A Life Spent Drawing

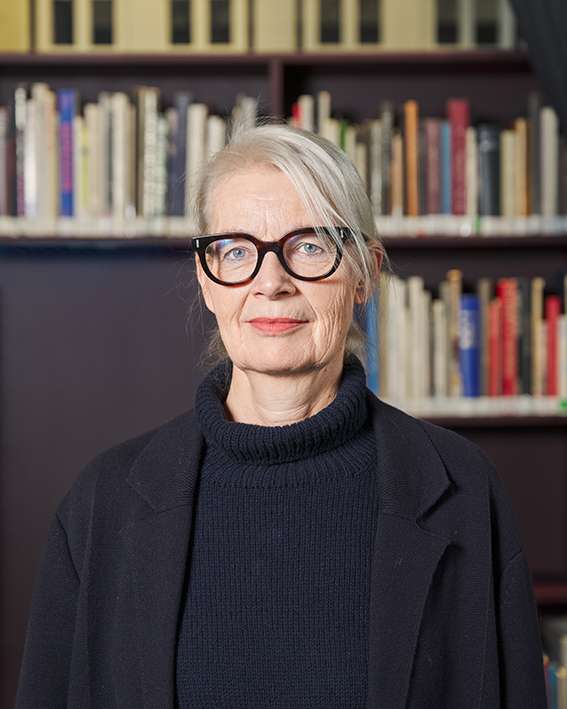

Seda Yıldız in conversation with the Turkish illustrator and former HFBK student Betül Dengili Atlı about her time in Hamburg and her artistic career.

