the meaning of remembrance. And this brings us back to the problems that we could have with the notion of the ‘monumental’. On the one hand, the meaning of remembrance is itself a bone of contention. Monuments get appropriated and given a new meaning. And, on the other, the pathos of meaning its itself problematic. Hannah Arendt already gave things a perspective when speaking of the “perfect meaninglessness”[13] of the Shoah and warning against assuming the Nazis’ crimes had meaning or assigning them such. However, when seeking an anti-fascist “we” and a “never again” we repeatedly stumble across this meaning. So, what would a monument be that neither instils nor assumes a meaning? Possibly one that faces up to the fact that history is something that is fought over.

[1] This essay is based on a lecture in the lecture series “[Counter-]Monuments. Practices of remembrance in the public space”, held by the Sculpture Projects Archive Research Group at the Institute of Art History at Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster during the 2018 summer semester, and on an essay that appeared in the catalog of artist Ernst Logar in 2018. Nora Sternfeld: “Gegendenkmal und Para-Monument. Politik und Erinnerung im öffentlichen Raum/Counter-Monument and Para-Monument. Politics and Remembrance in Public Space”, in: Ernst Logar (ed.): Ort der Unruhe/Place of Unrest, (Klagenfurt & Celovec: Drava, 2018), pp. 40-61.

[2] https://www.hna.de/kultur/documenta/documenta-kunstwerk-obelisk-afd-spricht-von-entstellter-kunst-8601756.html [Last visit: 09.11.2021].

[3] In January 2018 Austrian politician Gottfried Waldhäusl, a member of the FPO and Section Chairman in Lower Austria, spoke in connection with an intervention with a statue of St. Mary of “abhorrent art”, of dirty art, and of filthy art.

[4] Sonja Klenk, Gedenkstättenpädagogik an den Orten nationalsozialistischen Unrechts in der Region Freiburg-Offenburg, (Berlin, 2006), p. 8.

[5] Katharina Morawek & Nora Sternfeld, “Visuelle Geschichtspolitiken im öffentlichen Raum. Eine Reflexion über künstlerische Strategien der Erinnerung im Postnazismus,” https://www.linksnet.de/artikel/26432 [Last visit: 09.11.2021].

[6] James Edward Young, “Counter-Monuments. Memory against Itself in Germany Today,” in: Critical Inquiry, vol. 18, no. 2. (Winter, 1992), pp. 267-96, here p. 269.

[7] Harburger Mahnmal gegen Faschismus, https://kulturtag-harburg.netsamurai.de/harburger-mahnmal-gegen-faschismus/ [Last visit: 09.11.2021].

[8] Ibid.

[9] Katharina Morawek, Nora Sternfeld, Visuelle Geschichtspolitiken im öffentlichen Raum. Eine Reflexion über künstlerische Strategien der Erinnerung im Postnazismus, https://www.linksnet.de/artikel/26432 [Last visit: 09.11.2021].

[10] Enzo Traverso, Gebrauchsanleitungen für die Vergangenheit. Geschichte, Erinnerung, Politik, (Münster, 2007), p. 71.

[11] Another historical documenta piece was vandalized in 2018: Identitarian movement members stuck their hate stickers “Kein Fußbreit den Antideutschen” and “Good Night Left Side” on the label next to Thomas Schütte’s “Die Fremden”.

[12] The anti-Semitism innate in the “Degenerate Art” exhibition was not, however, the topic when in the 1950s the documenta, in opposition to Nazism, again sought to take up from the “ostracized” art as it was called back then. Rather, it was mainly works by non-Jewish artists that were rehabilitated in Germany, for instance by art historians such as Werner Haftmann, who had himself been a Nazi Party member. This appeared like a radical new beginning, an innocent Modernism, but merely masked Nazi continuities. Today, the talk is of ‘art-washing’ as regards the first documenta in 1955 – meaning a documenta myth that ensured one did not have to speak about the crimes or one’s own involvement in Nazism and its art and knowledge output and rather was able to present oneself as the victim, to over-identify with the real victims and place oneself in the genealogy of “ostracized art”.

[13] Hannah Arendt, “Die vollendete Sinnlosigkeit,” in: Nach Auschwitz, (Berlin, 1989), p. 29.

