What do you actually do? – Monika Grzymala

“I always describe myself as a sculptor who makes drawings,” says Monika Grzymala. Glancing around her one-room studio, the artist’s gaze comes to rest on a wall-based installation made from lengths of black and silver adhesive tape. Created for an exhibition at Lisson Gallery in 2016, what’s visible is only a small section of a much larger work. The real thing, Grzymala tells me, took three days to make and spread like a spider web across an entire room of the London-based gallery. It’s a process she calls “Raumzeichnung” or spatial drawing. “I see all my installations in this way,” she says, “but there are still some people who ask, ‘What’s this got to do with drawing?’”

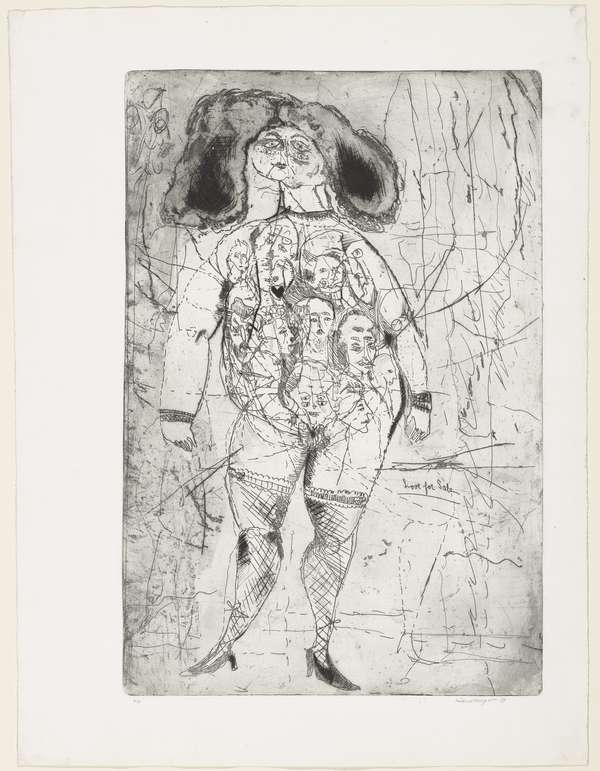

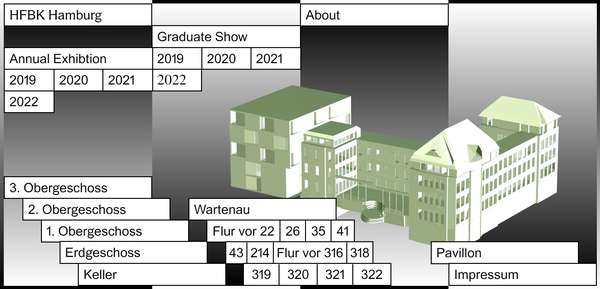

A lot, as it happens. Grzymala brings down a box of loose sketches from a set of metal shelves and flicks through them. Black ink on textured handmade paper, each page shows a combination of swirling, interconnecting lines. “I [use drawing to] try out different lines and shapes,” she explains. “It’s always a line but in various emotional states.” Trained in classical stone sculpture, Grzymala first began making these abstract drawings when she moved to Hamburg to study at the HFBK in the mid-1990s. Finding herself alone in an unheated apartment—“the milk froze on my kitchen table”—Grzymala picked up a pen and started drawing a line in an empty sketchbook. “This line continued from one page to another,” she recounts. “At some point it left the sketchbook and carried onto the table and the surrounding walls.”

For over twenty years now, the Berlin-based artist has been expanding on this initial discovery in ever more imaginative ways. Interested in the moment in which drawing becomes sculpture, she’s painted on ice to create an artwork that skaters could glide across in Hamburg, covered the walls of Vienna’s Albertina Museum with 3,6 km masking tape, and collaborated with Aboriginal artists on a flowing installation of paper and string for the 18th Biennale of Sydney. But despite working like this for decades, for Grzymala it’s still a challenge to move from two dimensions into three. “The step into space is always a painful decision,” she says.

At the time of our studio visit, Grzymala is working on a commission for the courtyard of the Graphic Collection Kupferstich-Kabinett in Dresden, as part of the celebrations for the museum’s 300th anniversary. Pointing to an architectural model of the proposed work, she tells me that the installation’s forms are inspired by portrayals of paper scrolls from the museum’s collection. “You see them in every print and drawing,” she explains. “They usually contain a written message, but there are many prints by Albrecht Dürer, for example, where they’re left empty, and are—in my eyes—describing space.” For the museum, Grzymala is planning to replicate these scrolls using a lightweight paper material to create forms that will hover over the heads of the museum’s visitors, encouraging them to experience this historic space differently in the process.

This isn’t the only time that the sculptor has worked in a public space. In 2018 she was asked to create a permanent site-specific installation for the atrium of the Hubben Uppsala Science Park in Sweden. The resulting sculpture, which comprised two twisting, meandering lines based on the unique “double helix” shape of DNA, took her a year to complete. “Constructing it was a real challenge,” Grzymala says of the 2.8 ton, 25-meter-high sculpture. Unlike her paper or adhesive tape installations, which Grzymala usually builds without assistance, in Sweden, she had to work with structural engineers, metal workers, sculptors and painters. It wasn’t always an easy process. “All the engineers you consult start saying, ‘no it’s not going to work, it’s much too thin,’” she says. “I was always more confident than them. I said, ‘believe me it’s going to work’ and it did!”

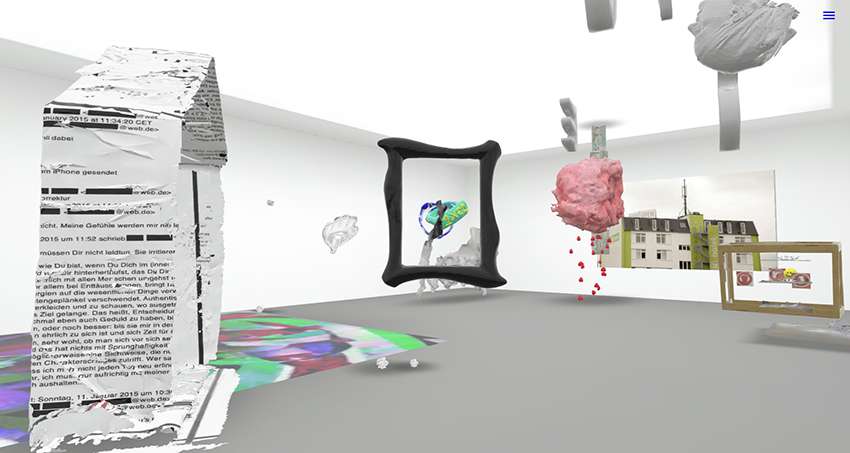

In an effort to combat the labour-intensive nature of works like these, Grzymala has been experimenting with virtual reality. “The hope is to create works that I don’t need to travel with in the difficult way I’m doing at the moment,” she says. “It’s a lot: you have to do a site visit then you have to come back when you’re installing the piece. Sometimes you’re in places that are extremely hot or cold. You also have to fly there and deal with the time differences.” Beyond the practical reasons for working with VR, it also has the ability to take Grzymala’s bombastic work to the next level. “VR allows me to do things that are far beyond physical limits,” she enthuses. “I can walk on the ceiling or the walls if I want to. That’s what I’m attracted to. In this reality I have to deal with gravity.”