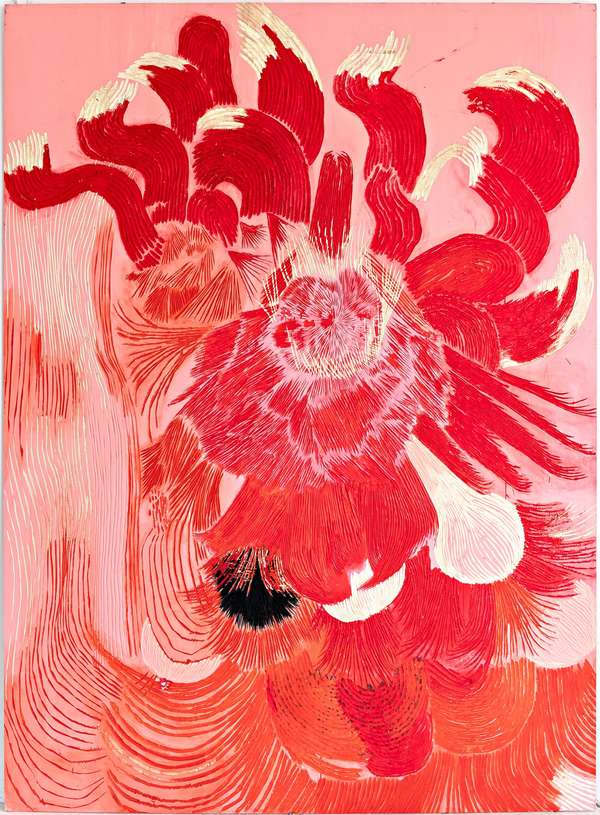

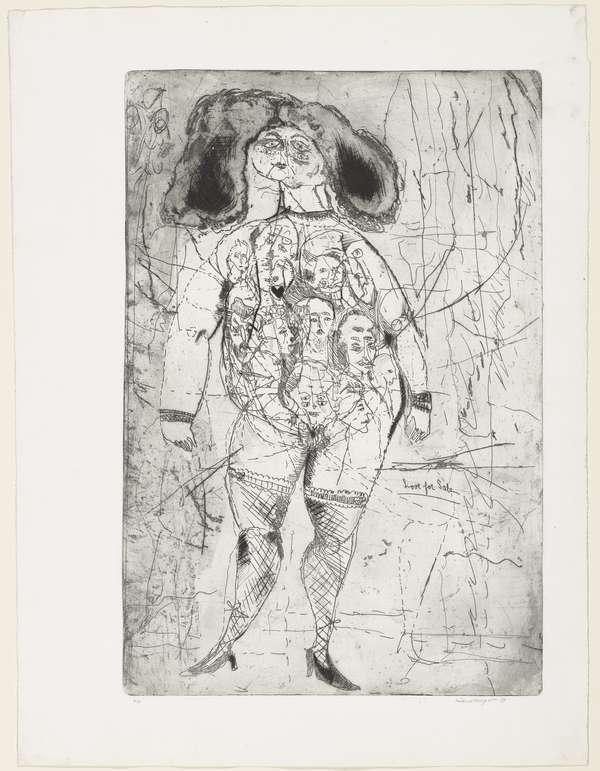

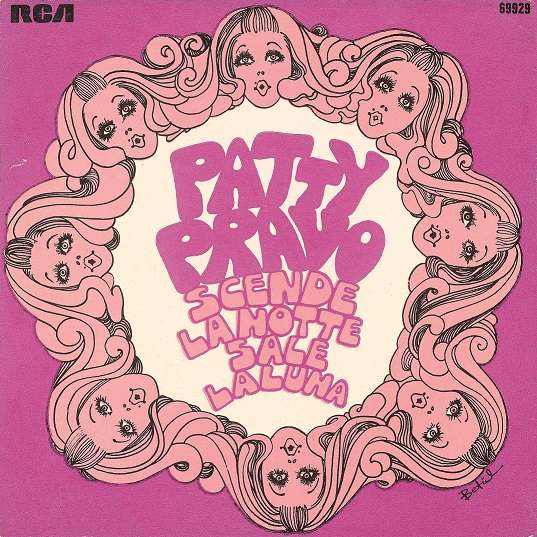

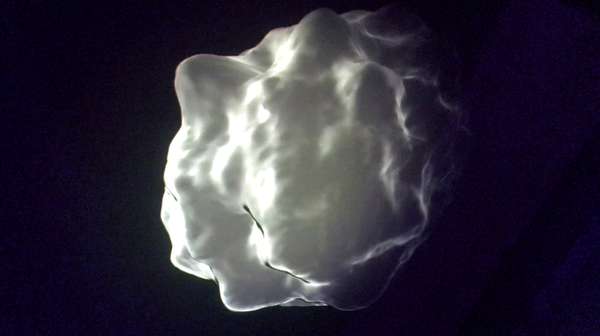

Professor Betül Dengili Atlı was among the highly skilled students the Turkish government supported with graduate education scholarships abroad as part of Turkey’s modernization policies. These policies, which date back to 1929, sought to train Turkish students abroad, who in return would contribute to the development of public institutions and the future of their home country.[1] Upon graduating from the Istanbul State Academy of Fine Arts (now the Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University) in 1968, Atlı received a scholarship offer through her professor Sabih Gözen, the founder of the fabric patterns workshop at the academy. Though she focused on textiles during her studies, Atlı ended up working as an illustrator, since the textile industry was still nascent in Turkey at the time. Working as an illustrator, Atlı created album covers for various foreign releases in Turkey. In just eight months she produced her most well-known works, including illustrations for Led Zeppelin, Iron Butterfly, Jethro Tull, Patty Pravo, Rainbow, and others. Her multilayered illustrations present a world within a world, a dreamy atmosphere composed of highly elaborated and interlaced patterns. Though she calls this the best adventure of her career, Atlı’s motivation to pursue an academic career let her to accept the offer, and she arrived in Germany in 1970 to earn her PhD.

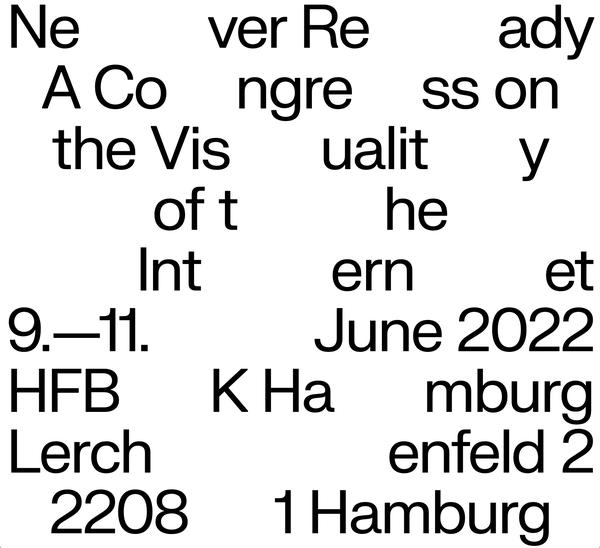

Her first stop was Munich, where she participated in a year-long German language program. However, it came as a surprise to her that Germany had no doctoral program in art at the time. After extensive correspondence with the Turkish authorities, the plan became clear: Atlı would receive a degree from a German academy and return to Turkey for her eight years of obligatory service. The fashion department of the Kassel Art Academy was her first choice. Atlı describes her first impressions upon arriving in Kassel: “I couldn’t believe how in 25 years Germany had recovered from the effects of the war. The city was rebuilt, and there were no traces of destruction. The studios at the academy were full of materials and equipment. Whatever one could imagine was available, but there were no teachers, no students. It was almost a ghost space.” Disappointed, Atlı asked to be transferred to the HFBK Hamburg in 1972, to the class of “Frau Hildebrand,” who was recommended to her. Frau Hildebrand turned out to be the renowned German textile designer Margret Hildebrand, who was also the first female professor appointed by the HFBK to the textile design department in 1956.[2]

During her time at the HFBK Hamburg, from 1972 to 1974, Atlı and Hildebrand did not have many interactions. “I arrived at the HFBK and saw Frau Hildebrand working in a studio behind glass windows. She would spend her days there doing her personal things. There was no regular exchange between students and teachers,” she recalls. As in Kassel, Atlı found it odd that there were no classes, group discussions, or meetings, but only empty classrooms and studios. “Only occasionally did someone from a ceramic factory bring broken pots and plates, and then we could work on making patterns. That was pretty much how our education was,” she explains. “That extreme freedom made it seem like the students were being ignored.”

