What do you actually do? – Astrid Kajsa Nylander

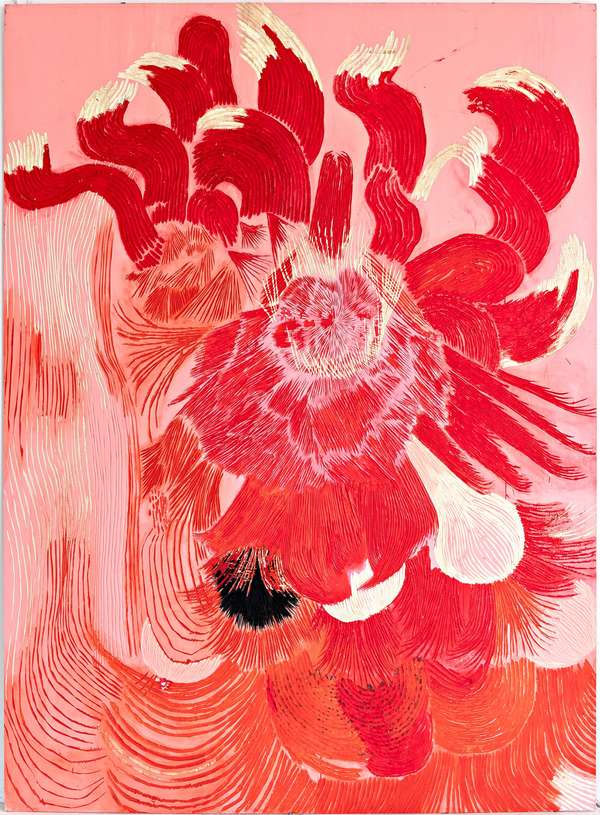

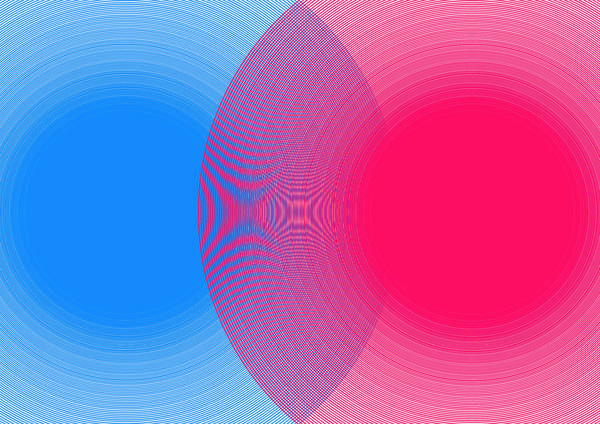

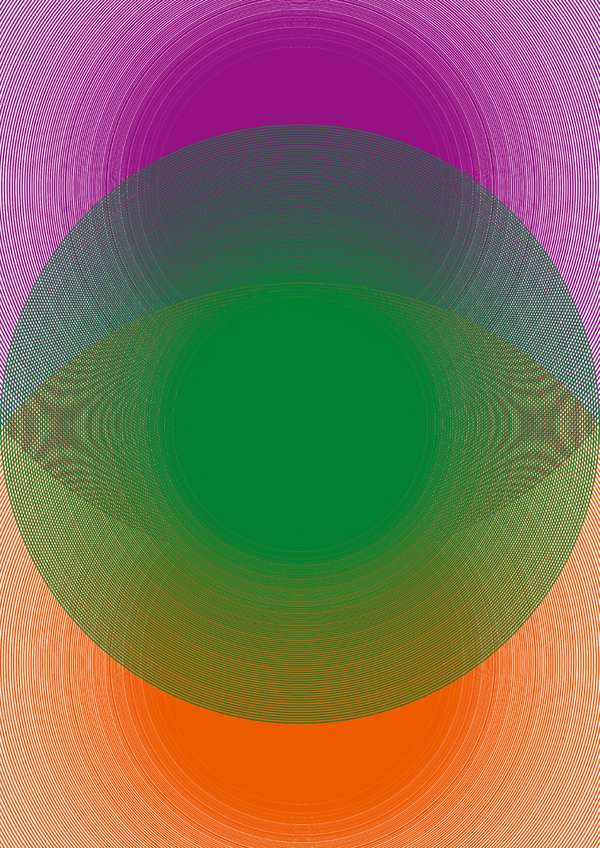

Astrid Kajsa Nylander may share her crowded Neukölln studio with two other artists, but it’s not difficult to spot which works belong to her. United by their vivid, almost garish colour combinations, Nylander’s painings stand out even in a room teeming with objects. “I was always very drawn to the idea of colour as a physical phenomenon,” she explains. “I want my paintings to be a space that the body reacts to.”

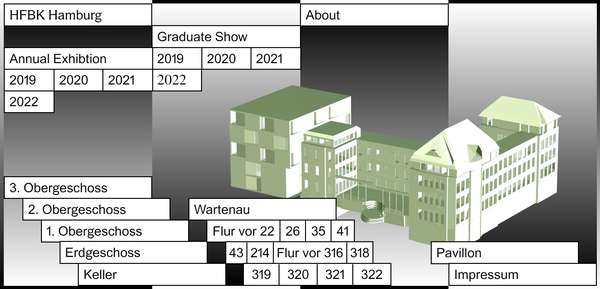

Born in Gothenburg, Sweden in 1989, Nylander cites the Gothenburg Colourists and the Skagen painters—two Scandinavian collectives active at the turn of the 20th century—as early influences on her colour palette. It’s easy to see why; known for their vibrant, light-filled canvases, both groups utilized colour as a tool to evoke emotion in their respective audiences. A less likely inspiration, Nylander tells me over tea and slices of cake, comes in the form of traffic signs. “When I was a teenager my hobby was to go out at night and steal them to put in my room,” she says with a laugh. “I thought they were the most amazing, beautiful things.” Nylander hasn’t always considered herself a painter. Starting her studies at the HFBK in the sculpture department, it was only during an exchange in the context of the Art School Alliance Program (ASA) at the San Francisco Art Institute that she began working on canvas. Based on a set of drawings Nylander made while she was still in Hamburg, her first painting series, minijobs, dates from this time. The series comprises images of buttons rendered in oil paint on shaped, sometimes pre-stretched canvases, an idea that suddenly came to Nylander during a trip to an art supplies shop. “I immediately had this ding moment of, yes, that’s how they should be,” she says.