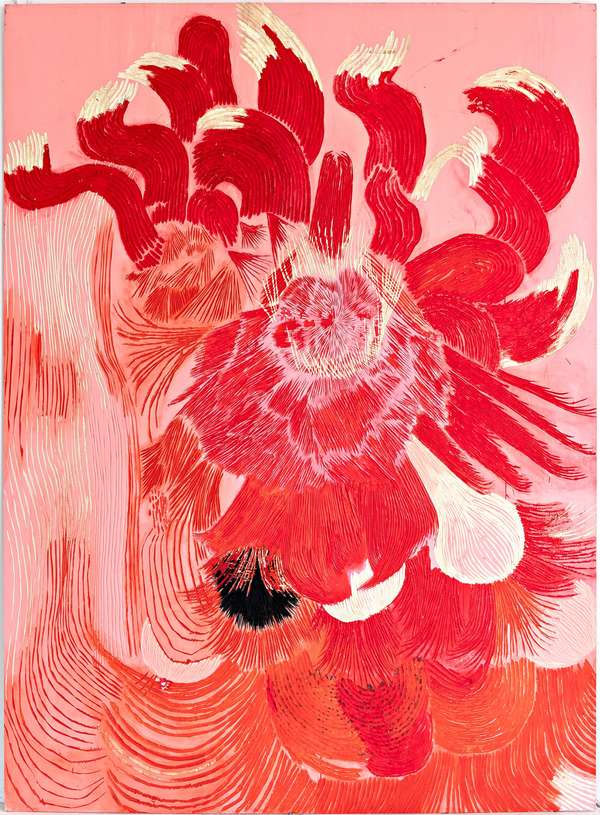

Ultimately though, Grzymala always comes back to her first love. After a bout of “cyber sickness”—too much time spent in virtual reality—left her feeling constantly nauseous, she recovered by returning to her studio and picking up a brush. “Drawing on hand made paper, which is so personal because it’s made from the used clothes of real people, and being able to observe how the ink soaked in, well that was great. It was a way to ground myself again.”

Monika Grzymala is a Polish-born German artist based in Berlin. She studied in Karlsruhe, Kassel and Hamburg. Her work has been exhibited internationally, including MoMA Museum of Modern Art, New York; Tokyo Art Museum; and Hamburger Kunsthalle.

HFBK graduate Chloe Stead, together with the photographer and also HFBK graduate Jens Franke, met former HFBK students to talk about work, life and art. It is the prelude to a series of interviews for the website of HFBK Hamburg.