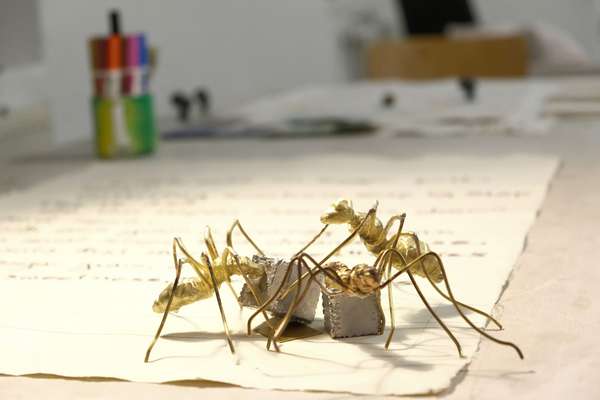

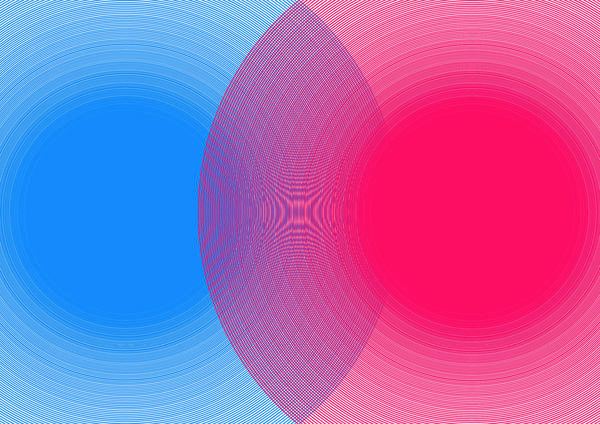

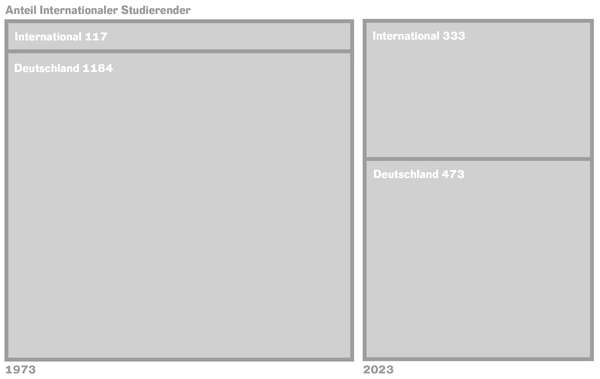

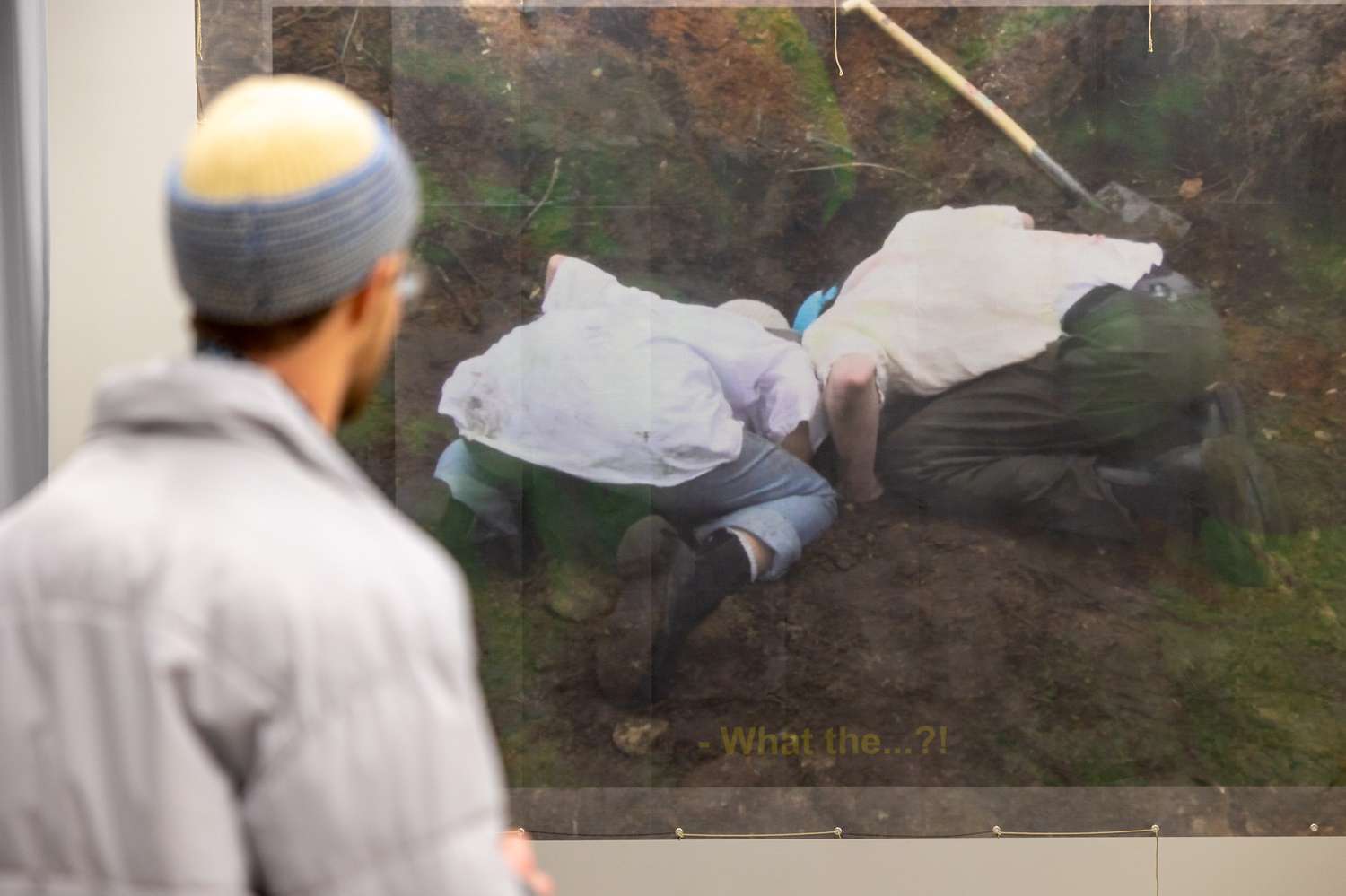

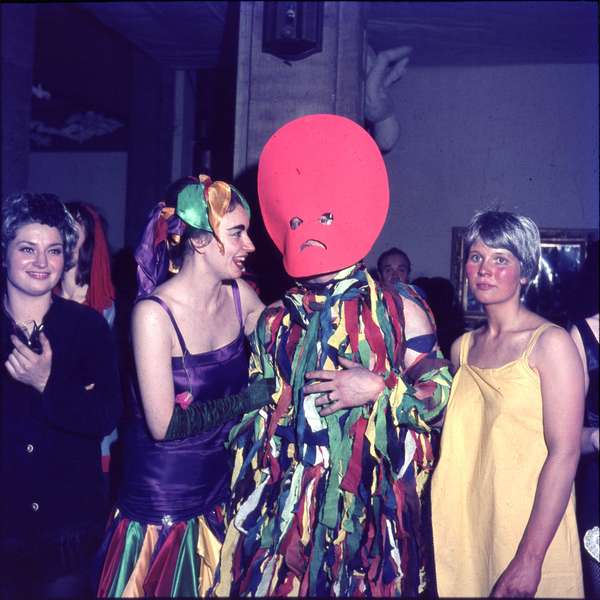

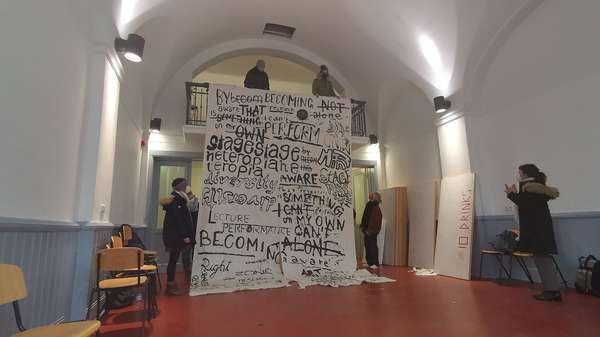

During her time at the HFBK Hamburg, Atlı mainly worked on creating graphic patterns. It was one of these pieces that she also displayed in the exhibition of international students held at the HFBK Hamburg in 1973. The exhibition, which had no proper opening, did not attract much interest from the public, as she recalls: “It was right after the hippie movement. People were not interested in events such as exhibition openings or competitions. There was this reckless approach like, ‘What is competition?’ ‘What is success?’ ‘Who decides?’” Nonetheless, it was a unique experience and Atlı’s first encounter with conceptual art, including installations made from found objects. Along with her printed work, there was one children’s book illustration from a graphic design student on display. Such works on paper did not draw much attention at the time, she notes.