The title of the series comes from both their diminutive size and the German concept of the “mini job,” a type of employment in which employees can only earn up to 450 euros, exempting them from paying income tax. Although the title came after she’d already started the paintings, Nylander’s buttons, which have looping painted “strings” that seemingly connect them to the canvas, could be seen as a metaphor for the lack of financial freedom that comes from these restricted roles. “You can’t make more money because then you get in trouble,” she says. “It’s a job that makes you dependent—you’re either relying on your family, your partner, or undeclared income.”

There is also a gendered aspect to this. As critic Francesca Lacatena pointed out in her 2019 essay on the minijobs series, last year two thirds of “mini-jobers” were women. “This special status,” she wrote, “was originally justified by the supposed limited labor market attachment of the country’s married women whose role in the traditional family model was at best that of supplementary income earner.”

It bears repeating that women, alongside the myriad of other challenges they face, are still paid 80 cents for every dollar a man earns (for women of colour this statistic is even worse). As a female artist, Nylander has tried to combat the current system—“which is basically working against you”—by collectivizing. While still a student she was a member of the Hamburg-based feminist collective CALL. After graduation she moved to Berlin to take part in Goldrausch, a program for female artists offering 15 women per year workshops in professional development in an attempt to combat the most frequent challenges faced by female artists. “I think it’s important to be with other female artists in a group to share questions, dreams, and insecurities,” explains Nylander. “It’s pointless to try and solve these problems alone.”

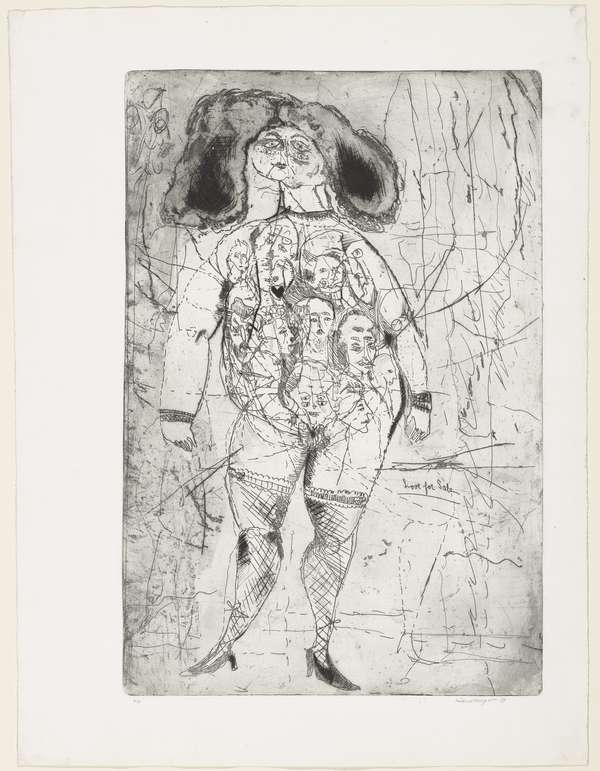

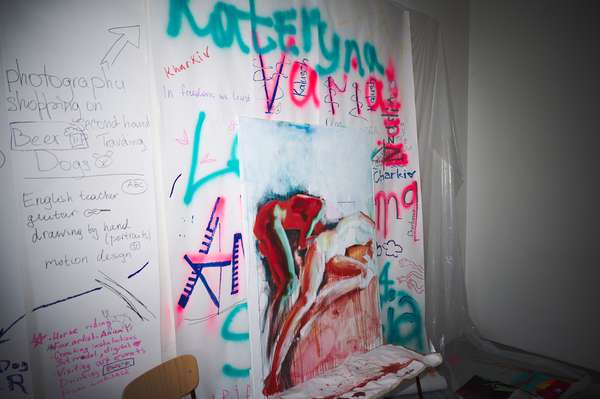

For her latest series, these interests found their way onto her canvases. Based on protest signs from the 2017 Women’s March, the series began out of an interest in the allure of the analogue in our digital age. “We do everything on a computer now,” Nylander explains, “but it occurred to me during the protests that when we go out in the streets we're still taking paint and making these often quite personalized posters.” As with the minijobs series, many of these pieces exist somewhere between objects and paintings—they function as, and are representations of, signs of protest. “In the beginning,” Nylander continues, “I was wondering how I could actually transform these signs into paintings. Then I came to the idea that it would actually be interesting to just paint them as they are—like a study.”

At her recent solo exhibition at the Kunstverein Siegen, Nylander showed these “studies” alongside a large-scale painting featuring further images of posters from the protest with flowers that are growing in and around fences. “I see this as a symbol for the patriarchy,” she explains of this inclusion. “It's not us versus the patriarchy because we're actually intertwined,” she says. “The question is, how can you protest against something that you grew up within?” Taken from the blurb on the back of a hairspray bottle, the exhibition title, Mega Widerstandskraft (mega resistance), further underlines this point. The absurdity of the language of political resistance being repackaged and used to sell beauty products is not lost on Nylander. As she puts it, “I mean, what has the firmness of your hair got to do with it?”