Autumn program for everyone

Autumn program for everyone

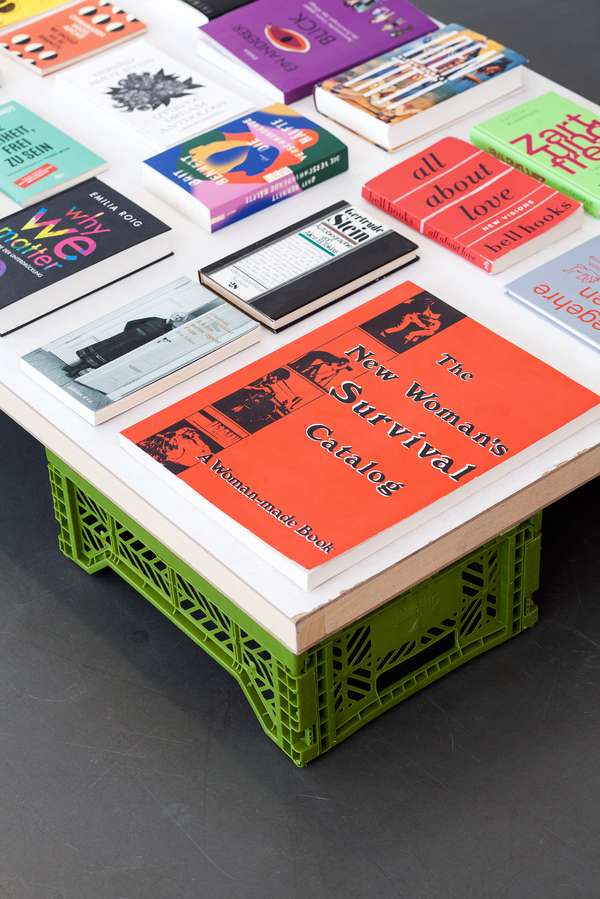

The New Woman

The New Woman

Opening of the 2024/25 semester centred on the new film house

Opening of the 2024/25 semester centred on the new film house

Doing a PhD at the HFBK Hamburg

Doing a PhD at the HFBK Hamburg

Summer of theory

Summer of theory

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2024

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2024

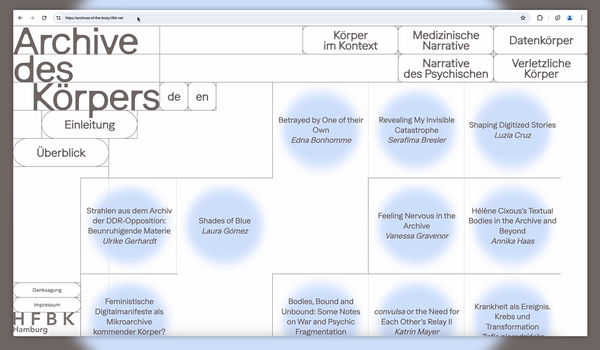

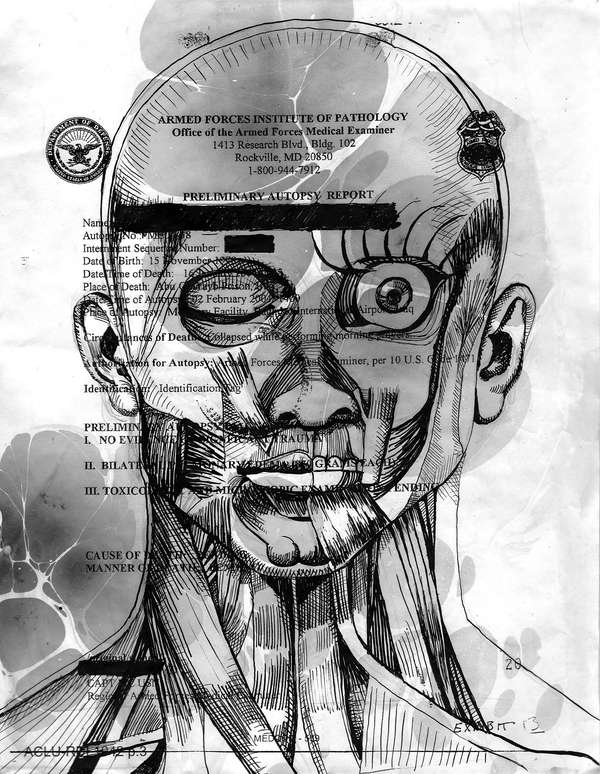

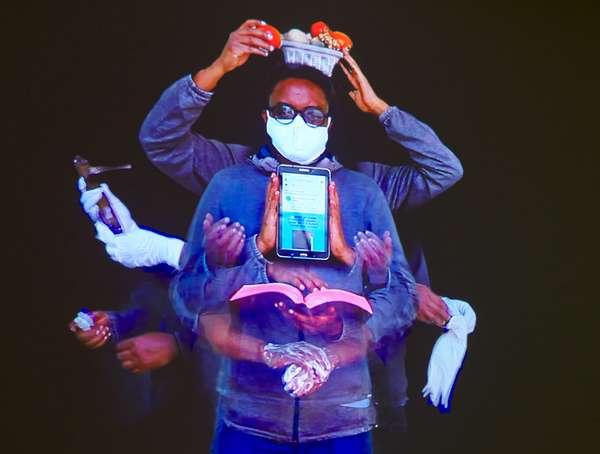

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

New partnership with the School of Arts at the University of Haifa

New partnership with the School of Arts at the University of Haifa

Exhibition recommendations

Exhibition recommendations

Annual Exhibition 2024 at the HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2024 at the HFBK Hamburg

How to apply: study at HFBK Hamburg

How to apply: study at HFBK Hamburg

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

Extended Libraries

Extended Libraries

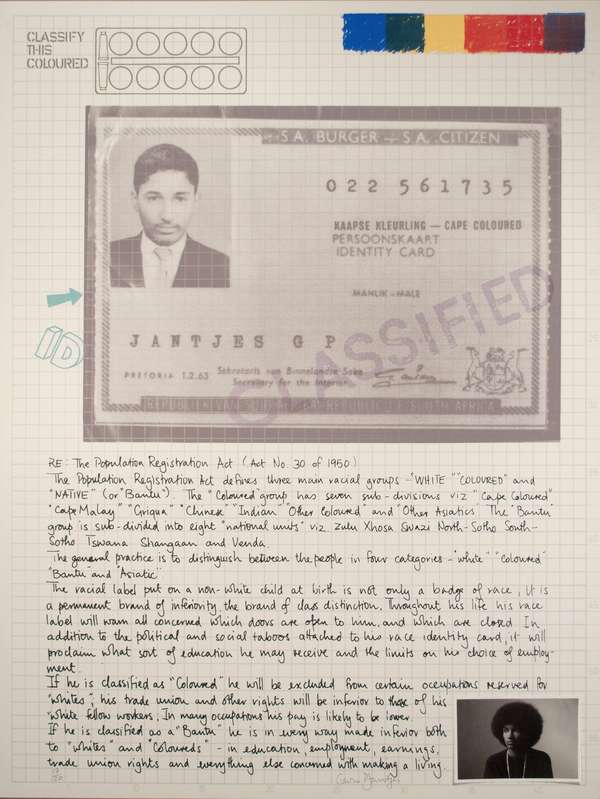

And Still I Rise

And Still I Rise

No Tracking. No Paywall.

No Tracking. No Paywall.