For Atlı, it was not the education she received in Germany, but the social and cultural life that contributed significantly to her personal development. The encounters during her stay at the international student dormitory influenced her personality and her approach to teaching, and also helped her build tolerance for differences. It was the first time she had the opportunity to meet people of different nationalities, saw a shopping mall, tasted foreign cuisines, and visited museum exhibitions. “These experiences were a school to me. They helped me develop a broader perspective in my life.” In 1972, while Atlı was still in a language course in Munich, she won the international competition organized by Für Sie, one of Germany’s leading women’s magazines. Her work, which was chosen among some 5000 entries, was an embroidery created on her own drawing. “Perhaps nobody ever heard about it at the HFBK Hamburg. Nobody showed curiosity in my work, neither in this prize, nor the record covers I designed in Turkey,” Atlı explains. Some of the record covers she designed for albums by Led Zeppelin, Elvis Presley, Patty Pravo, as well as Turkish psychedelic artists such as Cem Karaca and Barış Manço are in private collections and are sold at auction for high prices today.

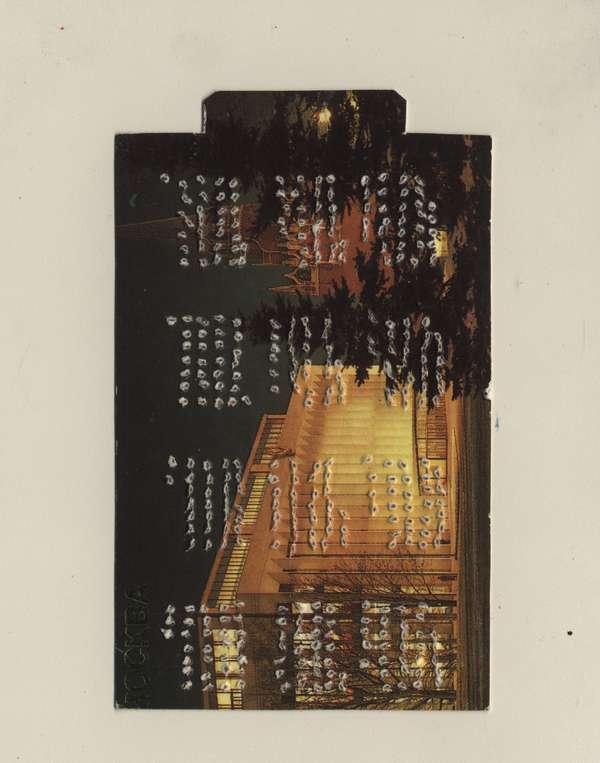

Atlı graduated from the HFBK Hamburg in 1973. Her final project was a wallpaper design as well a thesis in German on Turkish miniatures. Staying in Germany did not even occur to her. “Will I work in a textile factory or become an assistant at the academy by the sea in Istanbul?” she wondered after graduating. She chose the latter. Ironically, the diploma she received was not recognized by any public institution in Turkey. What remains valid from her time is the wallpaper she designed for her final project, which later became the cover for the album Denizaltı Rüzgarları (1975) by the acclaimed Turkish jazz percussionist Okay Temiz. Atlı began working as a teaching assistant in the textile department at the Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University in 1975, where she continued working for 35 years, until she retired with the title of professor in 2008. With the growth of the textile industry in the early 1990s in Turkey, she helped create the textile department in 1994, which was expanded in 2004 to also include fashion design. During this time, she also introduced theoretical courses such as the history of twentieth-century costume and fashion design. Atlı continues to teach courses on drawing and fashion at private universities in Turkey.

Though her career took a turn toward textile and fashion design, Atlı has always been fond of creating illustrations for albums and children’s books. Following the vinyl revival that started in the early 2000s, after a 40-year break Atlı designed the cover for the Istanbul-based psychedelic rock band Nemrud in 2016, which sparked interest in her work as an illustrator.

This was followed by the limited-edition vinyl covers she created for Erkin Koray (Tamam Artık, 2017), Barış Manço (Darısı Başınıza, 2020), Cem Karaca (Yiğitler, 2021), and Edip Akbayram (Özgürlük, 2021). In 2021 she exhibited her illustrations at the Vinyl Festival in Istanbul. As she contemplates the eventual end of her career, Atlı appreciates how particularly young people, to her surprise, attach such value to these covers inherited from their families. Perhaps some of these illustrations will inspire others to start drawing themselves.

Seda Yıldız (*1989, Istanbul) is an independent curator and writer based in Hamburg. Her practice is inspired by thinking across disciplines including art, music, design, literature, and activism. She is particularly interested in taking part in process-oriented, open, and experimental projects that foster collaboration and exchange with a wider audience. More information is available at yildizseda.com.

Notes

This article appeared in Lerchenfeld issue #67.