Astrid Kajsa Nylander studied at the HFBK Hamburg from 2012-18 with Jutta Koether and Hanne Loreck. In 2019, she had a solo show at Kunstverein Siegen and took part in group shows at Crum Heaven, Stockholm; MiART, Milan; Gallery NTK, Prague; Strizzi Space, Cologne; and Haus am Kleistpark, Berlin. She is currently based between Stockholm and Berlin.

More information: http://astridkajsanylander.net/

HFBK graduate Chloe Stead, together with the photographer and also HFBK graduate Jens Franke, met former HFBK students to talk about work, life and art. It is the prelude to a series of interviews for the website of HFBK Hamburg.

Autumn program for everyone

Autumn program for everyone

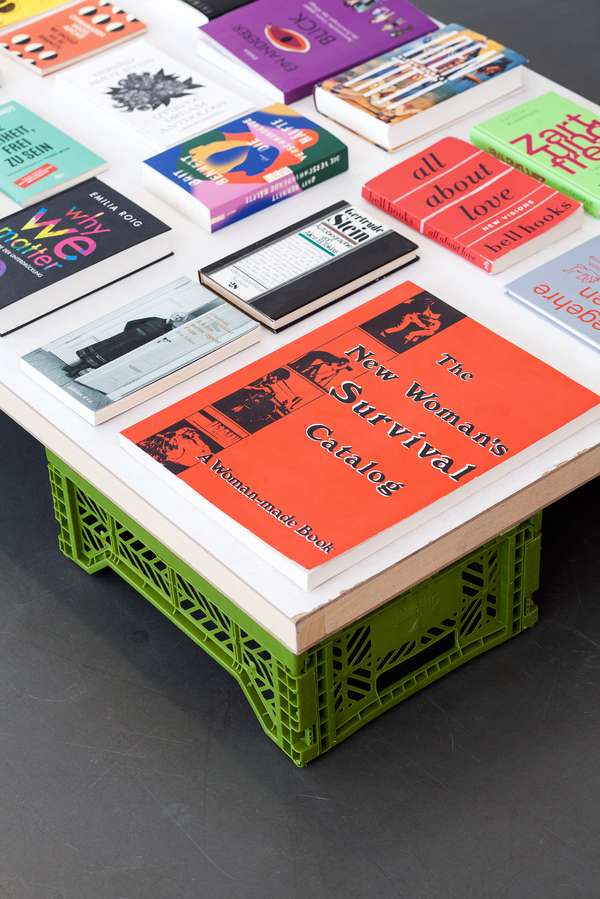

The New Woman

The New Woman

Opening of the 2024/25 semester centred on the new film house

Opening of the 2024/25 semester centred on the new film house

Doing a PhD at the HFBK Hamburg

Doing a PhD at the HFBK Hamburg

Summer of theory

Summer of theory

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2024

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2024

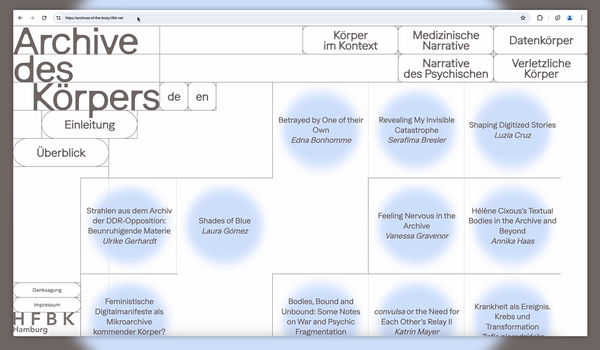

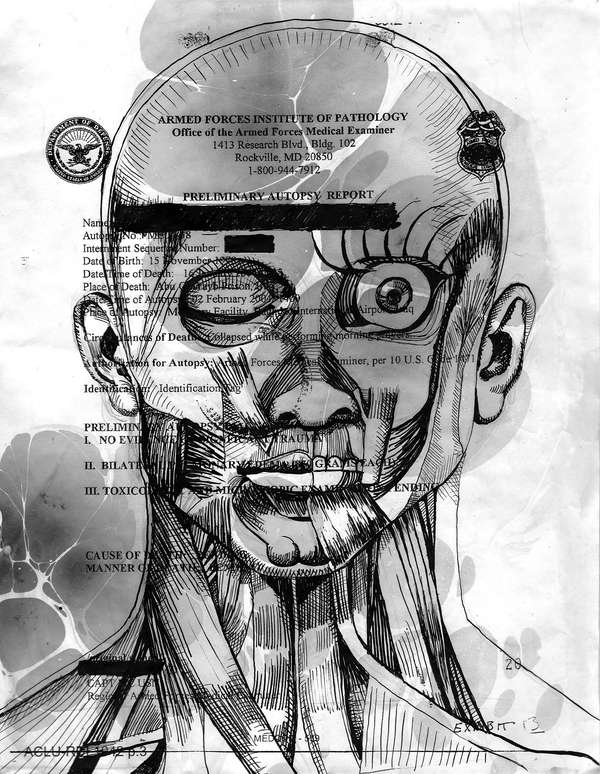

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

New partnership with the School of Arts at the University of Haifa

New partnership with the School of Arts at the University of Haifa

Exhibition recommendations

Exhibition recommendations

Annual Exhibition 2024 at the HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2024 at the HFBK Hamburg