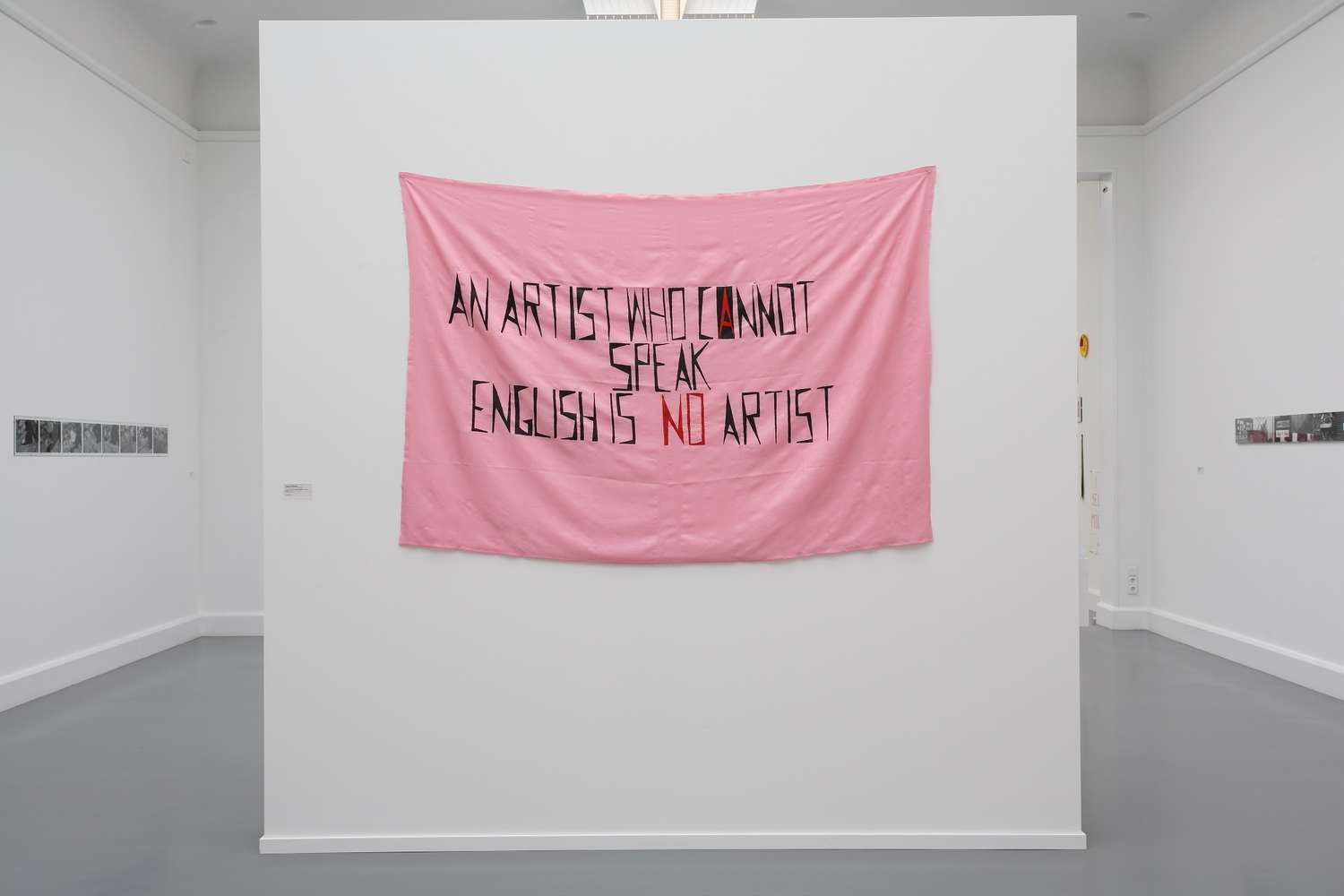

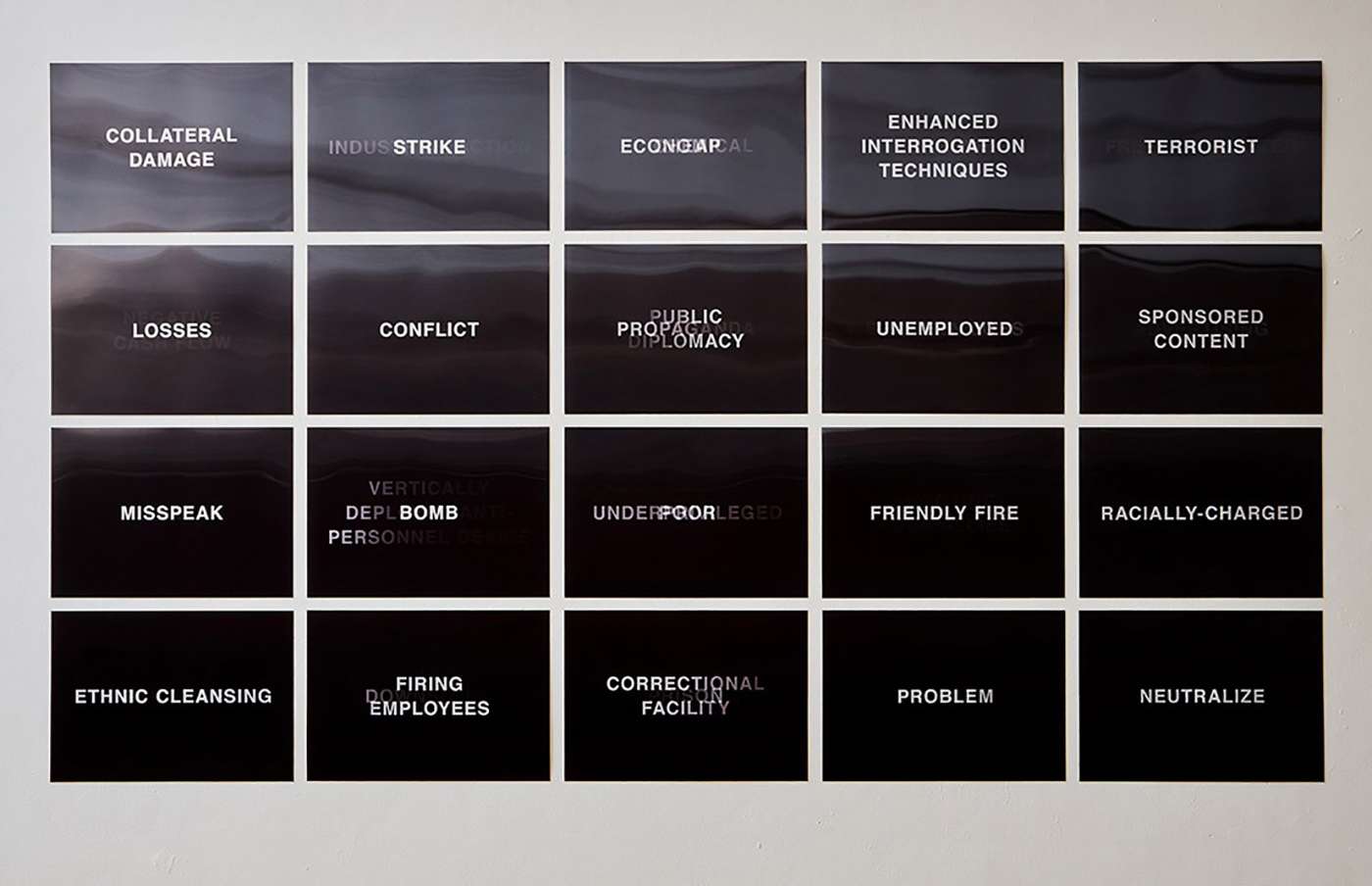

Let's talk about language

Let's talk about language

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

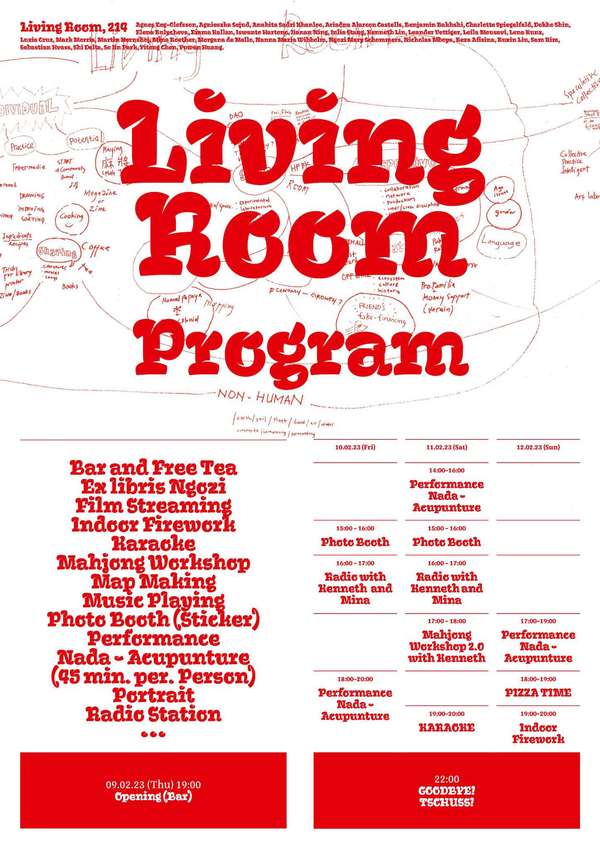

Let`s work together

Let`s work together

Annual Exhibition 2023 at HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2023 at HFBK Hamburg