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

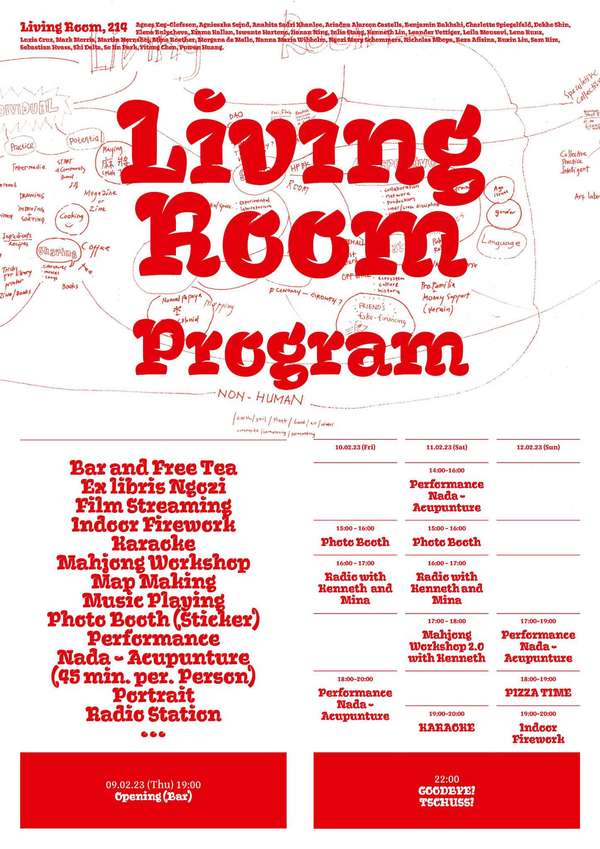

Long days, lots to do

Long days, lots to do

Cine*Ami*es

Cine*Ami*es

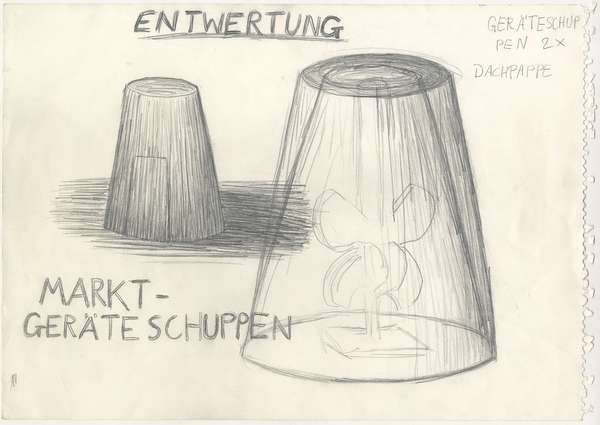

Redesign Democracy – competition for the ballot box of the democratic future

Redesign Democracy – competition for the ballot box of the democratic future

Art in public space

Art in public space

How to apply: study at HFBK Hamburg

How to apply: study at HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2025 at the HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2025 at the HFBK Hamburg