How to apply: study at HFBK Hamburg

How to apply: study at HFBK Hamburg

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

Extended Libraries

Extended Libraries

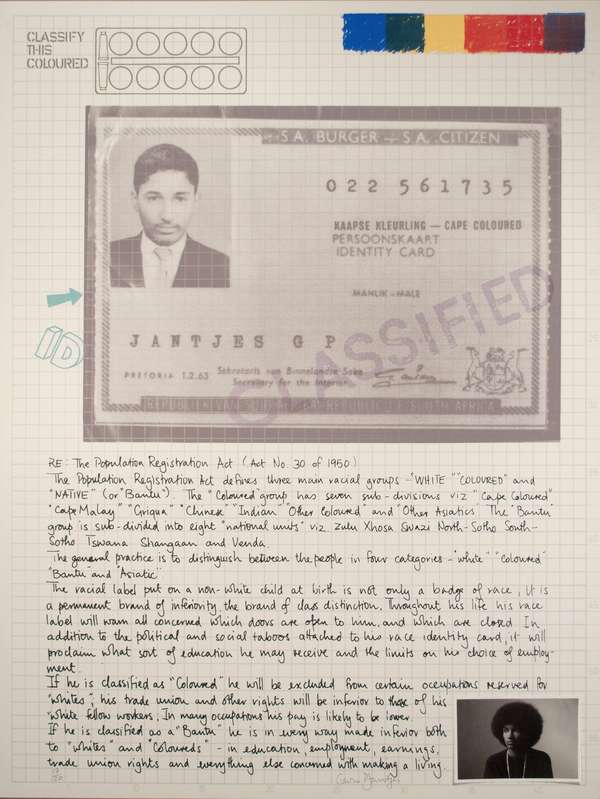

And Still I Rise

And Still I Rise

No Tracking. No Paywall.

No Tracking. No Paywall.