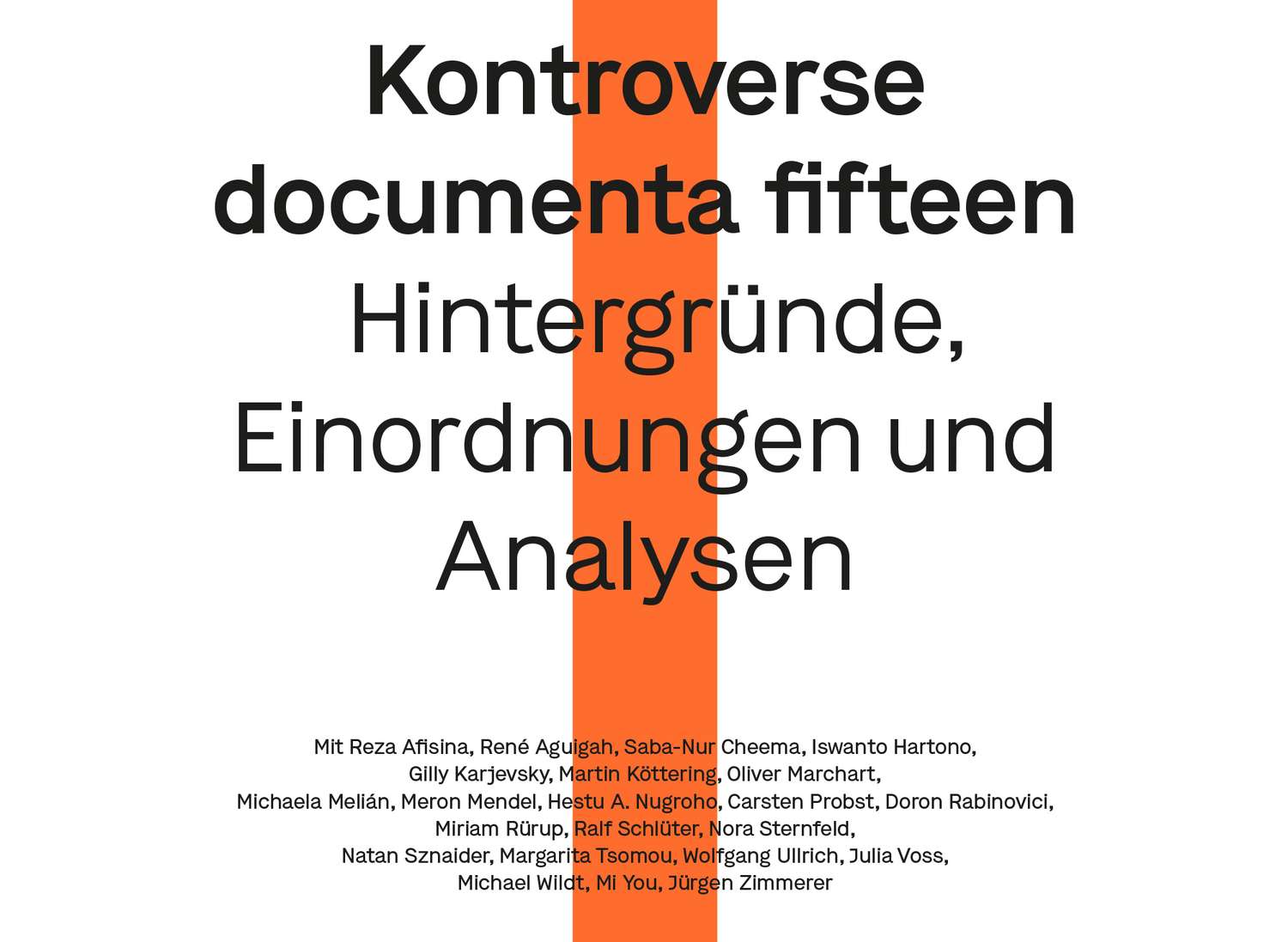

Symposium: Controversy over documenta fifteen

Symposium: Controversy over documenta fifteen

The best is saved until last

The best is saved until last

Festival and Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

Festival and Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

Solo exhibition by Konstantin Grcic

Solo exhibition by Konstantin Grcic

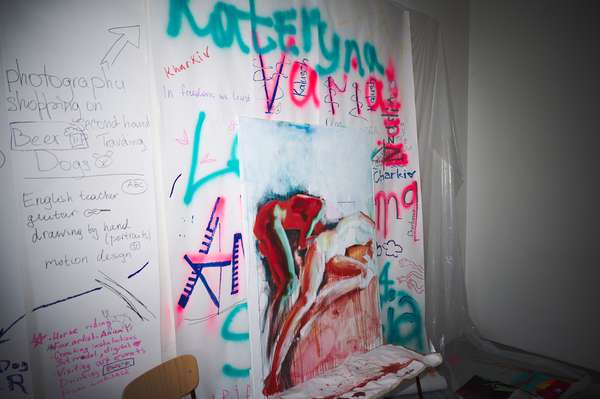

Art and war

Art and war

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

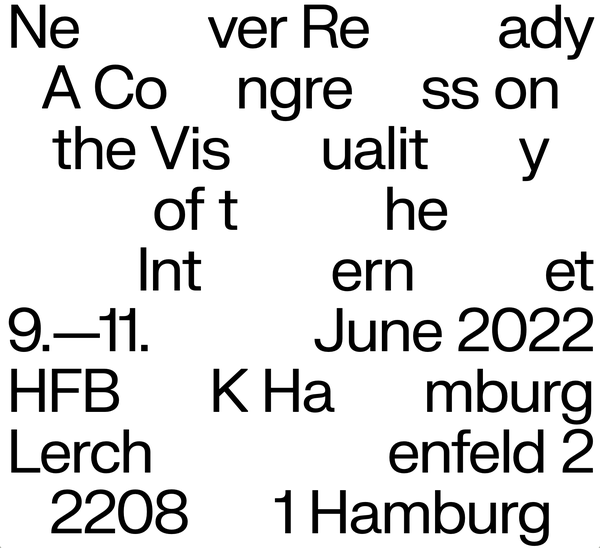

June is full of art and theory