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

Long days, lots to do

Long days, lots to do

Cine*Ami*es

Cine*Ami*es

Redesign Democracy – competition for the ballot box of the democratic future

Redesign Democracy – competition for the ballot box of the democratic future

Art in public space

Art in public space

How to apply: study at HFBK Hamburg

How to apply: study at HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2025 at the HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2025 at the HFBK Hamburg

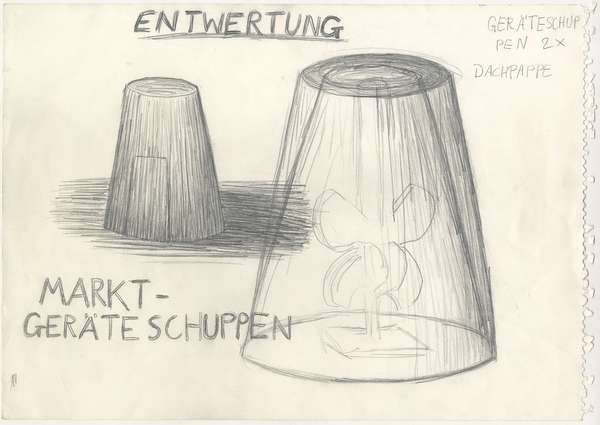

The Elephant in The Room – Sculpture today

The Elephant in The Room – Sculpture today

Hiscox Art Prize 2024

Hiscox Art Prize 2024

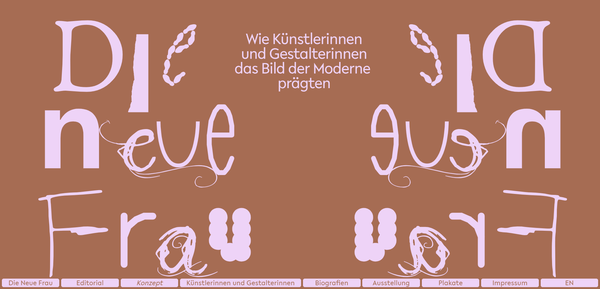

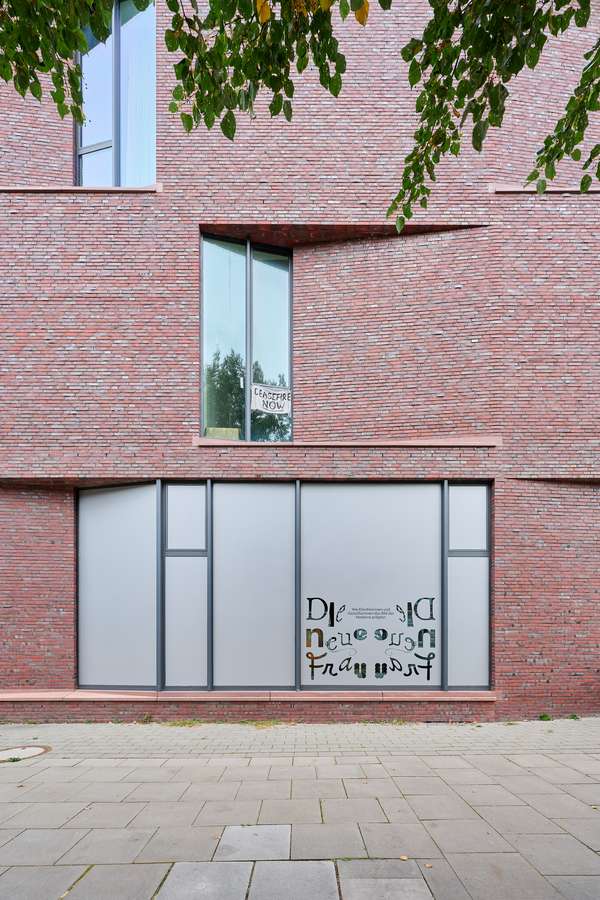

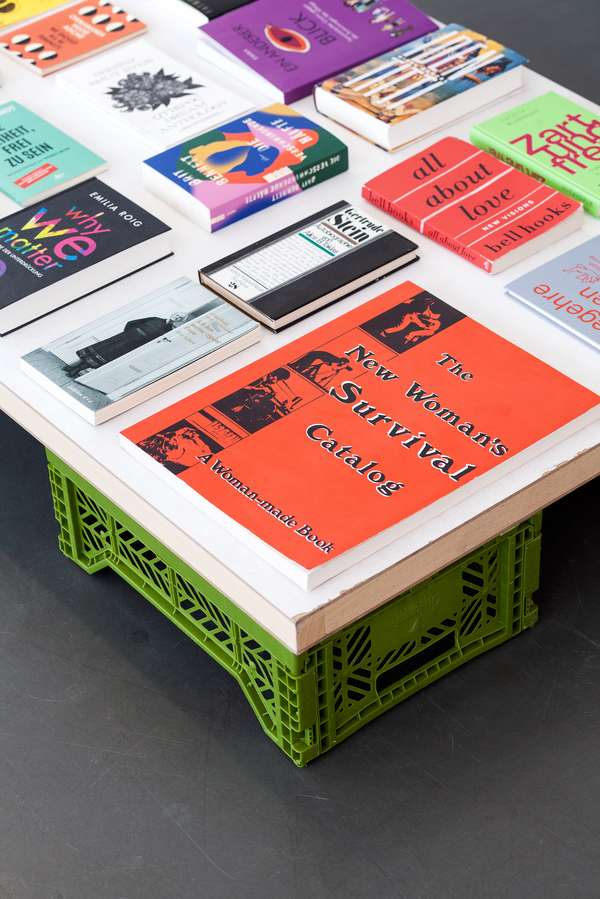

The New Woman

The New Woman

Doing a PhD at the HFBK Hamburg

Doing a PhD at the HFBK Hamburg

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2024

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2024

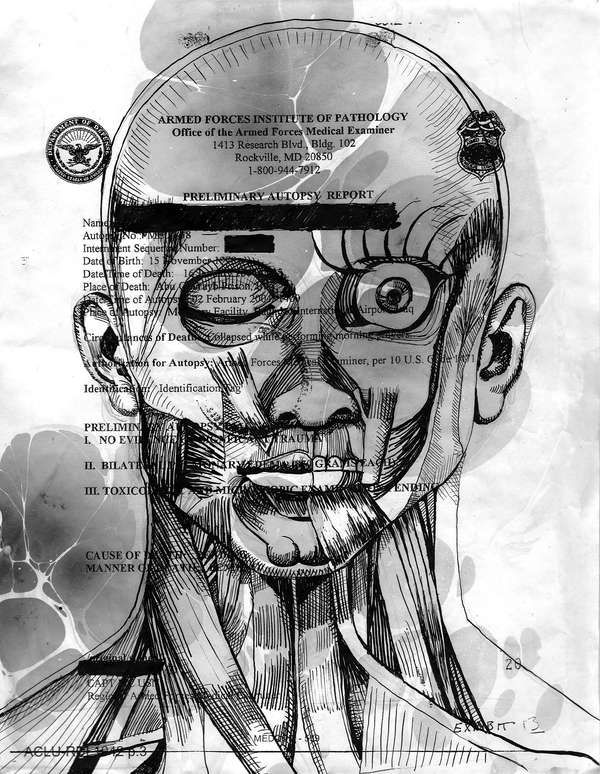

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

New partnership with the School of Arts at the University of Haifa

New partnership with the School of Arts at the University of Haifa

Annual Exhibition 2024 at the HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2024 at the HFBK Hamburg