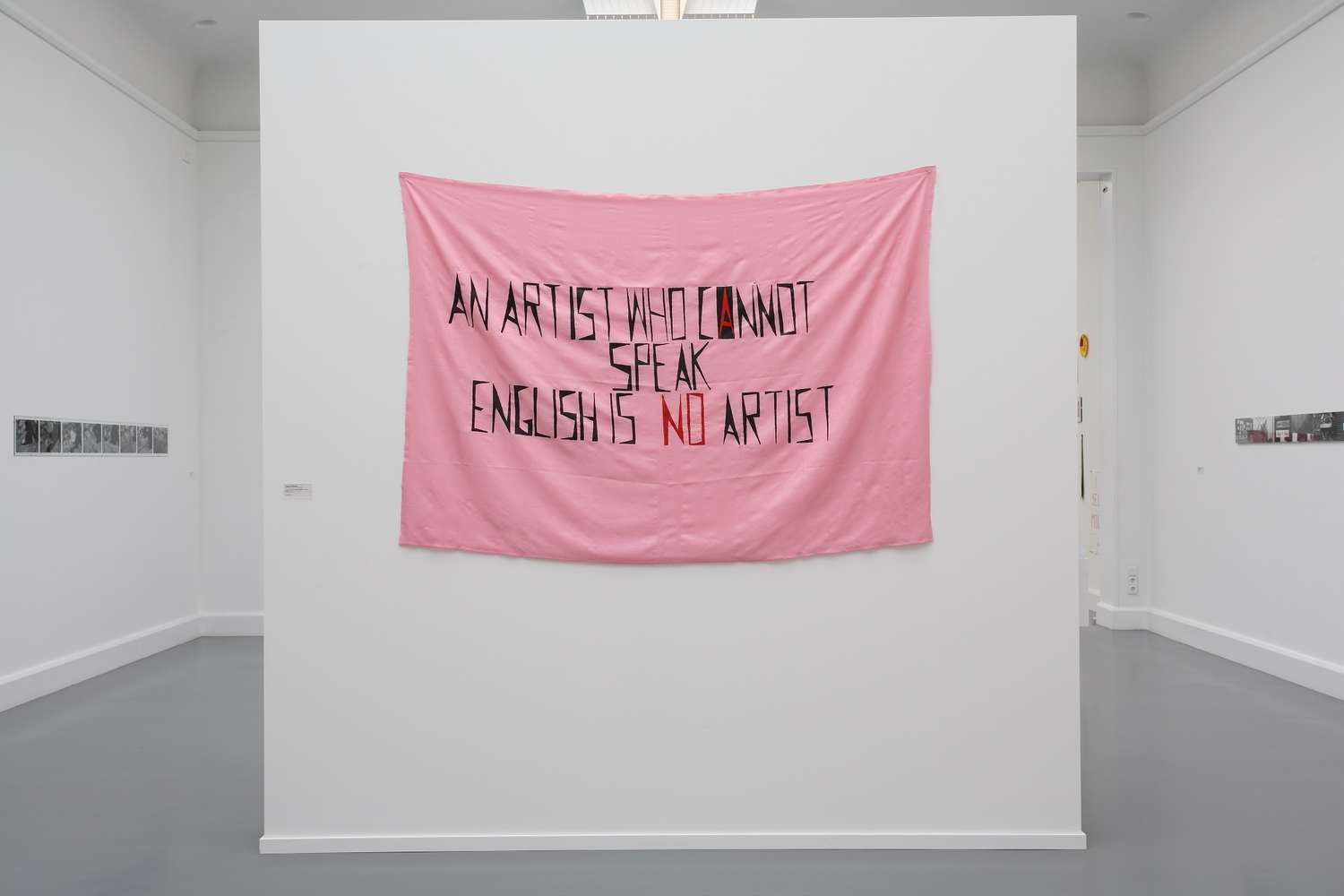

Let's talk about language

Let's talk about language

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

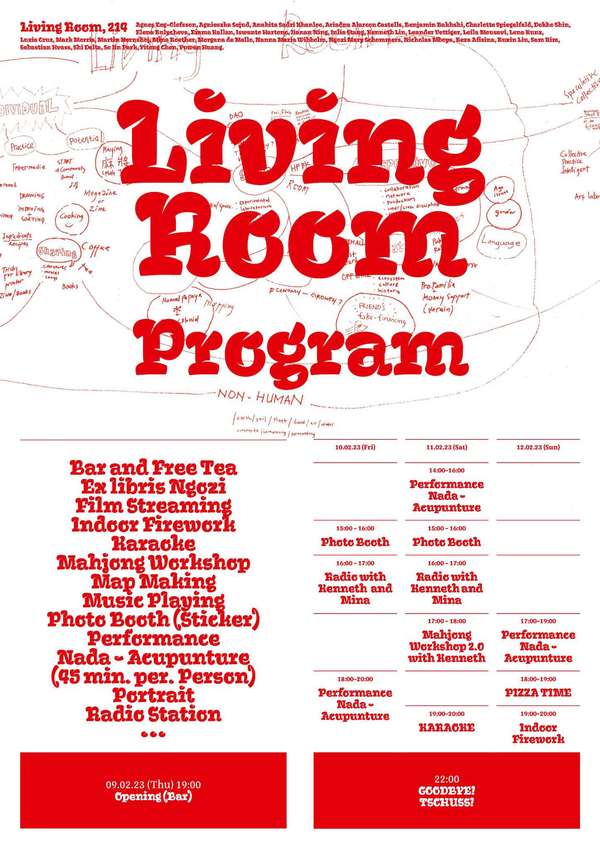

Let`s work together

Let`s work together

Annual Exhibition 2023 at HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2023 at HFBK Hamburg