June is full of art and theory

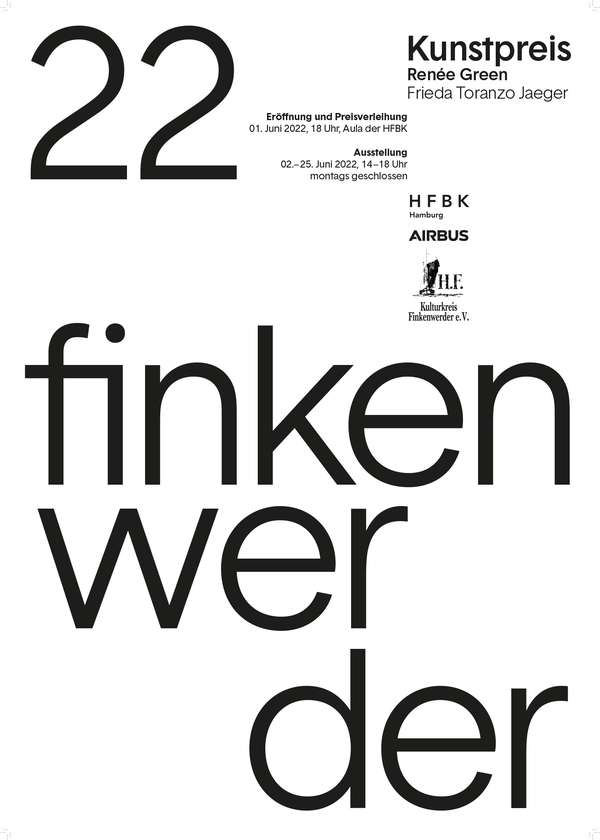

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2022

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2022

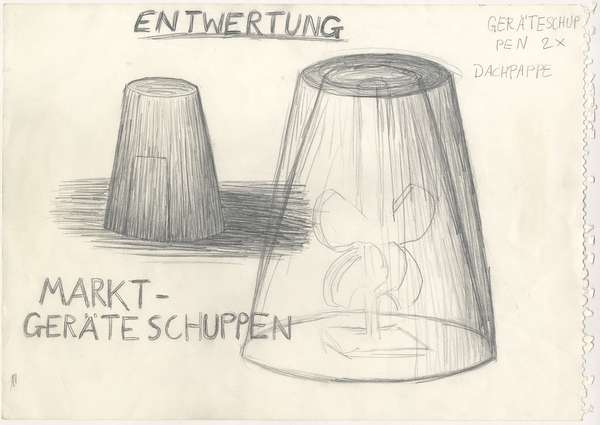

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Raum für die Kunst

Raum für die Kunst

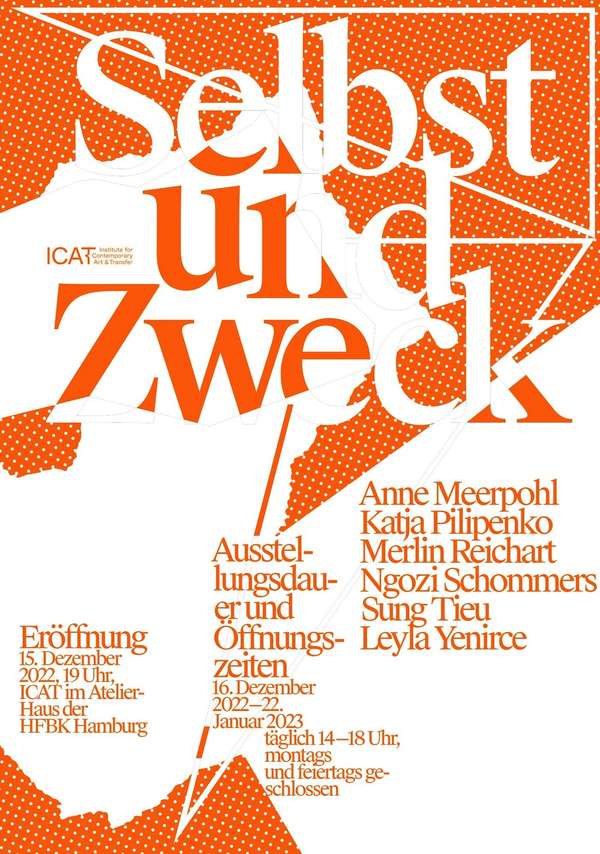

Annual Exhibition 2022 at the HFBK

Annual Exhibition 2022 at the HFBK

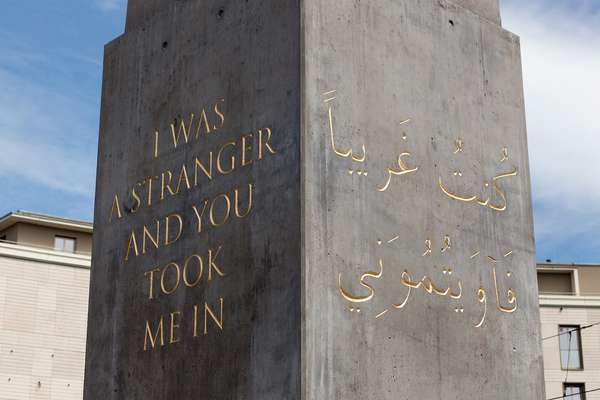

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments.

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments.