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

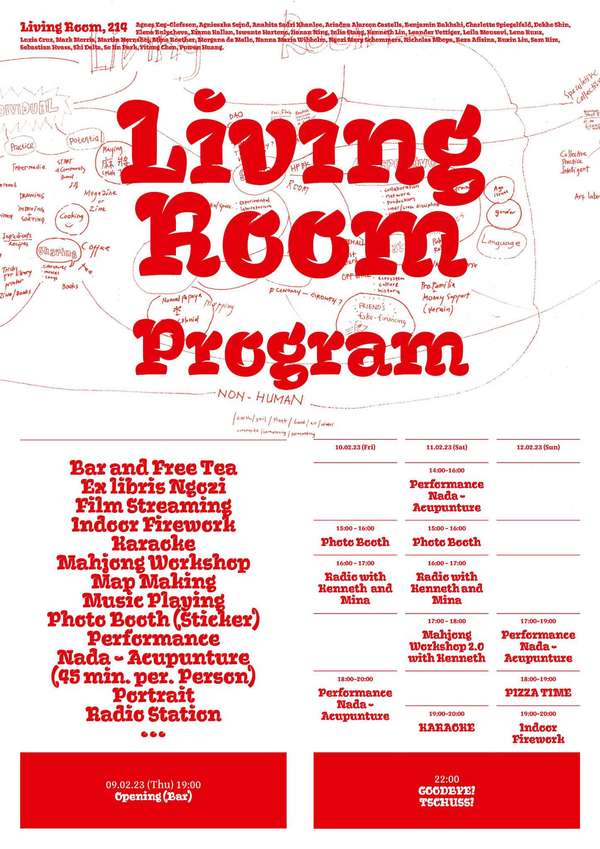

Extended Libraries

Extended Libraries

And Still I Rise

And Still I Rise

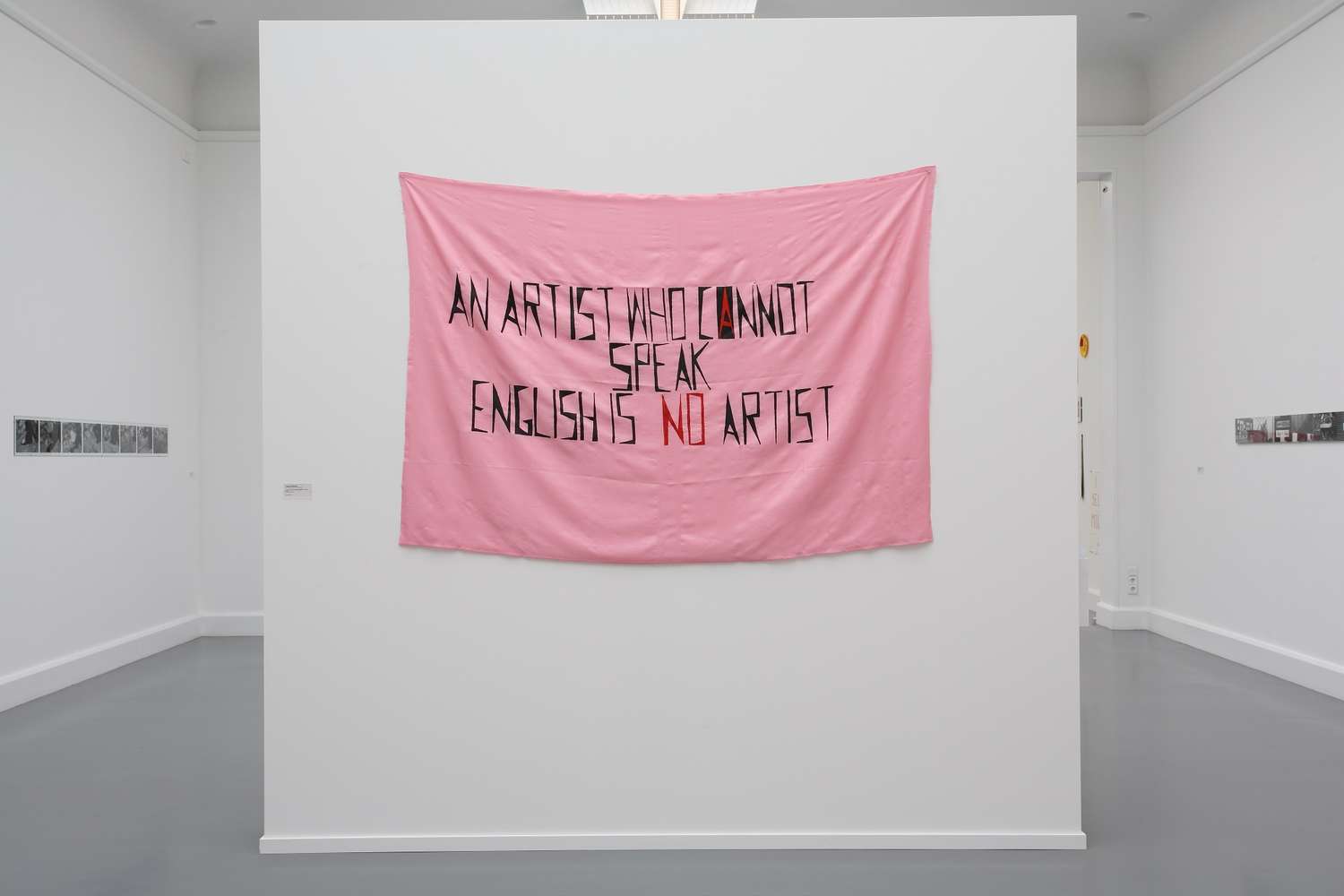

Let's talk about language

Let's talk about language

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

Let`s work together

Let`s work together

Annual Exhibition 2023 at HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2023 at HFBK Hamburg