The Elephant in The Room – Sculpture today

The Elephant in The Room – Sculpture today

Hiscox Art Prize 2024

Hiscox Art Prize 2024

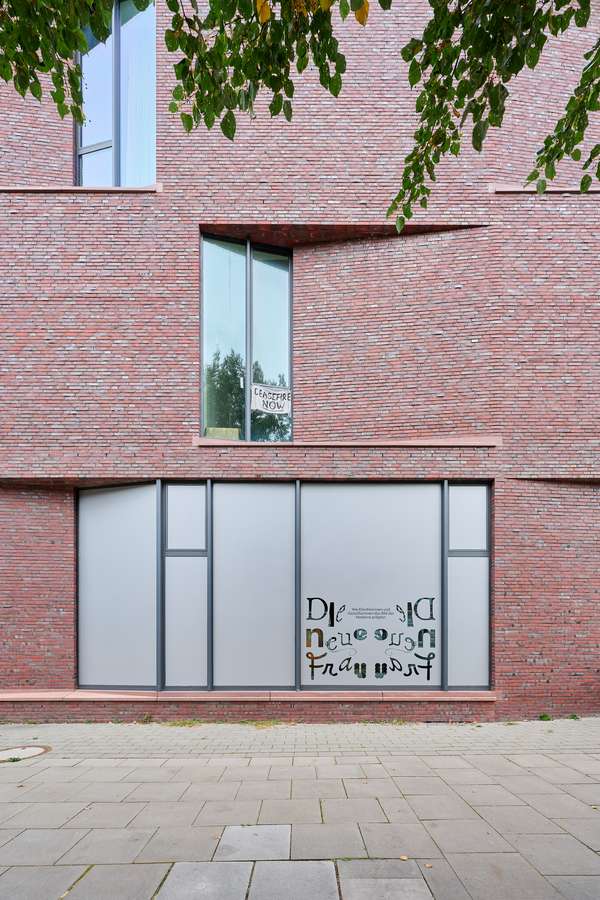

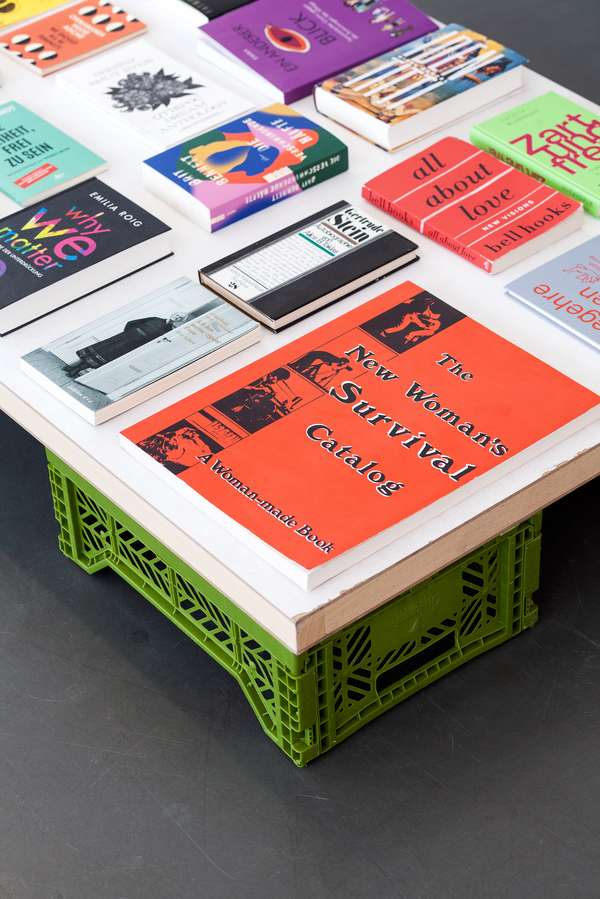

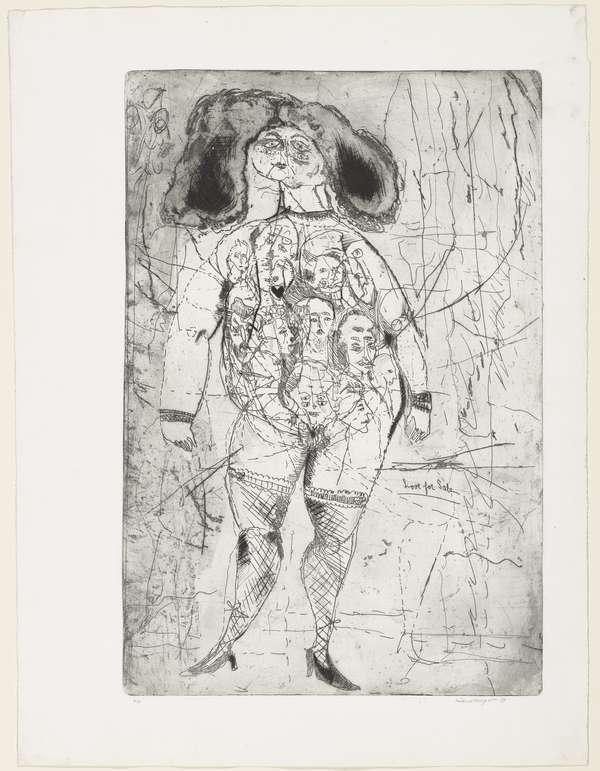

The New Woman

The New Woman

Doing a PhD at the HFBK Hamburg

Doing a PhD at the HFBK Hamburg

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2024

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2024

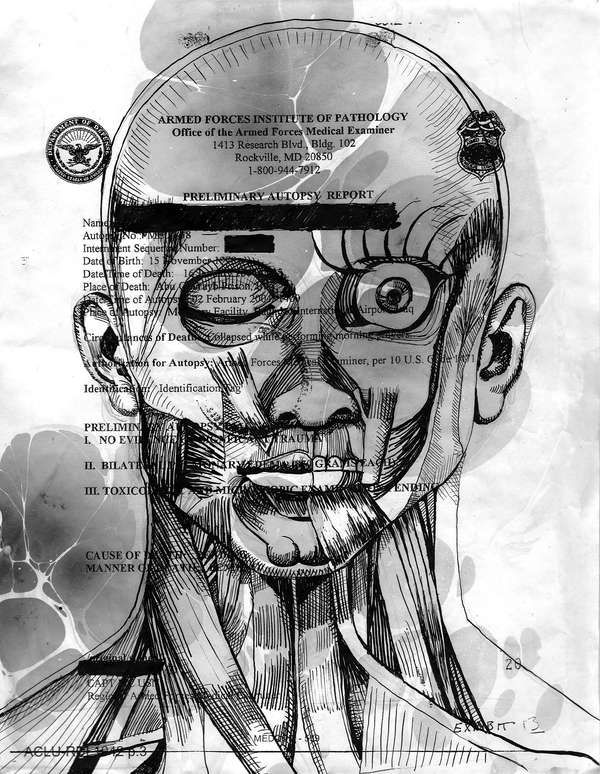

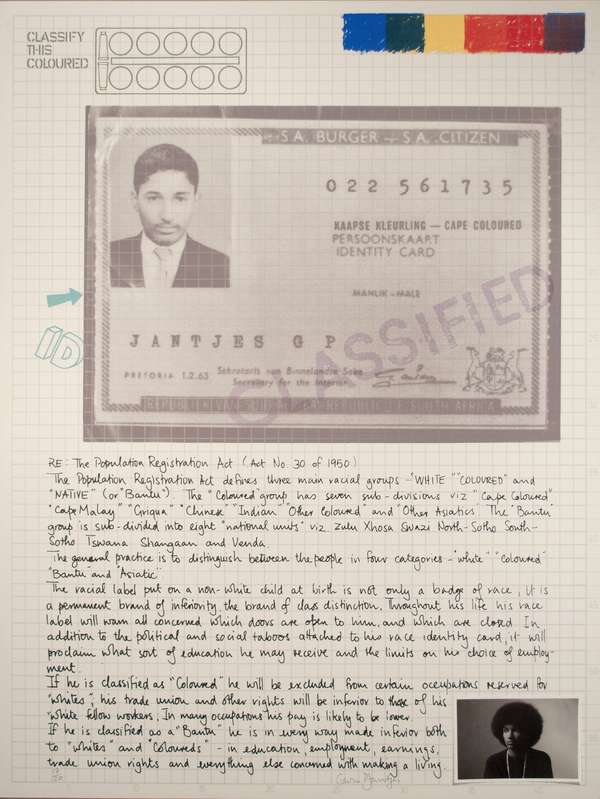

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

New partnership with the School of Arts at the University of Haifa

New partnership with the School of Arts at the University of Haifa

Annual Exhibition 2024 at the HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2024 at the HFBK Hamburg