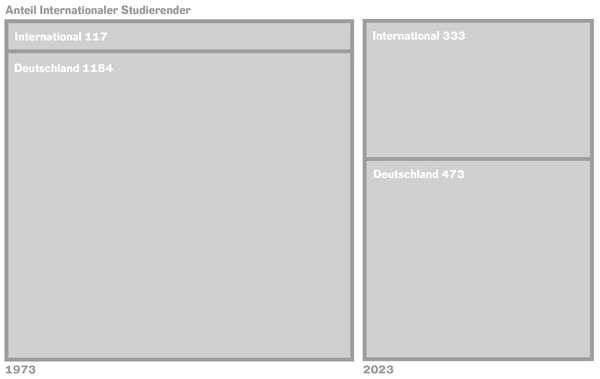

Diversity

Diversity

Summer Break

Summer Break

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

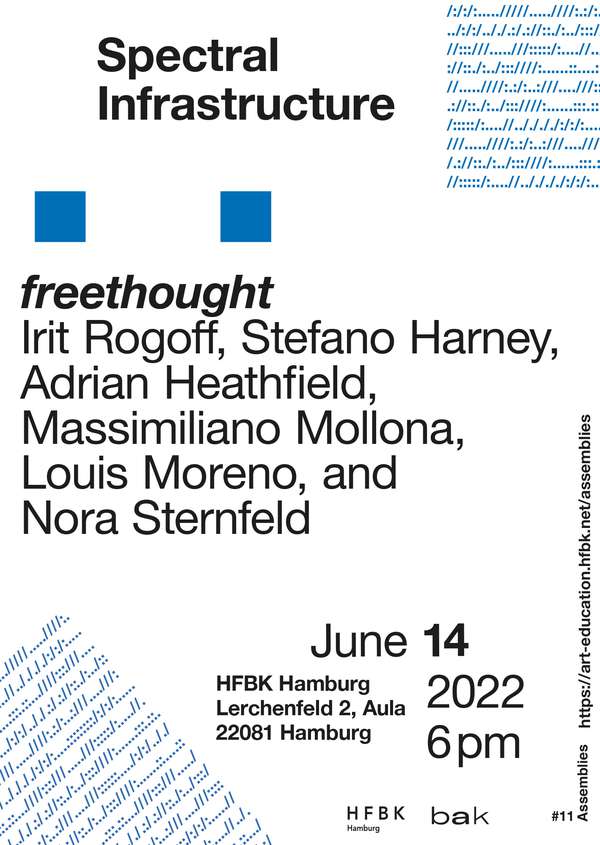

Unlearning: Wartenau Assemblies

Unlearning: Wartenau Assemblies

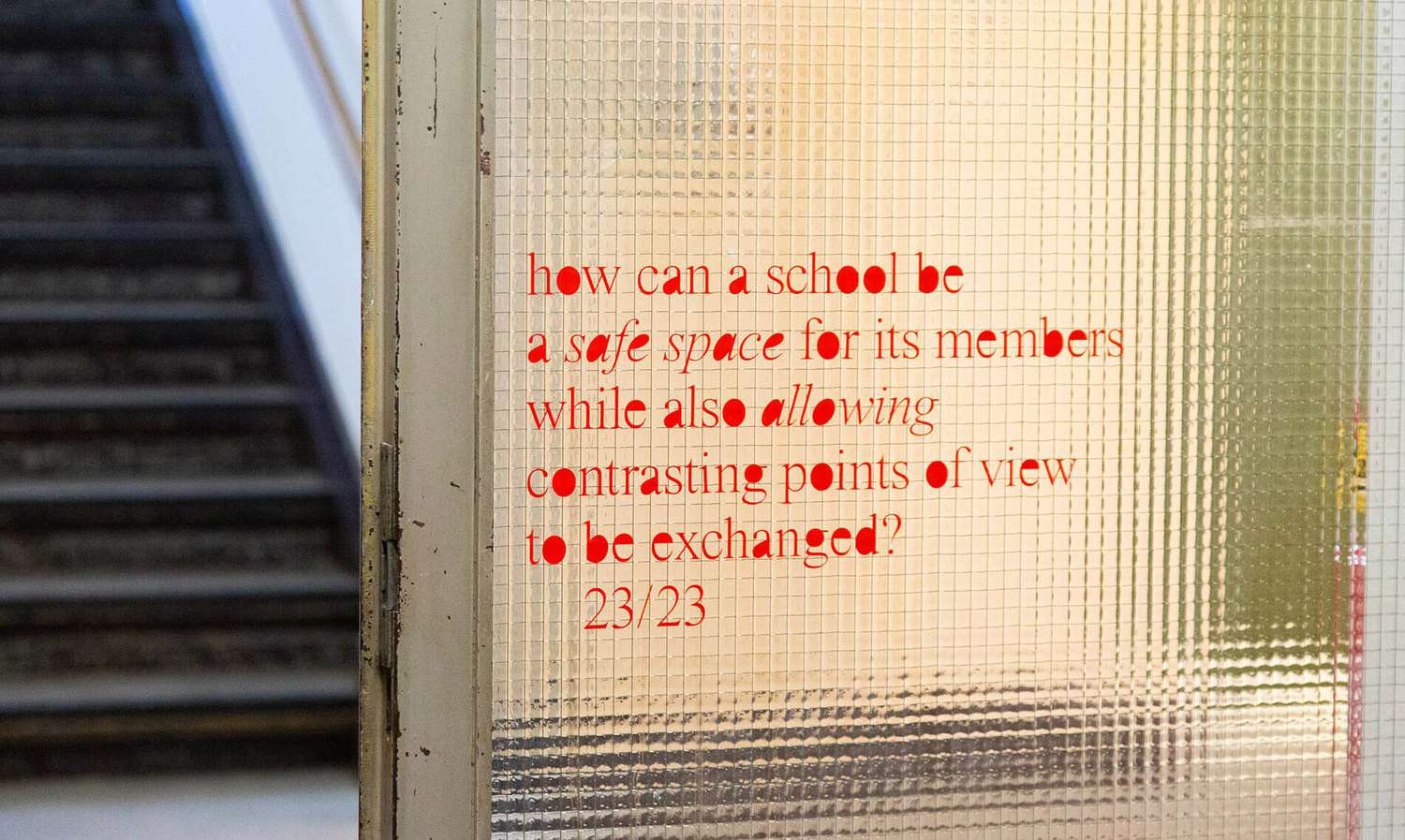

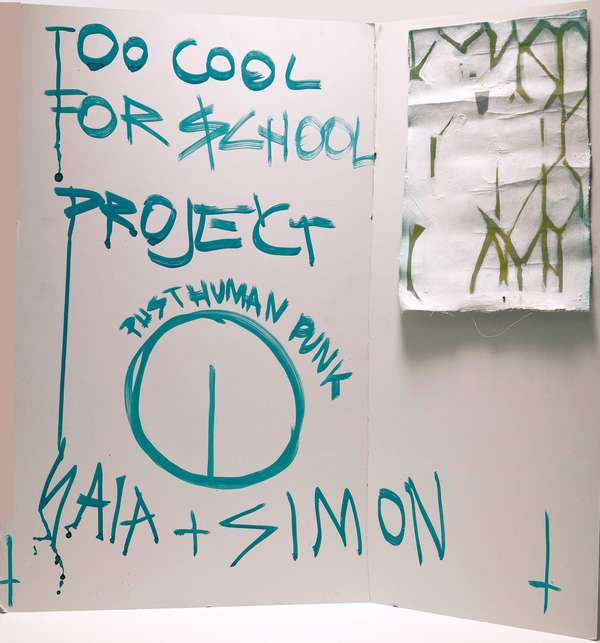

School of No Consequences

School of No Consequences

Annual Exhibition 2021 at the HFBK

Annual Exhibition 2021 at the HFBK