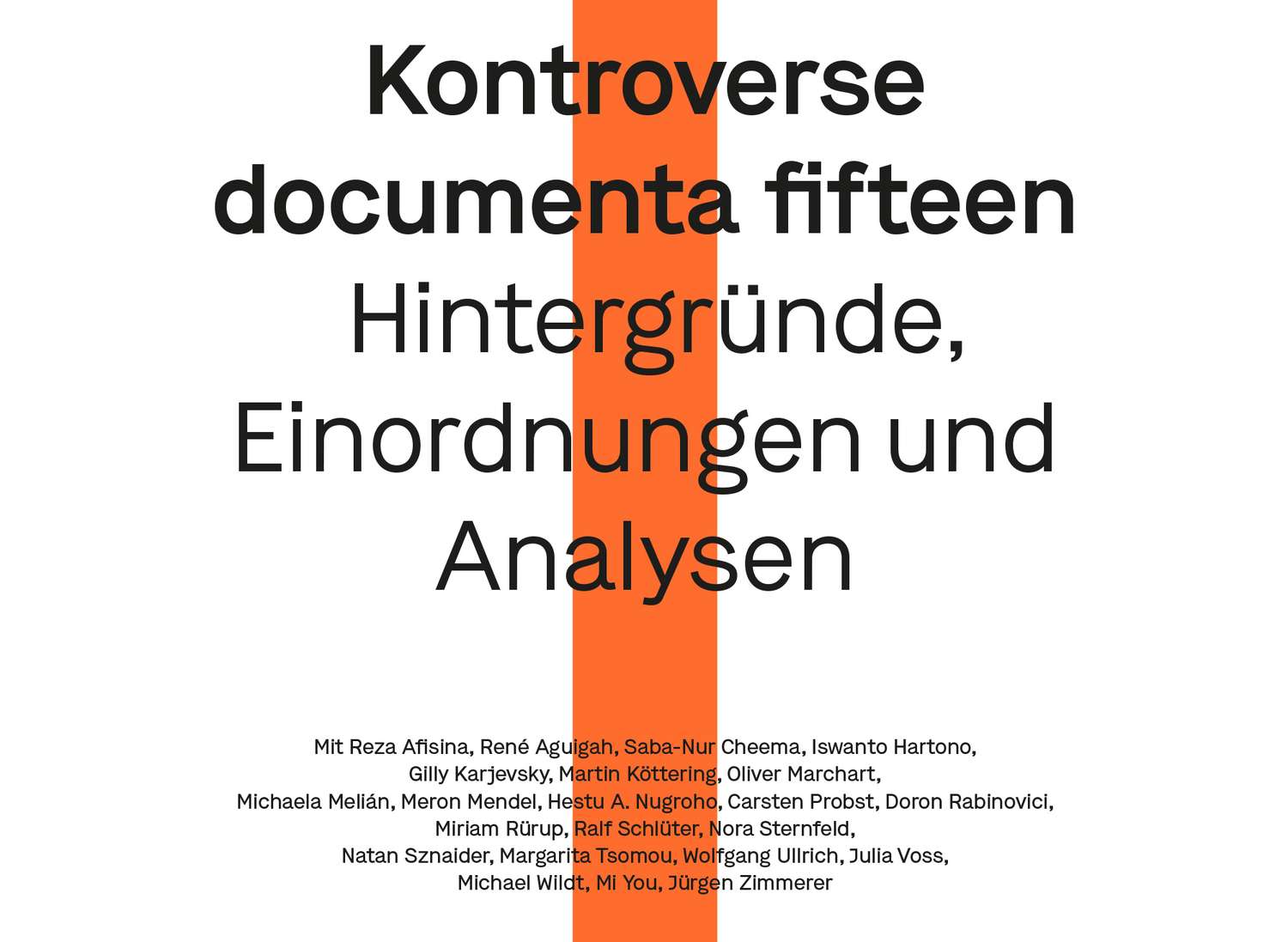

Symposium: Controversy over documenta fifteen

Symposium: Controversy over documenta fifteen

The best is saved until last

The best is saved until last

Festival and Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

Festival and Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

Solo exhibition by Konstantin Grcic

Solo exhibition by Konstantin Grcic

Art and war

Art and war

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

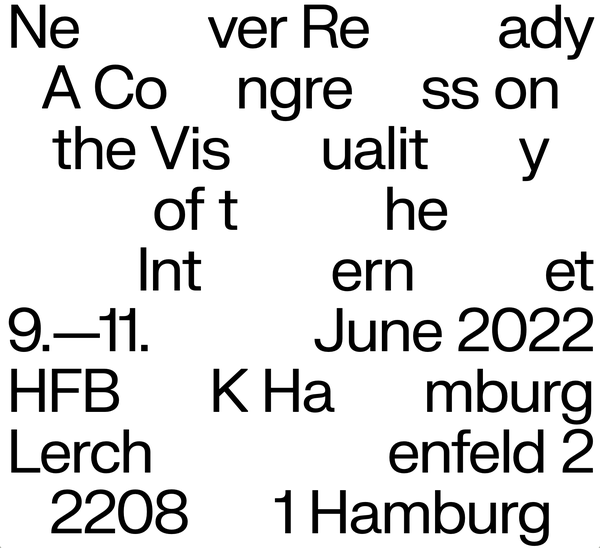

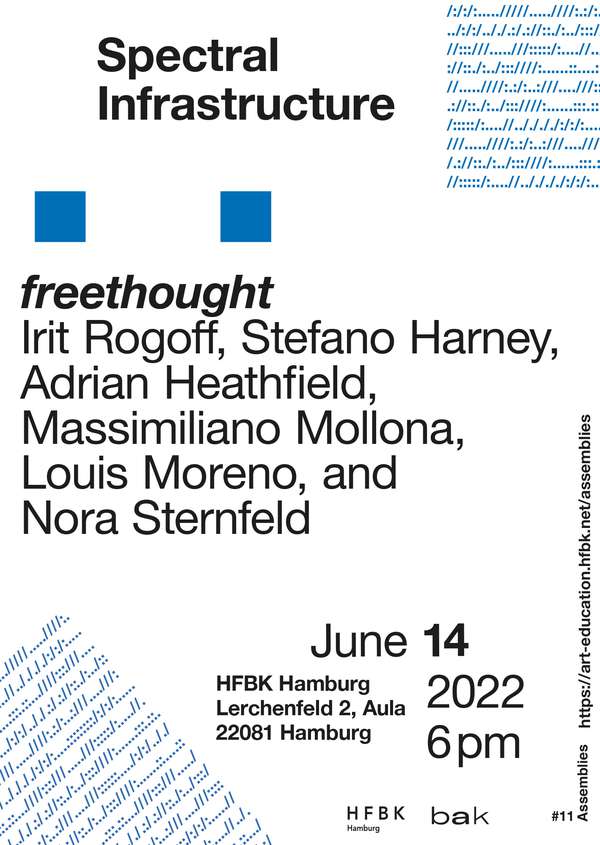

June is full of art and theory

June is full of art and theory

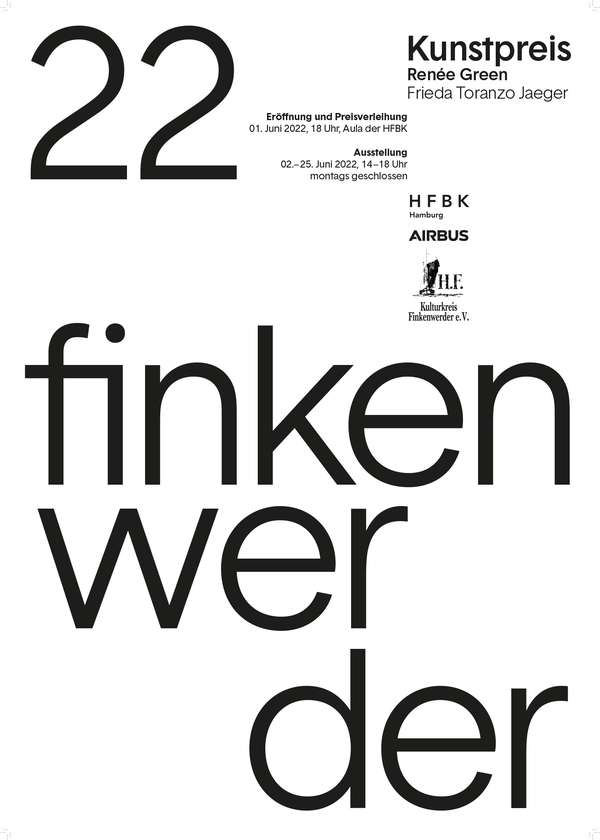

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2022

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2022

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

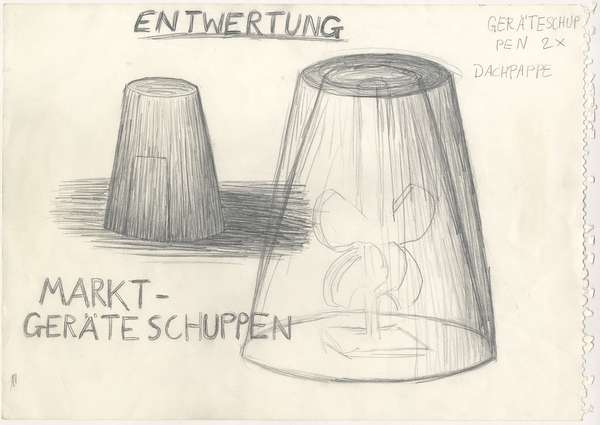

Raum für die Kunst

Raum für die Kunst

Annual Exhibition 2022 at the HFBK

Annual Exhibition 2022 at the HFBK

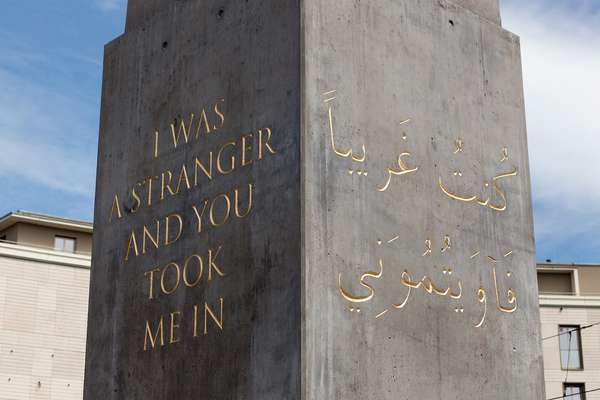

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments.