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

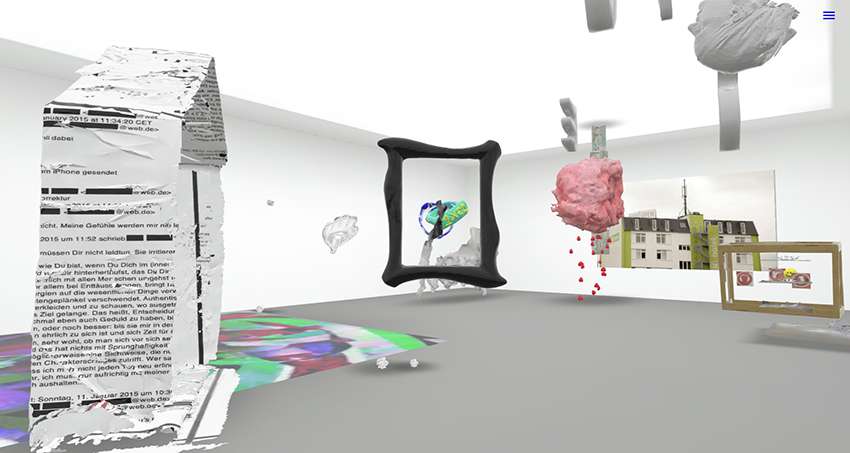

Extended Libraries

Extended Libraries

And Still I Rise

And Still I Rise

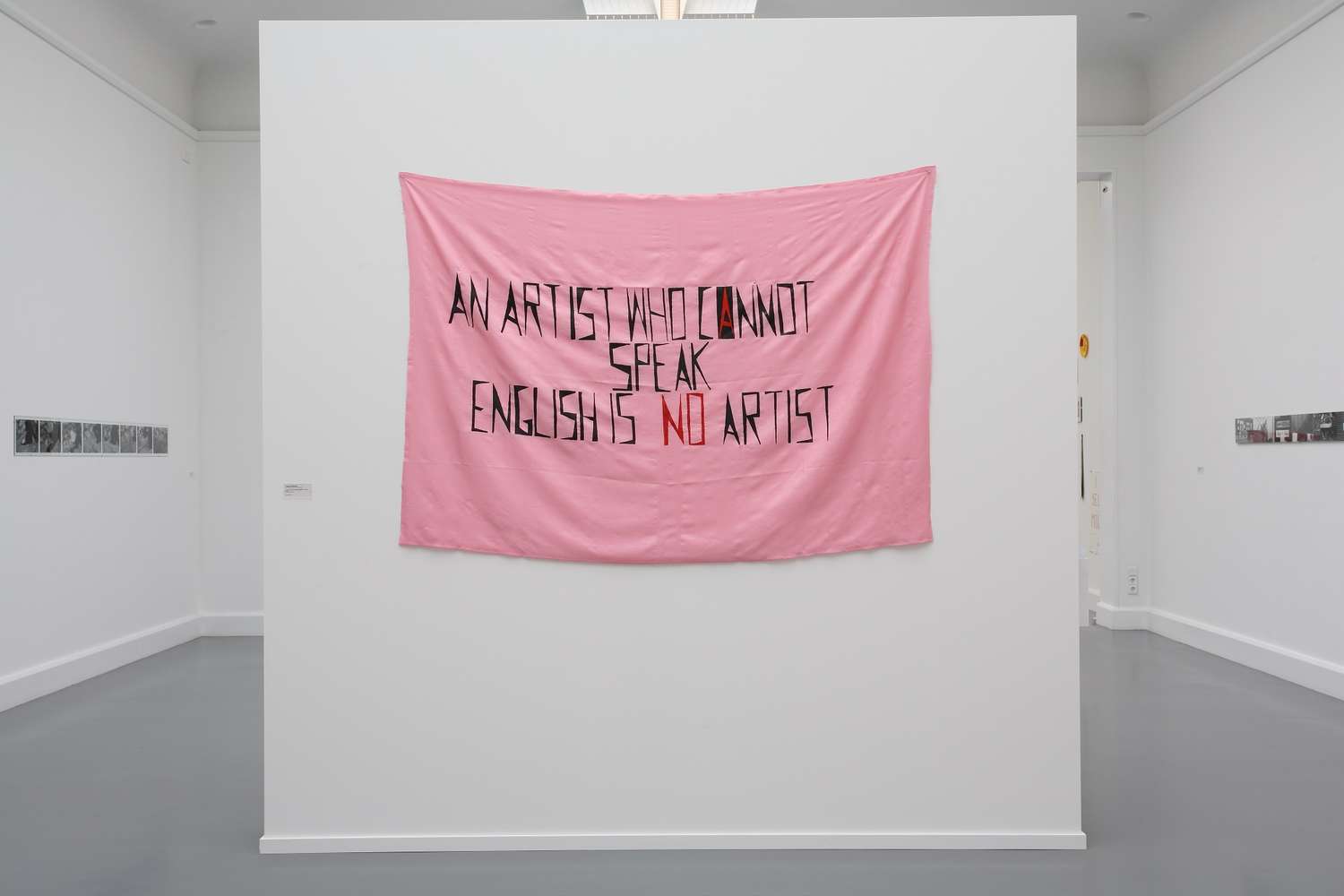

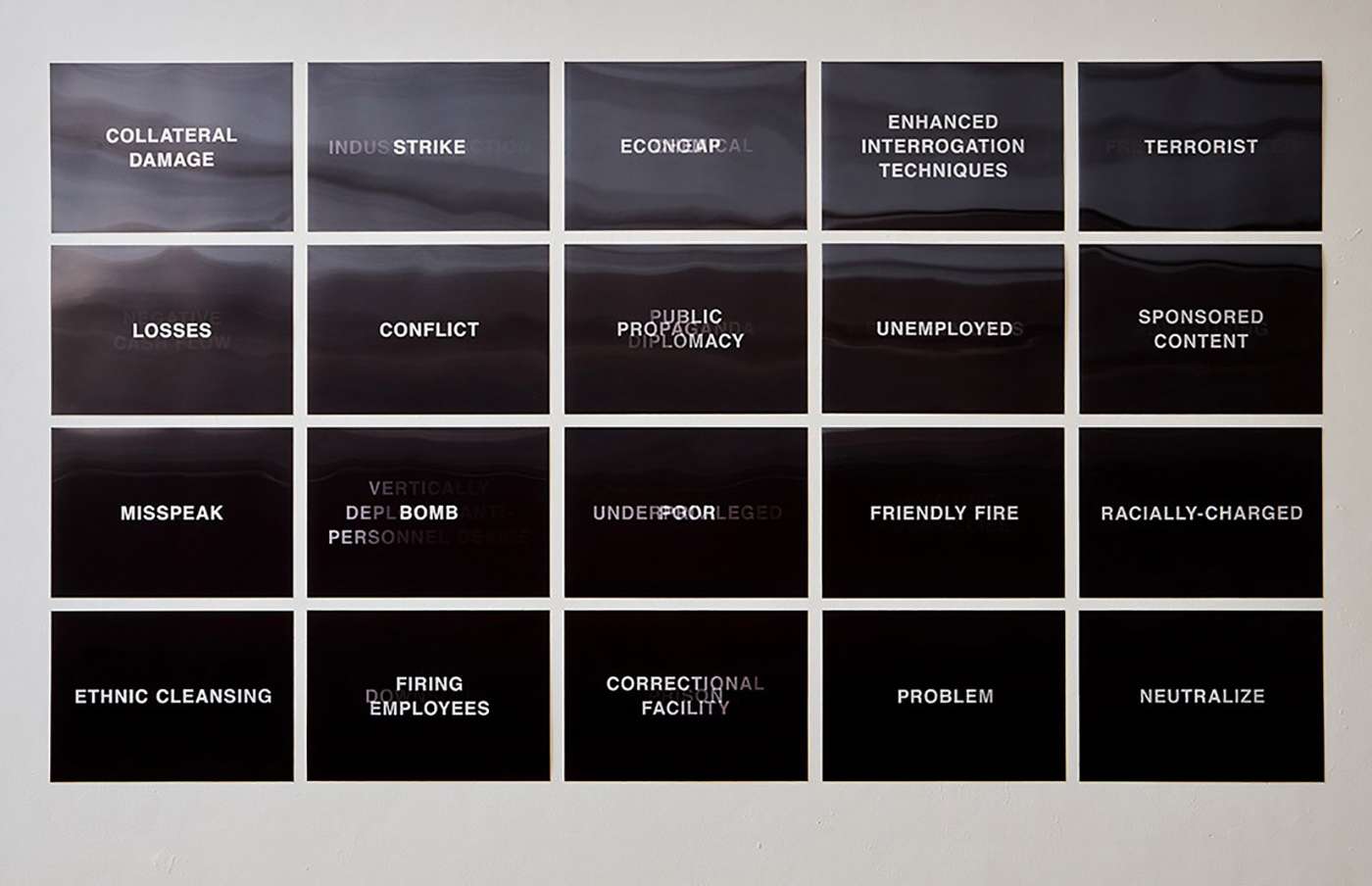

Let's talk about language

Let's talk about language

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

Let`s work together

Let`s work together

Annual Exhibition 2023 at HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2023 at HFBK Hamburg