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

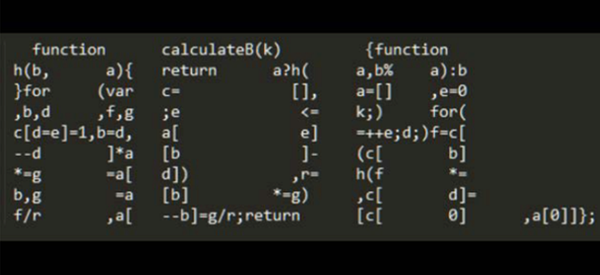

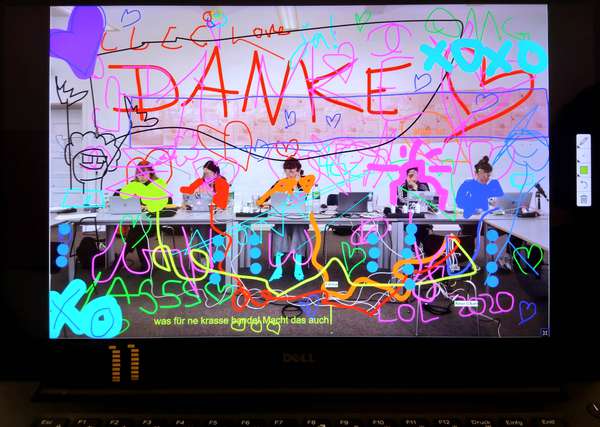

Teaching Art Online at the HFBK

Teaching Art Online at the HFBK

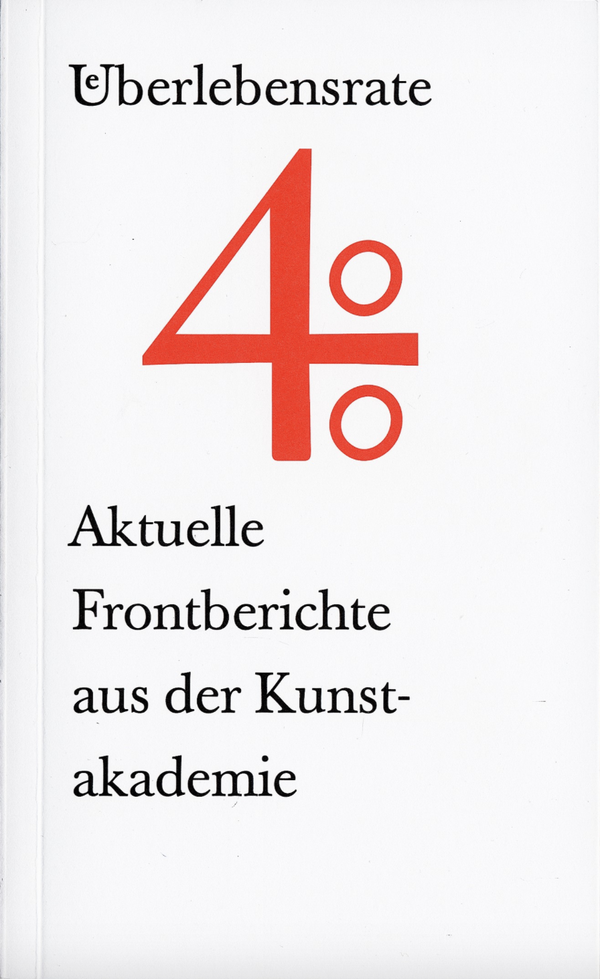

HFBK Graduate Survey

HFBK Graduate Survey

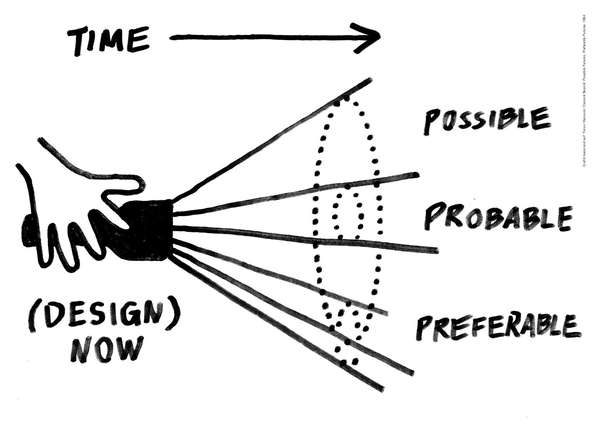

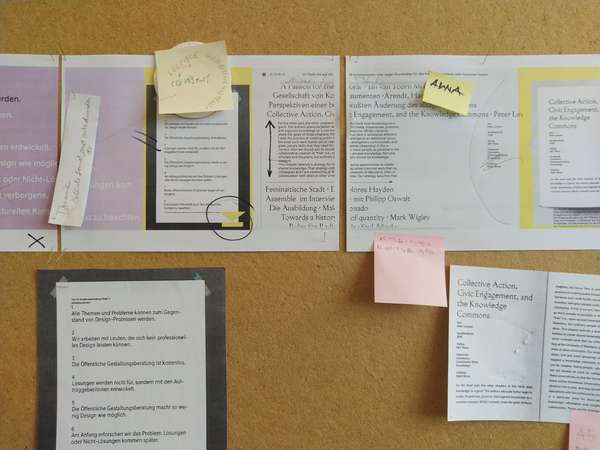

How political is Social Design?

How political is Social Design?