Symposium: Controversy over documenta fifteen

Symposium: Controversy over documenta fifteen

Festival and Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

Festival and Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

Solo exhibition by Konstantin Grcic

Solo exhibition by Konstantin Grcic

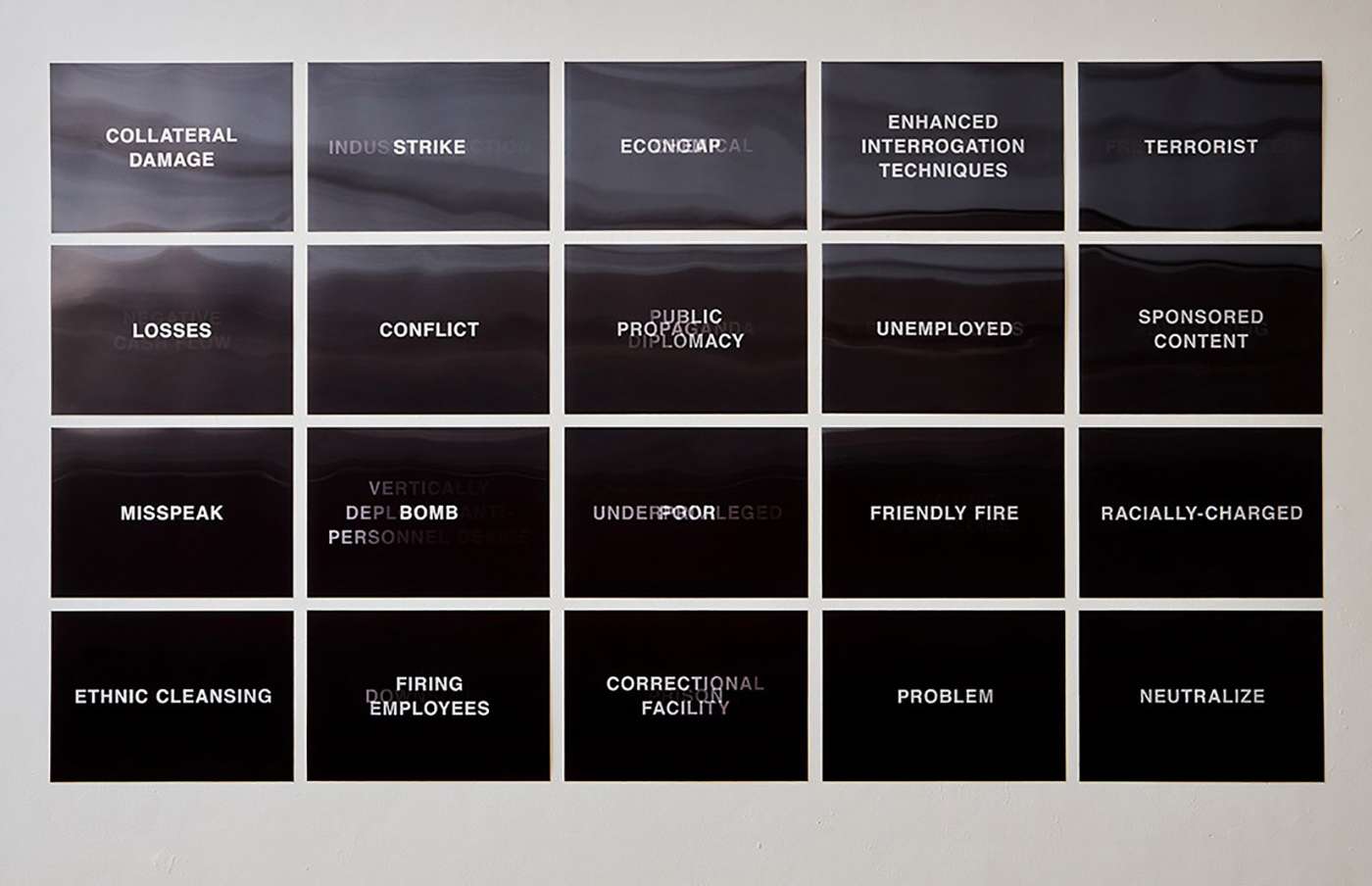

Art and war

Art and war

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

June is full of art and theory

June is full of art and theory

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2022

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2022

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Raum für die Kunst

Raum für die Kunst

Annual Exhibition 2022 at the HFBK

Annual Exhibition 2022 at the HFBK

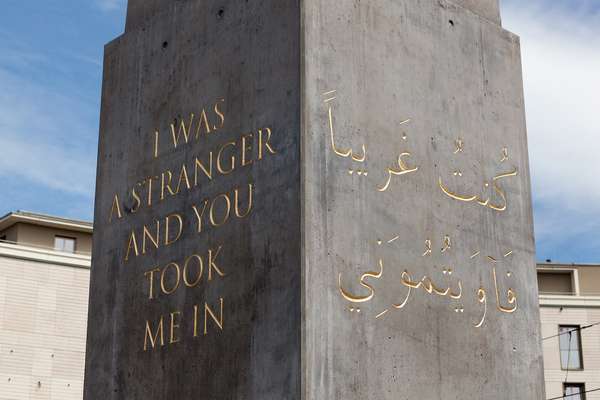

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments.

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments.