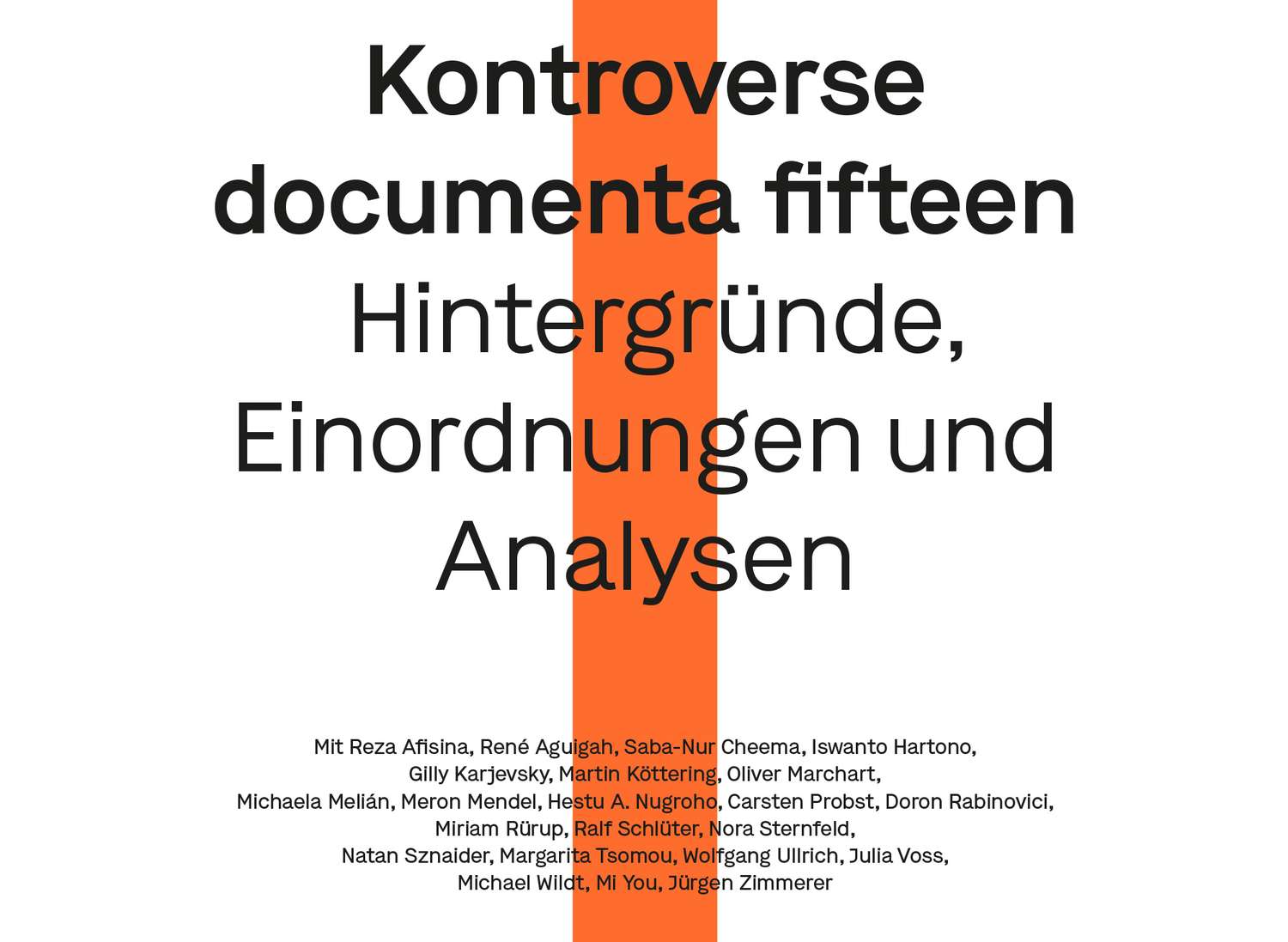

Symposium: Controversy over documenta fifteen

Symposium: Controversy over documenta fifteen

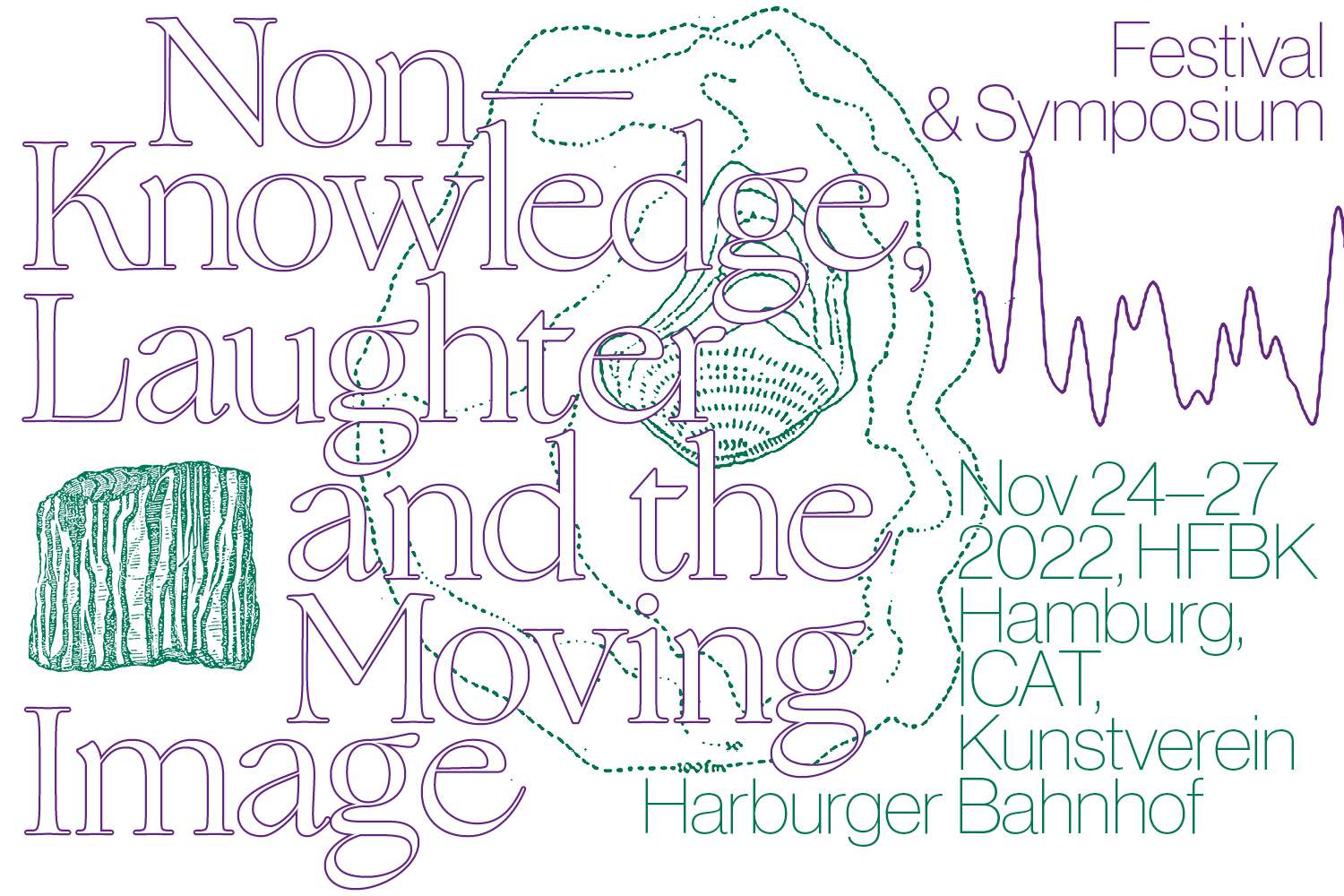

Festival and Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

Festival and Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

Solo exhibition by Konstantin Grcic

Solo exhibition by Konstantin Grcic

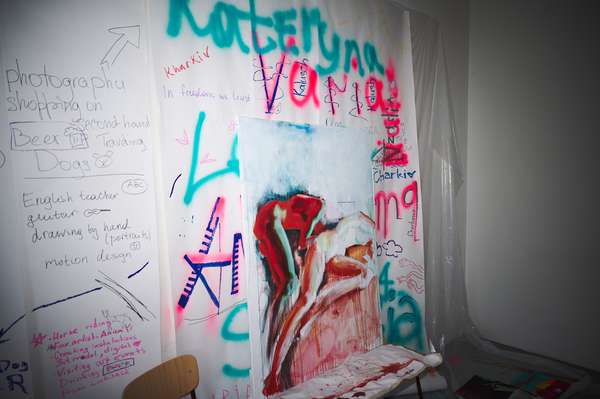

Art and war

Art and war

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

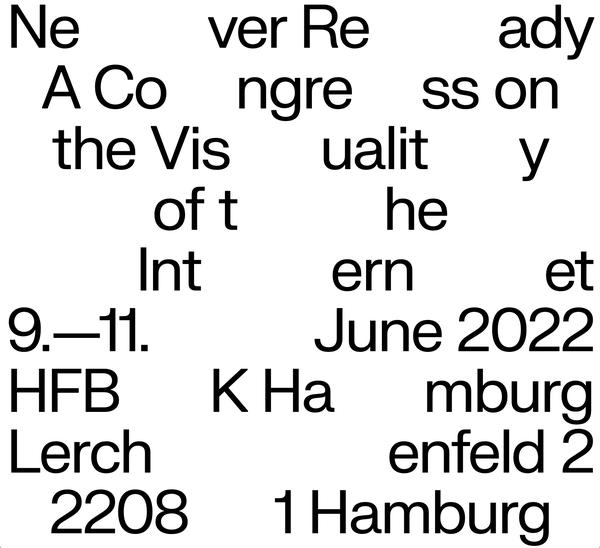

June is full of art and theory