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments.

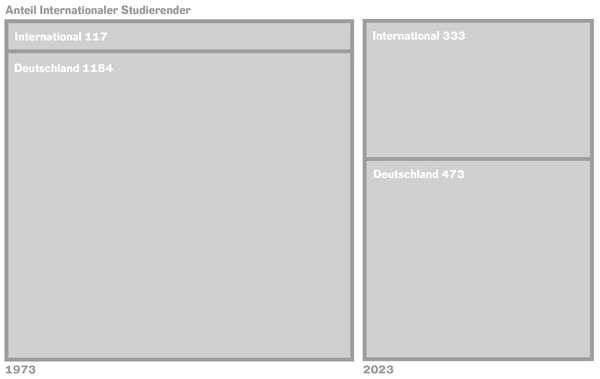

Diversity

Diversity

Summer Break

Summer Break

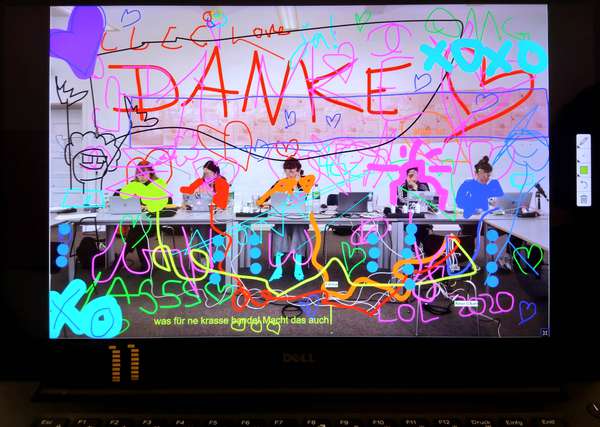

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

Unlearning: Wartenau Assemblies

Unlearning: Wartenau Assemblies

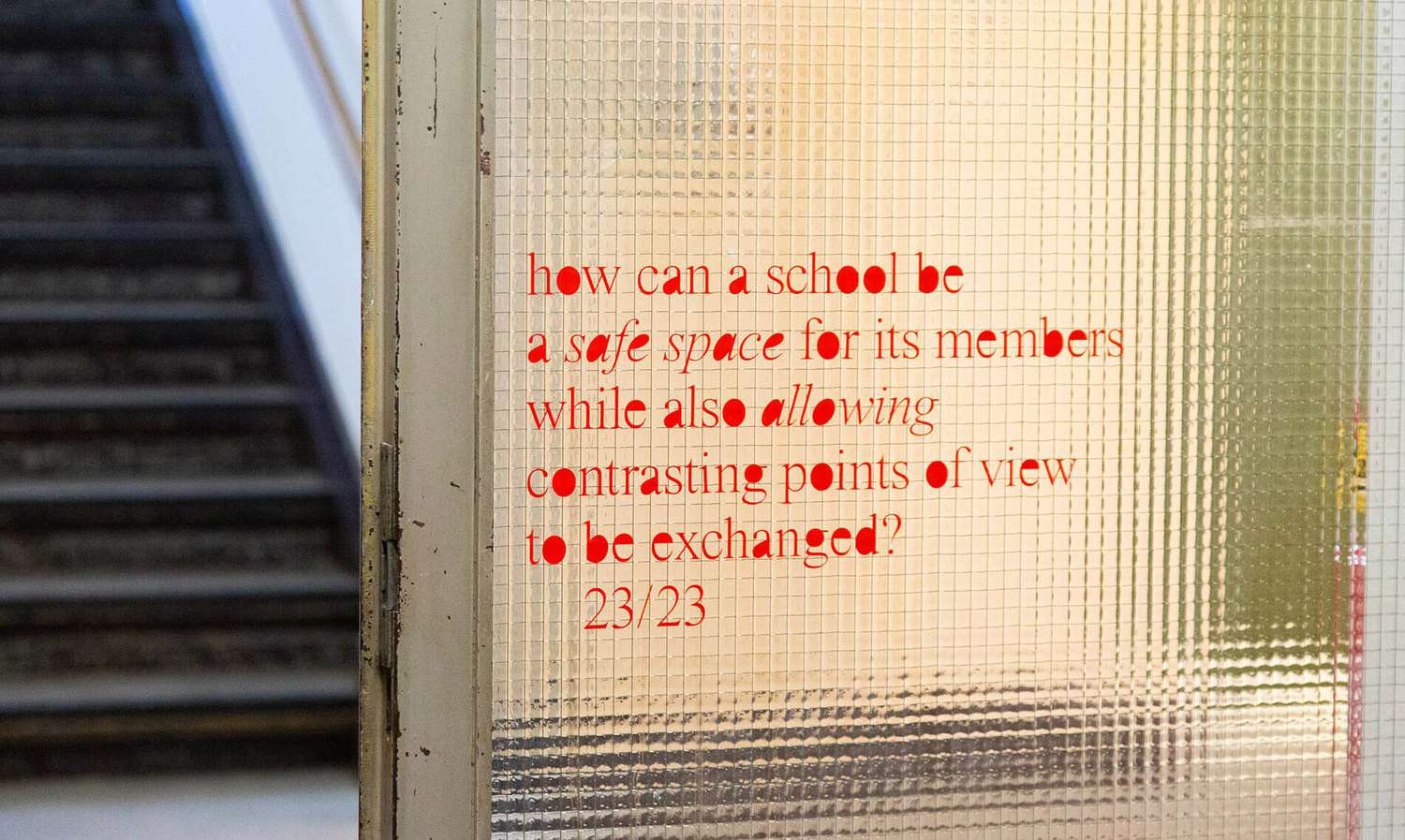

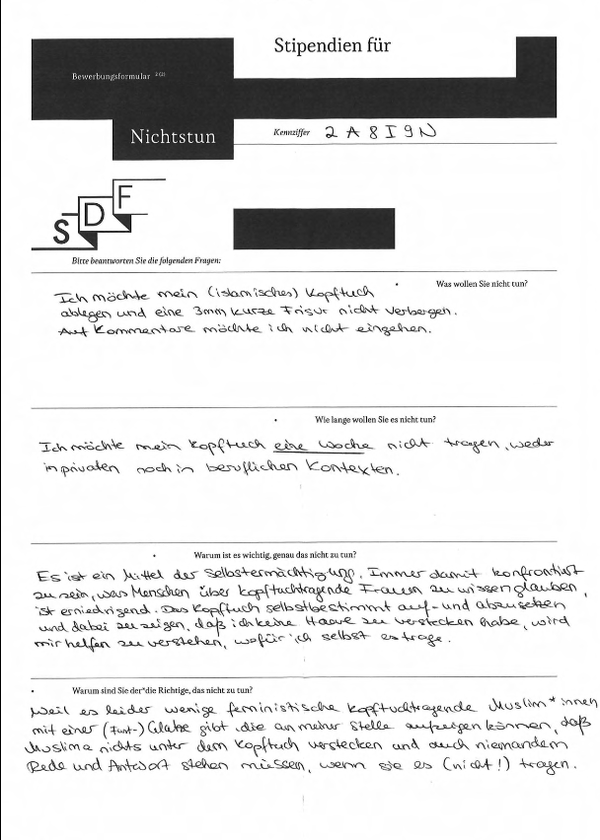

School of No Consequences