Diversity

Diversity

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

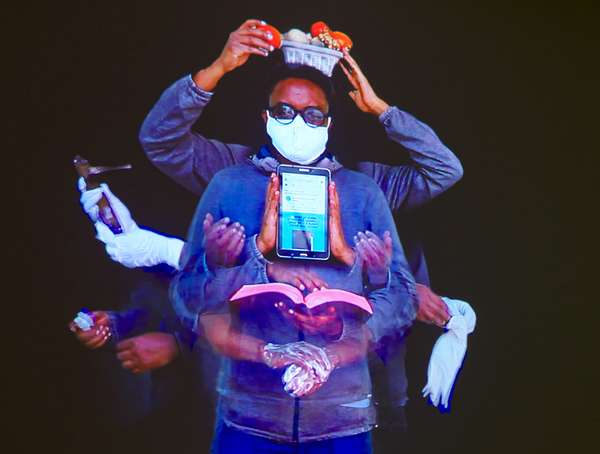

Unlearning: Wartenau Assemblies

Unlearning: Wartenau Assemblies

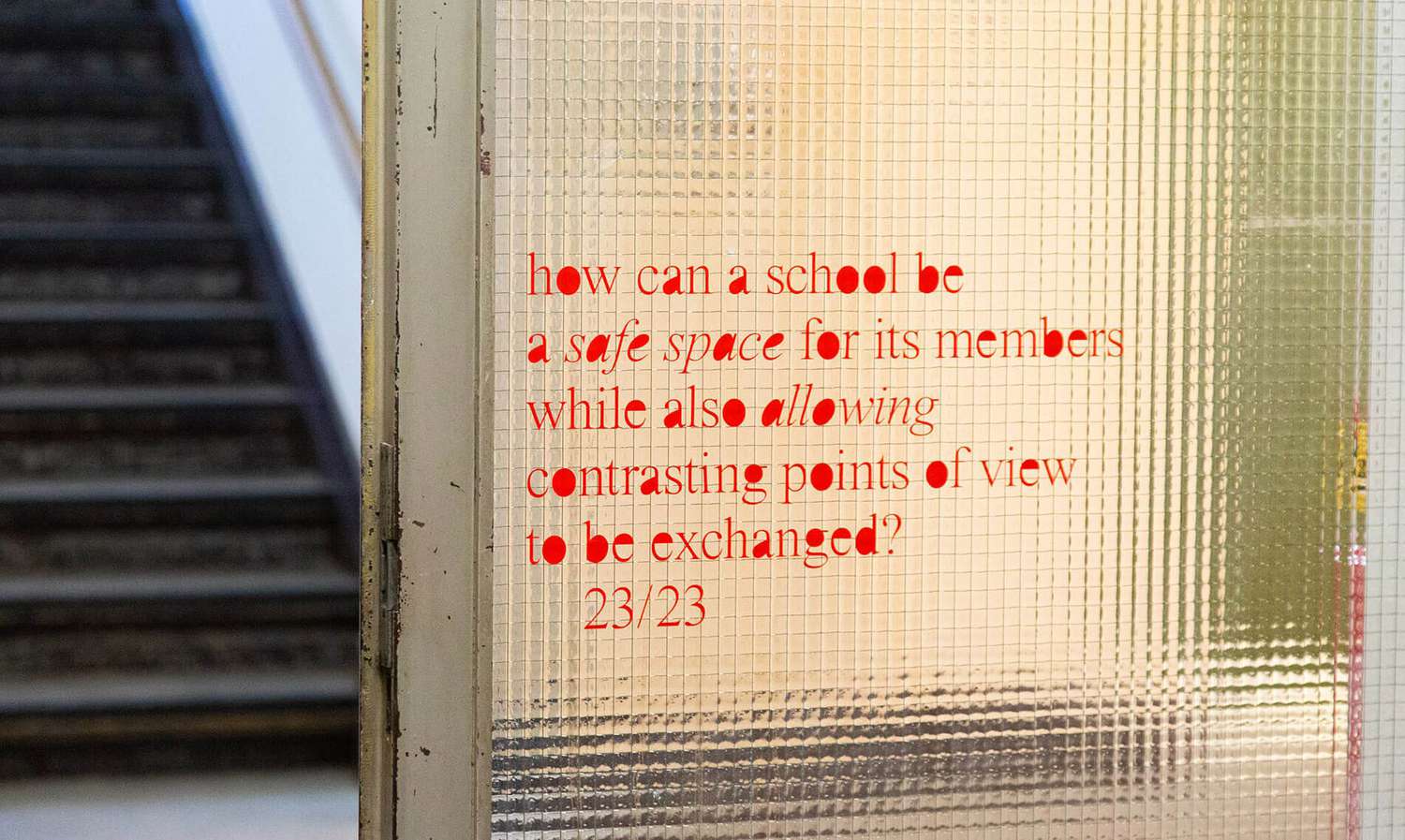

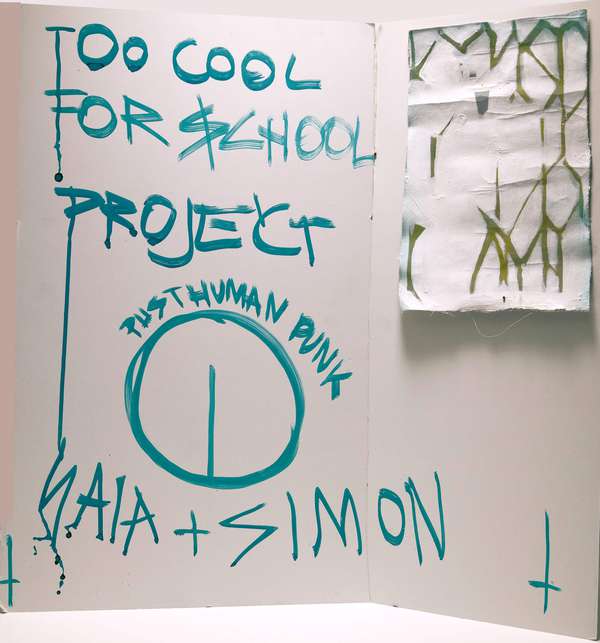

School of No Consequences

School of No Consequences

Annual Exhibition 2021 at the HFBK

Annual Exhibition 2021 at the HFBK

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

Teaching Art Online at the HFBK

Teaching Art Online at the HFBK

HFBK Graduate Survey

HFBK Graduate Survey

How political is Social Design?

How political is Social Design?