June is full of art and theory

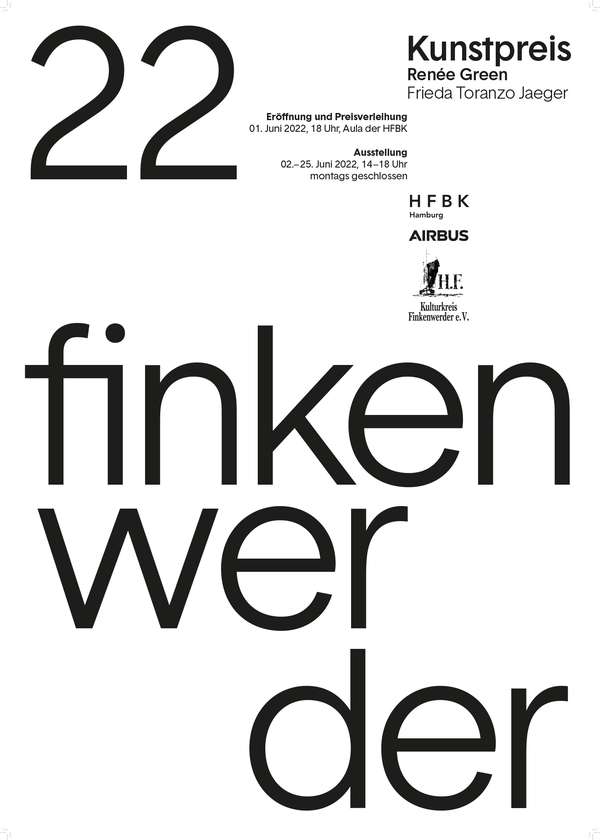

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2022

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2022

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Raum für die Kunst

Raum für die Kunst

Annual Exhibition 2022 at the HFBK

Annual Exhibition 2022 at the HFBK

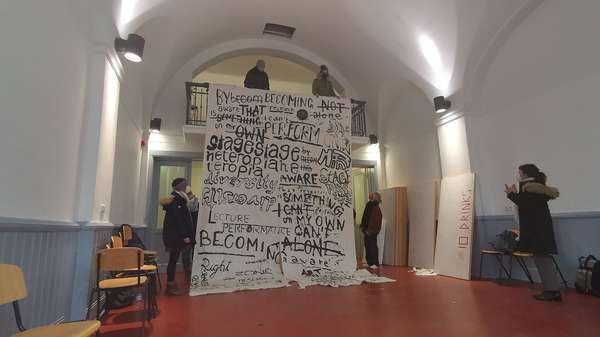

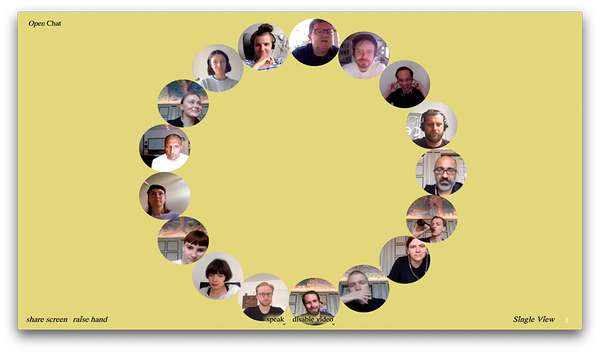

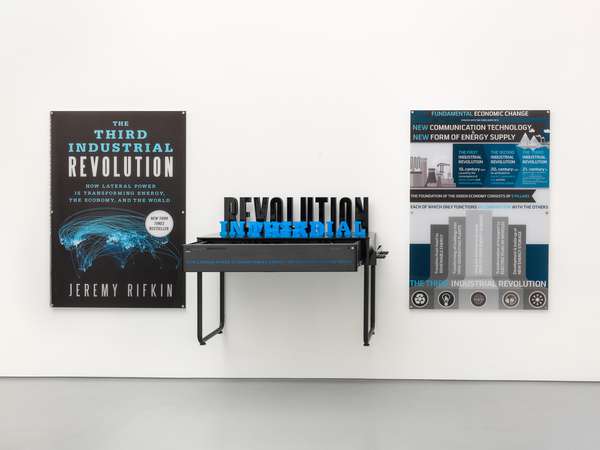

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments.

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments.