School of No Consequences

Annual Exhibition 2021 at the HFBK

Annual Exhibition 2021 at the HFBK

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

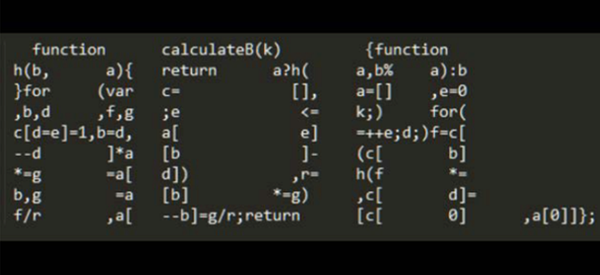

Teaching Art Online at the HFBK

Teaching Art Online at the HFBK

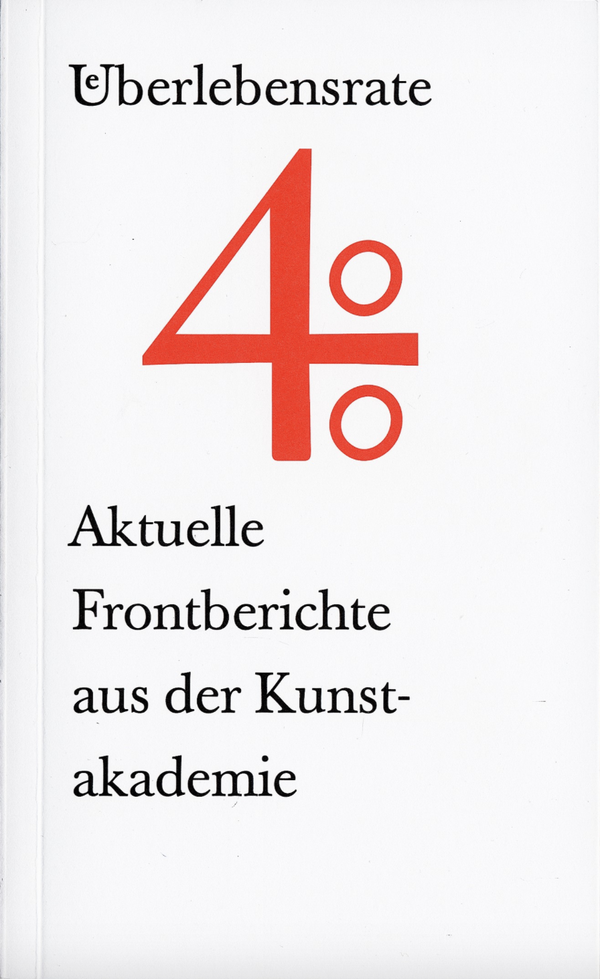

HFBK Graduate Survey

HFBK Graduate Survey

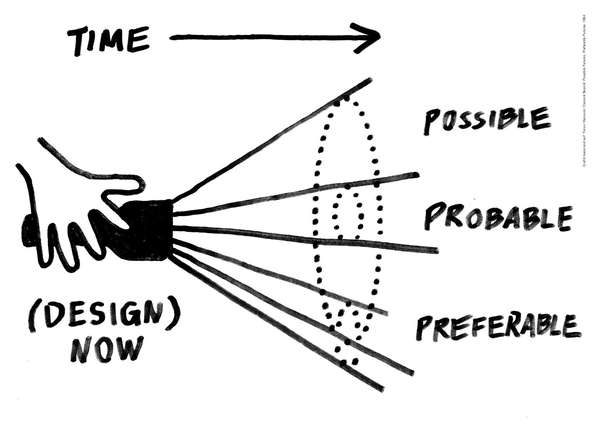

How political is Social Design?

How political is Social Design?