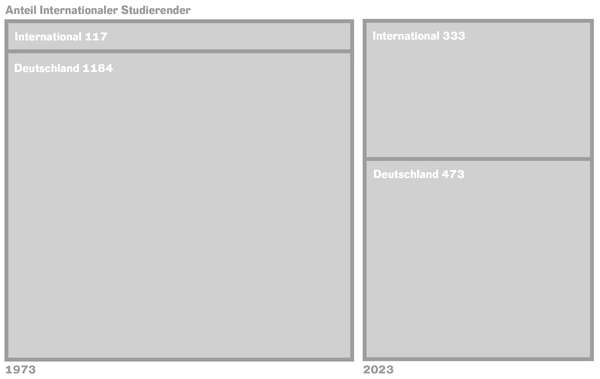

Diversity

Diversity

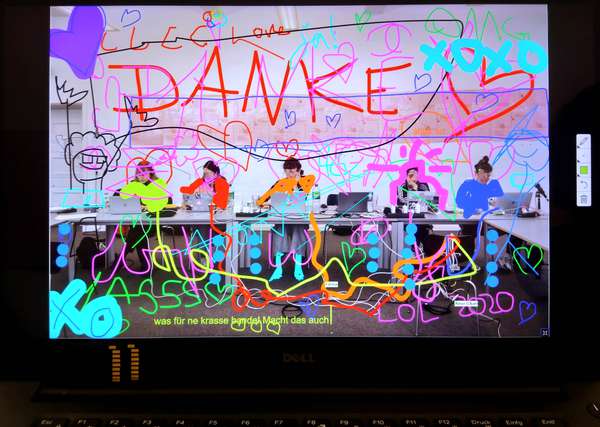

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

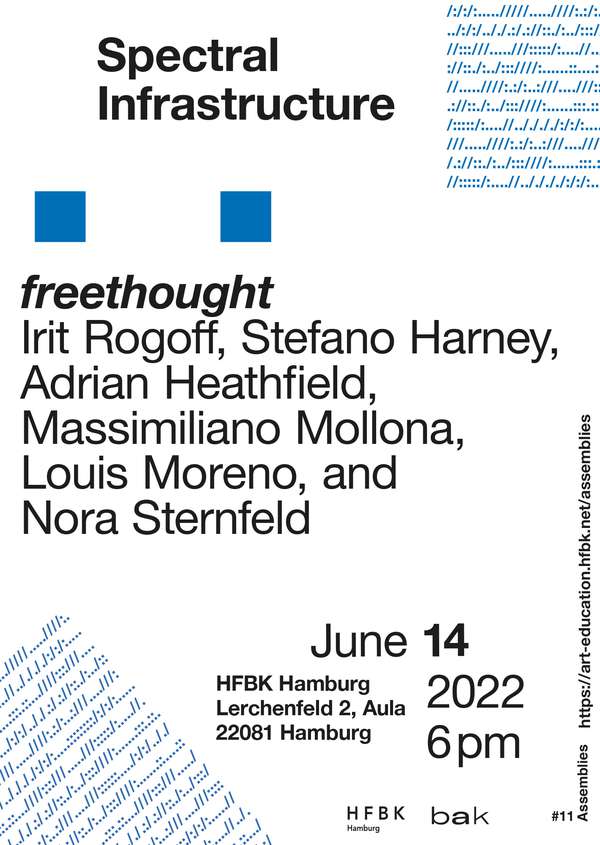

Unlearning: Wartenau Assemblies

Unlearning: Wartenau Assemblies

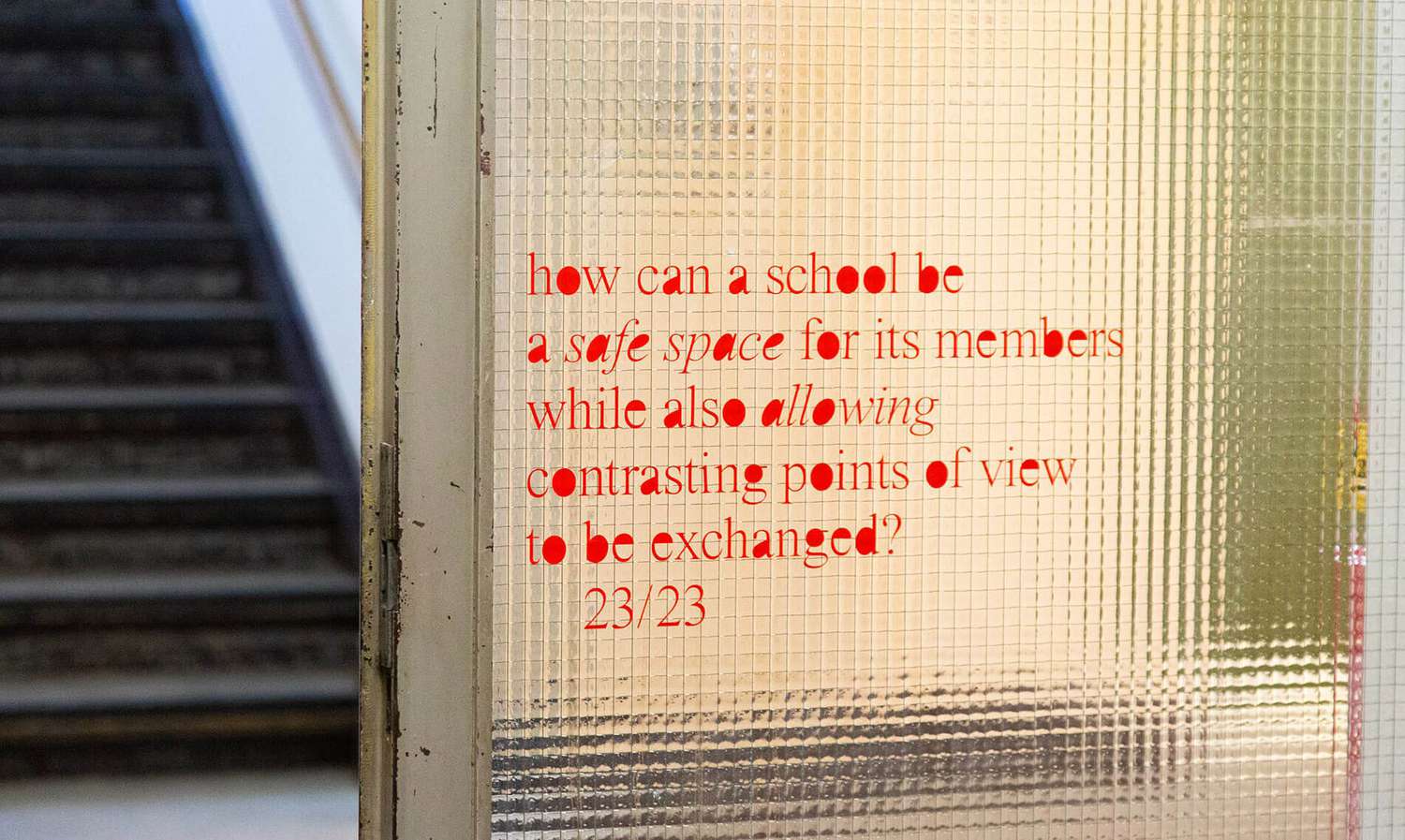

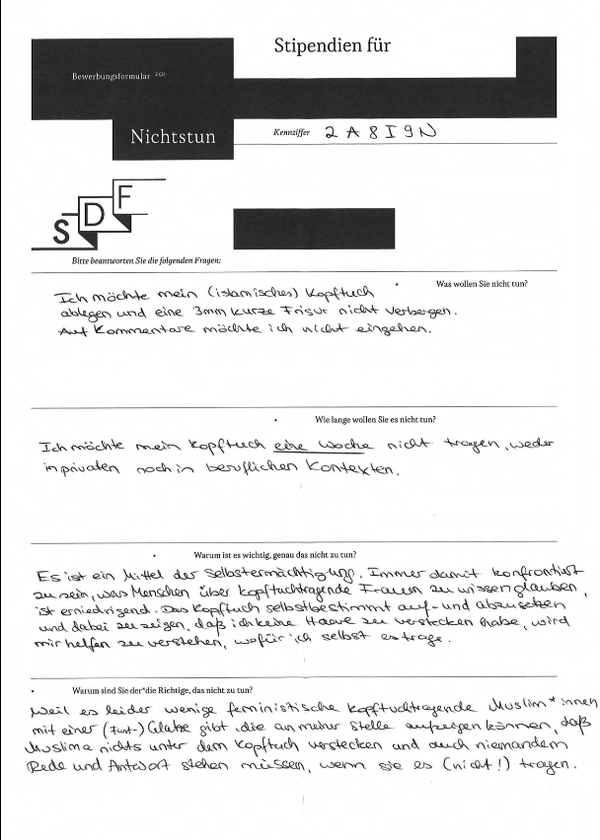

School of No Consequences

School of No Consequences

Annual Exhibition 2021 at the HFBK

Annual Exhibition 2021 at the HFBK

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

Teaching Art Online at the HFBK

Teaching Art Online at the HFBK

HFBK Graduate Survey

HFBK Graduate Survey

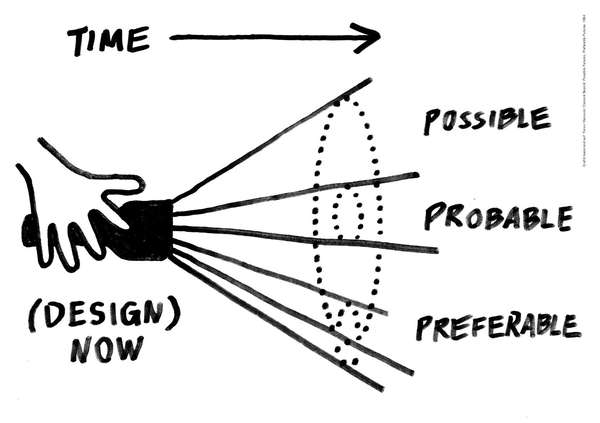

How political is Social Design?

How political is Social Design?